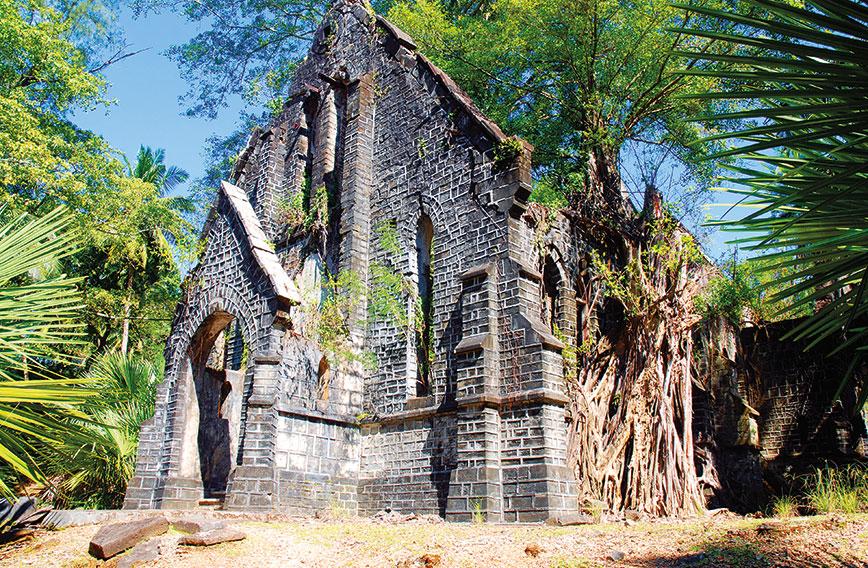

The Presbyterian church now covered with foliage

At Ross Island a bakery, club house from its past

Susheela Nair , Port Blair

From the Phoenix Boat Jetty in Port Blair, a boat ferried us to Ross Island, the erstwhile administrative capital of the British in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. The island conjured up gory visions of the dreaded ‘Kalapani’ punishment meted out to convicts by the British in pre-Independence India. A penal settlement was established on Ross Island where political prisoners and freedom fighters were thrown into the same cells as hardcore criminals.

One could imagine the times when chained prisoners were compelled to perform hard menial labour. Some committed suicide due to the inhuman treatment meted out to them by the then superintendent. Escorting us around, our guide explained that convicts were left out in the open under the trees with the dark sea and sky for company. That’s why the island was known as ‘Kalapani’ or black water.

Ross Island has an illustrious history. It lost some of its prominence after the Cellular Jail came up in Port Blair but continued to be a centre of British power until the Japanese occupied it in 1942 during the Second World War. When the Japanese forces vacated Ross Island in 1945, it was reoccupied by the British and the penal settlement was abolished. The island suffered during the Japanese occupation and also the earthquake of 1942. It served as the capital of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands from1858 until 1941, the year the Japanese occupied it and converted it into a POW site. Subsequently, the Indian Navy took over the island. Currently, known for its gruesome history, it has landscaped paths across the island and most of its buildings are labelled.

Ross Island was once British India’s sentinel in the Bay of Bengal, originally developed as the residence of the chief commissioner. It is named after Captain Daniel Ross who was the marine surveyor of the Indian Navy from 1825 to 1840. At the entrance, I saw concrete bunkers, a legacy of the Japanese. Crumbling buildings and a jumbled tropical forest are what greet visitors. I spotted chital and peacocks amidst the foliage and a few darted across our path. They were introduced to these islands almost a century ago by Sir Henry Farrington, a forester.

Ross Island was once British India’s sentinel in the Bay of Bengal, originally developed as the residence of the chief commissioner. It is named after Captain Daniel Ross who was the marine surveyor of the Indian Navy from 1825 to 1840. At the entrance, I saw concrete bunkers, a legacy of the Japanese. Crumbling buildings and a jumbled tropical forest are what greet visitors. I spotted chital and peacocks amidst the foliage and a few darted across our path. They were introduced to these islands almost a century ago by Sir Henry Farrington, a forester.

