Compactors take over, ragpickers fade away

Subir Roy, Kolkata

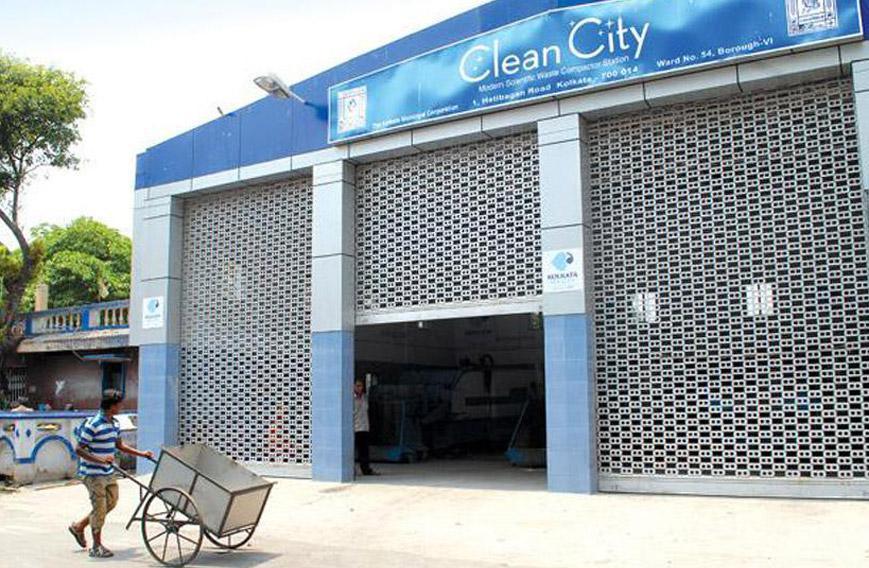

There is a crisis brewing among scavengers or ragpickers, as they are more respectably referred to, in Kolkata. Over the last few years the city has witnessed the arrival of “compactors”, funded by the Asian Development Bank and “compactor stations”.

The smartly built stations which house the compactors, have been replacing vats — filthy overflowing collections points for garbage, an eyesore and a health hazard — that have been the hallmark of the city for as long as people can remember.

The ability of the Kolkata Municipal Corporation (KMC) to replace the vats with structures and equipment which are new, neat and supposedly scientific has been widely appreciated and unsurprisingly the Trinamool Congress has recently re-won control over the state’s premier civic body for another five years.

But in the process, the compactors and stations have come to pose an existential threat to the city’s over 100,000 ragpickers who live by collecting recyclables like paper, plastic, glass and metal from the garbage and selling them to aggregators.

Thanks to the compactors, their daily income is down by around half, from `200-250 to `100-150, according to Shafkat Alam, joint secretary of the Tiljala Society for Human and Educational Development (Tiljala SHED, named after a deprived east Kolkata area), the NGO which has promoted the Association of Ragpickers of Kolkata. The latter has been in existence for 15 years and has over 300 members. Founded by a retired government school teacher, Muhammad Alamgir, Tiljala SHED has for over two decades worked among ragpickers in mostly deprived slum ridden east Kolkata which has a large concentration of Muslims.

If the current state of affairs continues, according to Alam, the city’s ragpickers will soon run out of any little savings they may have had and thereafter be driven to pure destitution and forced to take to begging and crime.

While some ragpickers have lived in the city’s worst slums (yes, there are better and more awful slums) for several generations, many landless labourers, mostly from the scheduled castes and Muslims, have migrated from the countryside in search of some kind of income and begun right at the bottom of the economic and social ladder, scavenging in the city’s garbage for recyclables, as they have absolutely no education or skills.

The clouds looming over the future of ragpickers is the result of the role compactors play in the disposal of the city’s garbage. Earlier, the municipal sweepers would bring the garbage collected from households and sweeping of the streets to the vats where it would stay for a time, as lorries to take the garbage to the city’s landfill, Dhapa, would invariably take time to come.

This would provide the ragpickers a critical window of opportunity, allowing them time to forage among the garbage and collect the recyclables in separate sacks for plastics, paper and the like. This resulted in vats with a permanent stock of garbage and beside them a small collection of ragpickers with their filthy looking sacks of sorted recyclables. Some even lived on the pavement next to the vats and exercised territorial rights over a vat and its garbage.

The change today is that the garbage from the handcarts goes straight into the compactors which compress it, taking out water and reducing both volume and weight. Trucks, specially designed to carry containers in which compacted garbage is collected, come with some regularity to take the containers away to the landfill. Usually by midday, the compactor station is free of garbage, cleaned, washed and dusted with disinfectants. Initially, ragpickers were gone from around them but at some compactor stations there is a sign of returned ragpickers, sorting the recyclables in separate sacks.

