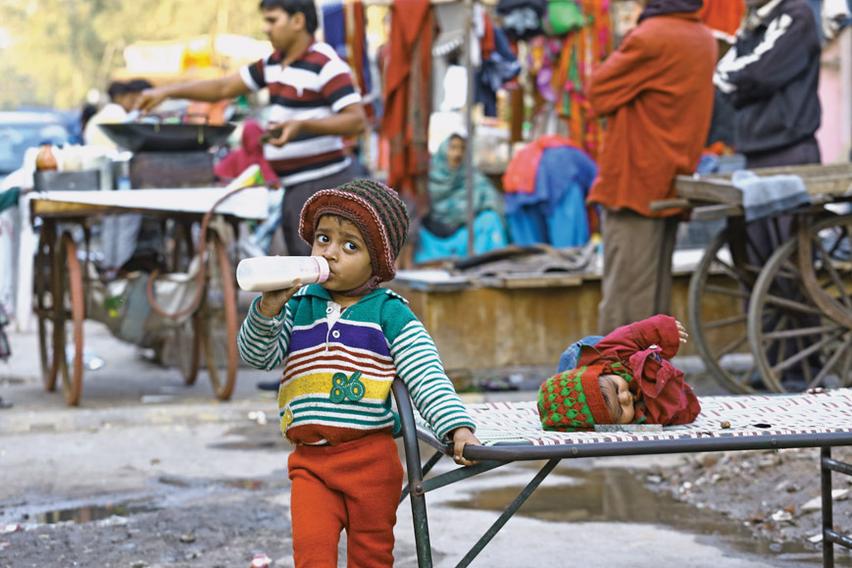

Child health sinks in slums

Civil Society News, New Delhi

A household survey carried out by CRY (Child Relief and You) in 15 slums of Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai, Bengaluru and Kolkata reveals alarming data on child health. Almost half the children surveyed, between one and six years of age, were found to be malnourished.

Surprisingly, Chennai had the most number of malnourished children with 62.2 per cent being underweight. In Kolkata, the figure was 49 per cent and in Mumbai 41 per cent. In Delhi, 50 per cent of children living in slums were found to be underweight. Bengaluru fared better at 33 per cent.

There has been some marginal improvement in stunting. In Delhi, 45 per cent of children suffer from stunting, a small improvement from National Family Health Survey (NFHS) data which showed 51 per cent in 2004-05. In Bengaluru, stunting has gone down to 17 per cent from 19.8 per cent.

Most of the households surveyed consisted of migrants who worked as daily wage labour and in the unorganised sectors of the city. The women go to work and have little time to care for their children.

Anganwadis that come under the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) have emerged as the most critical space from where the health of children could be improved. But in Delhi and Bengaluru only 47 per cent of children are enrolled in anganwadis. In Kolkata, the figure is 60 per cent. Around 25 per cent of children are sent to private preschools.

According to CRY’s survey, more than a third of the children in the five cities surveyed had not been de-wormed. In Delhi, half the children did not receive the Vitamin A and IFA (iron and folic acid) supplement and about a third had not been de-wormed.

The advantage for children who go to the anganwadi is that, unlike in preschools, they receive health services like de-worming, Vitamin A, and iron and folic acid tablets. For instance, 73 per cent children enrolled in anganwadis received the Vitamin A dose in the five cities compared to only 52 per cent in private preschools.

The anganwadi worker, by and large, monitors the growth of the child but she doesn’t inform the parents about their child’s health. So, though growth monitoring was done for 70 per cent of children, only 48 per cent of parents were informed. In Delhi, for instance, 60 per cent of parents did not even know that their child was malnourished. In Bengaluru 74 per cent of parents said the anganwadi worker did not give them any feedback about their child.

Both parents and children were happy to go to the anganwadi. Though there is a lot of room for improvement, perceptions about the anganwadi were positive; 96 per cent of parents feel safe sending their children there and 82 per cent say it is a child-friendly space.

Only Chennai and Bengaluru were rated well for preschool education. The anganwadis in both cities were well-stocked with learning material and toys.

Some anganwadis provided hot, cooked food. In Delhi parents received dry rations.

Coverage of immunisation is not 100 per cent. Less than one-third of the children (about 31 per cent) in Delhi under the age of three received one dose of recommended vaccination. A gender imbalance is seen here with only 25 per cent of the girls receiving at least one dose, as compared to 39 per cent of the boys. In Bengaluru, 78 per cent of boys and 77 per cent of girls had been immunised. In Kolkata, 58 per cent of children under three had received one form of vaccination.

Soha Moitra, Regional Director (North) for CRY, said they had been trying to speak to officials about the findings of their report so that they could map a joint action plan with the government to combat child malnutrition in urban slums.

Moitra said the survey revealed that an awareness campaign to combat malnutrition with messages for parents and service providers was essential. Parents did not know their child was malnourished or what to do about it. They were unaware of the kind of services that should be provided by the ICDS and the anganwadi. Neither did they know the number and types of vaccinations needed for their child.

There is also need to rationalise the many schemes drawn up for child health and to ensure convergence between various government departments responsible for implementing them.

Also, training programmes for anganwadi workers could use inputs from CRY. The anganwadi worker measured the child’s weight but not height, an essential marker of malnutrition. The worker was under-paid and under-skilled and she could be saddled with too many duties. “The anganwadi worker is expected to go from house to house. The population she is expected to cover is huge and her bandwidth limited. The health-seeking behaviour of the community needs to be strengthened,” said Moitra.

In urban slums there is also no safety net for children. Most parents are migrants and don’t always have documentation so their access to cheaper food through the public distribution system is limited. Only about 50 per cent of children are sent to anganwadis. “This probably means that there aren’t enough anganwadis or parents are rejecting them because the quality of service is not good. The child suffers because anganwadis do provide supplementary nutrition, immunisation, iron and folic acid tablets and so on. The most critical years, 0-3, are lost,” says Moitra. There is no regulation of crèches which infants are sent to either.

The ICDS, along with the food security law, is a comprehensive scheme, says Moitra. “But it isn’t a law. The ICDS should be an entitlement guaranteed by law.”