The Ghazipur mountain of garbage

Getting rid of a garbage mountain

Civil Society News, New Delhi

A mountain of garbage, now 65 metres high and roughly as tall as the Qutub Minar, looms as a major civic embarrassment over Delhi.

Located at the Ghazipur landfill in the frayed eastern fringes of the capital, the garbage mountain has been in the making over the past three decades.

Getting rid of this fetid legacy now could take as long as 10 years — and that, too, if there is an innovative and well-managed effort led by the state government and municipal authorities.

Some efforts are underway, but in the meantime new waste is also being dumped around the mountain. There are an estimated 2,000 tonnes turning up every day at Ghazipur from within the east Delhi area. So, even if the mountain is got rid of, it will not necessarily mean the end of the dump.

A garbage mountain festering in full view is a major embarrassment for a capital city. But Delhi, like almost all other Indian cities, shoves its solid waste out of sight only to find itself in its menacing shadow over time. Apart from Ghazipur there are two other overflowing landfills at Okhla and Bhalasawa. Delhi generates about 12,000 tonnes of garbage per day.

When the Test cricketer, Gautam Gambhir, got elected to Parliament from the East Delhi seat as a BJP candidate in 2019, one of the promises he made was that the mess at Ghazipur (it falls in his constituency) would be cleaned up by the end of 2024, when his term ends and he would need to stand for election again.

It is not going to be easily done. If election promises could make garbage disappear, India’s cities would be much cleaner. A whole lot more is needed.

To be fair to Gambhir, he has acted. The East Delhi Municipal Corporation (EDMC), which is run by the BJP, has been mining the garbage at Ghazipur. In fact, Gambhir claims the height of the mountain has come down by a few feet or so. But much hard work lies ahead.

|

|

Raj Kumar of Zonta Infratech |

How can a garbage mountain be removed? It is a managerial challenge, we are told by Raj Kumar, MD and CEO of Zonta Infratech, a company that provides cities with waste management systems.

A city government which wants to seriously deal with its waste must be prepared to introduce innovative policies and take entrepreneurial decisions. It must be ready to build a system in which the garbage problem is addressed in homes and commercial establishments with segregation of biodegradable and recyclable waste.

How soon a mountain of legacy garbage can be made to vanish will depend on a government’s savvy. Garbage can be incinerated, turned into biogas, recycled and buried.

To exercise such options several moves have to be made. Among them is the incentivizing of large industrial users to put the garbage to alternative use such as burning it for energy.

“Before biomining waste, you have to decide what you want to do with it,” says Kumar, who has been involved in getting rid of garbage mountains in Tirunelveli and Jabalpur. He has also been looking at best practices all over the world.

“The term ‘mining’ in itself implies that there is a raw material. The question is who has use for it? To which industry should it go?” he explains.

One big user of garbage is the cement industry where the garbage becomes RDF or refuse derived fuel. Garbage in Ghazipur could end up in the clinkers of cement factories where it would be burnt for energy.

One big user of garbage is the cement industry where the garbage becomes RDF or refuse derived fuel. Garbage in Ghazipur could end up in the clinkers of cement factories where it would be burnt for energy.

But cement plants are not necessarily located close to garbage dumps and certainly not the one at Ghazipur. There would be transportation costs in sending the garbage to distant factories which the government would have to bear. Then again, cement factories need garbage in which the moisture is within certain limits.

One cannot also depend entirely on the cement industry. It is necessary to have other options. For instance, waste-to-energy plants can be relied upon to be large and continuous consumers of garbage.

The EDMC’s initiative in Ghazipur could do with a more robust and realistic strategy for reducing a garbage mountain of the size that exists there. It needs bigger consumers with incentives thrown in so that not only does the mountain come down quickly but the daily addition of 2,000 tonnes or so is dealt with.

Currently, about 15 percent of the waste mined in Ghazipur is sent to waste-to-energy plants located there. Around 20 percent is used for making bricks and tiles at the construction and demolition plants of the EDMC. Good earth from the dump, which accounts for 50 percent of the waste, goes to the National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC)’s eco-park in Delhi and the EDMC’s parks. The EDMC is reportedly mining 3,000 tonnes a day.

Delhi has three waste-to-energy plants. It is hardly enough. In fact, India on the whole has five plants and with those that are coming up the number could be eight or nine.

In India these plants are mired in controversy. Governments have problems finding locations for them because of objections raised by local communities. There are also activists who have taken up cudgels against them, denouncing them as polluting. One view is that the composition of Indian garbage is not suitable for incineration.

Not everyone would agree. Kumar points out that China has around 500 waste-to-energy plants running successfully. The parallel is important because the composition of China’s waste is not dissimilar from waste in India.

In fact, the world over, cities that have cleaned up their waste have relied on turning it into energy. Pollution from their plants has been neutralized through the use of better technologies.

Biomining of garbage is done using large trommels to which there are magnetic attachments and screens and sieves. Depending on the nature of the waste it can be put to different uses.

There are three or four categories of waste. The first is the kind that can be incinerated. It can provide refuse derived fuel and can go into the clinkers of cement factories or can be used in waste-to-power plants.

The second is good earth, soil or sand which can be used for filling low-lying areas or during road-making. A third fraction consists of rocks, small stones and dust which have no uses and can be put back in the landfill and capped. A fourth could be metals and perhaps also batteries and e-waste which can go to recyclers.

Waste management requires political will, municipal vision, technological awareness and business sense. It is complex and what the garbage mountain at Ghazipur needs is a special purpose vehicle (SPV) that can rapidly come up with a range of viable solutions.

A model worth examining is the one that was followed by Jabalpur in Madhya Pradesh some years ago for which Zonta group's consulting arm InfraEn India Pvt Ltd provided project management consultancy.

An active and aggressive municipal administration in Jabalpur first set up a waste-to-energy plant and then started mining the garbage.

It is a good way to go except that when the legacy waste was taken care of in Jabalpur, there wasn’t enough waste coming in from the city to keep the plant running.

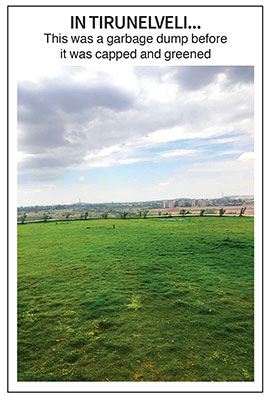

When legacy waste had to be dealt with in Tirunelveli, it was merely capped and the surface greened, recalls Kumar. But in 2016, the government’s rules on waste management changed and biomining was introduced.

Reuse of waste after mining it from a dump makes waste management a balancing act more complex than ever before. Technology and business realities have to be taken into account. The participation of citizens is also important. Everything has to hang together in a calibrated effort if cities are to be cleaned up quickly.

Comments

-

MadhuDevineni - March 21, 2022, 3:21 p.m.

This needs to be fixed on top priority. If it can’t be solved in the capital of India, how are we going to solve this increasing garbage problem? The garbage is to be fixed at source of generation with separation in 4 to 6 varieties like composting materials to be composted in the specified places and in premises if they have space. Next the recycled materials like plastics, cartons to be separated for recycling to be collected and handover or sell to recyclarers. Then some dangerous materials like medical wastes, tablets, aluminum wrappers, injection needles, electronic products, and any other dangerous materials. The packages should contain these details by separate baggage. Most of all the people should be asked to carry cloth or strong multi usable plastics to carry their purchases like vegetables and groceries. Finally, only the materials which can’t fall into any of these categories should be packed and to be collected by the municipality. The 1 per cent tax included in GST is not being used properly.