While doing away with vats is an absolute positive, the problem with compactors is that they disallow the segregation of recyclables as you cannot look for plastic or paper in compacted garbage. Segregation and recycling are the sine qua non of sustainable living and all developed countries and increasingly others are going in for it. These have the added advantage of reducing the amount of solid waste that has to be dumped at a landfill and thereby extend the life of a landfill. This is extremely useful at a time when virtually every Indian city is running out of landfill space.

The way to ensure that segregation and recycling take place and vats do not make a reentry is to organise segregation at source by households, municipal markets and restaurants and other commercial establishments. But KMC does not have any plans of introducing segregation by households in all the municipal wards of the city.

Such segregation was introduced in seven of the 144 wards in the city some time ago and according to Debobrato Majumder, member-in-charge of conservancy in the mayor’s council, only a very small amount of recyclables is being handed over by households in the seven wards which have been provided with separate bins for compostables and non-compostables.

His explanation is that the proportion of organic waste is very high in the solid waste generated by Indian households and whatever can be recycled like old newspapers and empty bottles has for long been segregated by households and sold to the bikriwala or kabadiwala.

Indians have also not bought into the disposable culture prevalent in the richer countries. Majumder narrates the story of how a 1970s vintage TV set, no longer functioning, has not been thrown away and still rests in one corner of his house as it used to be viewed by his father and so has become a family heirloom.

On the other hand, ragpickers have survived before compactors came by extracting recyclables from the garbage that city households, markets and restaurants have thrown out. A ragpicker’s working day begins well before dawn when he starts prowling the city’s streets to pick up any kind of recyclable before municipal sweepers can carry them away and ends around midday at a vat where he lends his hand in the sorting and thereby lays claim to some of the recyclables and their sale value. Walking close to 10 km in a day is routine for a ragpicker.

This sorry lot is worried at the prospect of more and more compactors arriving and the number of vats dwindling. Majumder says there are now 42 compactors in the city and the number is likely to go up to 100 within the current financial year. In his scheme of things compactors have come to stay and most citizens are for them. On compactors gobbling up recyclables, his answer is, “There are positives and negatives in every situation. Besides, nobody wants vats with their mounds of garbage and foraging man and beast (stray dogs).”

Ragpickers have a lower life expectancy than the overall population, few going beyond 60 and the plight of the aged among them is particularly severe. Youngsters want the elderly to go wherever they can as a single jhopri cannot accommodate more than one family. The association people speak of one couple, Palan and Molina Haldar who must be in their sixties. Palan is blind and so they work together, with the man resting his hand on the shoulder of the woman who forages for recyclables. But Molina is too weak to carry a load so what she collects is put in the sack which Palan carries.

Children, as soon as they are old enough, join their parents in the daily odyssey of collection. Some whose parents are better off and want their children to get some education, go to municipal schools in the morning. Tiljala SHED runs afternoon schools for them so that they get a bit of extra help, what private tutors would provide for the better off.

A major challenge for ragpickers is to get any kind of official identity which can then pave the way for them to be part of government welfare programmes. Alam says 250 members of the association applied for voter ID cards and 150 got them. One big issue is being able to give an address as they mostly live in unrecognised slums. So you get things like everyone in one cluster giving one address in an adjoining recognised slum as their address. But perhaps the biggest hurdle is being able to get a Form 6 with which you apply for a voter’s ID. Officialdom very quickly rejects applications with incomplete paperwork.

In getting some kind of official identification the association finds helpful the West Bengal government’s State Assisted Scheme of Provident Fund for Unorganised Workers. But there is a problem for ragpickers as there is no official category for them and they describe themselves as daily wage earners or housemaids. This is in contrast to the situation in Delhi where an NGO, Chintan Environmental Research and Action Group, has issued identity cards to members of the “Safai Sena” which bear the logo of Delhi’s municipal corporations.

Ragpickers have a notoriously short perspective on life. What they earn in a day they mostly spend by the end of it by having a decent meal and drinking. They are loners by nature, prowling city streets from the early hours of the morning. They do not want to be tied down to a daily routine. Alam says it is a headache getting together a group at one time to go to some government office for paper work. A common refrain among middle class people and city civic staff is that ragpickers refuse decent employment and prefer their life of addiction and petty crime.

Ragpickers exist only in poor societies where alone you can find human beings willing to do such demeaning work. Once they are a little better off they will quit this work and move on. So if compactors make them redundant then officialdom and civil society have to join hands in bringing them into the social mainstream. One way is for them to be able to find decent work and a good starting point could be the “100 days” urban jobs scheme fashioned by the state government after the centre’s rural employment programme. Under this one can see men and women diligently sweeping city streets in selected areas.

Majumder says he will be happy to “offer jobs under this scheme if ragpickers come as a group and promise not to hang around compactor stations sorting recyclables.” When I played this back to the association people they told me, “This is news to us; we will take it up with the officials concerned.” In any case it is income for 100 days in a year of 365 days. What does the ragpicker do for the rest of the 265 days?