Roaming around the island turned out to be a voyage of discovery. I was transported into a strange world of ramshackle edifices overtaken by dense tropical foliage. It was difficult to spot a single undamaged structure on this 200-acre island. Every building supported a huge tree, the roots forming intricate patterns on the walls. The remnants of an opulent past can be seen in the ruins of the bazaar, stores, water treatment plant, secretariat, hospital, cemetery and other structures. A few small black boards with signs like ‘Printing Press’, ‘Barracks’, ‘Club’ indicated what the buildings had originally served as. Huge boilers were lying rusting in the spray of the sea, the roof of the laundry had fallen in and the walls of a shop run by an Indian were covered with the roots of untamed trees.

A coconut palm grove occupies the once fashionable tennis court, adjacent to the ‘Club’. I saw small black boards along the footpath indicating the long gone landmarks. I chanced upon a derelict building labelled ‘Club House’ and then a swimming pool area, now all covered with moss, weeds and undergrowth. You can distinctly make out the ballrooms and the swimming pools. The renovated ‘Bakery’ once used to offer loaves, buns, cakes, croissants and many other delicacies of those times.

A coconut palm grove occupies the once fashionable tennis court, adjacent to the ‘Club’. I saw small black boards along the footpath indicating the long gone landmarks. I chanced upon a derelict building labelled ‘Club House’ and then a swimming pool area, now all covered with moss, weeds and undergrowth. You can distinctly make out the ballrooms and the swimming pools. The renovated ‘Bakery’ once used to offer loaves, buns, cakes, croissants and many other delicacies of those times.

Strolling around the island, I discovered that even in the early 19th century the British knew how to live life well. A winding path and steps led us to the old hospital and the barracks, the churches, residences, gardens, the officers’ club and the non-commissioned officers’ mess. I could see the last vestiges of imperial grandeur in the Italian tiled courtyard within the dilapidated Chief Commissioner’s Residence which was patterned on Windsor Castle. The British enjoyed a vibrant social life here with parties, dances, tennis matches, cricket and other activities. In its heyday, Ross Island was fondly called the Paris of the East. But British revelry ended on this island when it was hit by an earthquake in 1941. They then abandoned Ross Island as a residential hub and shifted to Port Blair.

The ruins of the church and the chief commissioner’s house amidst overgrowing vines and aerial roots are among the most evocative of the ruins. South of the commissioner’s house on a hilltop stand the crumbling remains of an Anglican church, which has survived the onslaught of tropical creepers and vines. This Presbyterian church was built of stone and the windows had frames made of Burma teak. The glass panes behind the altar were made of beautifully etched stained glass from Italy. The quality of the wood was so superior that it survived the vagaries of the weather for over 100 years. A small structure, south of the church, was built to accommodate the parsonage. Some of the grave sites are still visible, haunted with memories.

The ruins of the church and the chief commissioner’s house amidst overgrowing vines and aerial roots are among the most evocative of the ruins. South of the commissioner’s house on a hilltop stand the crumbling remains of an Anglican church, which has survived the onslaught of tropical creepers and vines. This Presbyterian church was built of stone and the windows had frames made of Burma teak. The glass panes behind the altar were made of beautifully etched stained glass from Italy. The quality of the wood was so superior that it survived the vagaries of the weather for over 100 years. A small structure, south of the church, was built to accommodate the parsonage. Some of the grave sites are still visible, haunted with memories.

The island is officially still under the jurisdiction of the Indian Navy. A small museum of the Navy, Smritika, has a good collection of old records and brings alive the past of this hoary island. The small museum by the cafeteria has interesting

old photos.

Fact File

Fact File

Getting there: Ross Island is open from dawn to dusk, except on Wednesdays. There are ferry services from Phoenix Bay. There is a sound and light show depicting the history of the island at 5:30 pm. The ticket is inclusive of the boat ride, entry fee to Ross Island and the show charges. Tickets are available at the Directorate of Tourism office.