The market beyond drip

Civil Society News, Hyderabad

When plants and trees need water how much are they really asking for and when and how should it be delivered? Figuring that out can mean a good chance at cracking a diverse customer base in rain-fed, water-starved parts of India where orchards, flower beds and vegetable gardens all cry out for more efficient irrigation.

K.S. Gopal of the Centre for Environment Concerns (CEC) has designed a system that is more efficient than drip irrigation because it is subterranean and delivers moisture to the roots of plants.

He says he has done it by talking to farmers, using practical science, and, most important of all, by observing what plants communicate about their water needs at different times in their lifecycles.

Gopal calls his technology SWAR or System of Water for Agricultural Rejuvenation. He already has paying customers for SWAR and Rs 31 lakh of business has been booked by CEC since January. It expects to do Rs 1 crore as turnover in the course of the year.

Gopal has received two significant global awards, which recognise SWAR as an innovation. The commercial possibilities are many. Clients have so far mainly been farms but the government has shown keen interest and entry into the national greening programme could mean exponential growth for the business — for instance the National Highway Authority of India wanting to grow trees along the roads it builds. One of the awards gave Gopal working capital of half a million dollars. It has subsidised the operation and so it is difficult to figure out profits clearly. But as the business grows it will be transferred from CEC to SWAR Technologies. and then numbers will be clearer.

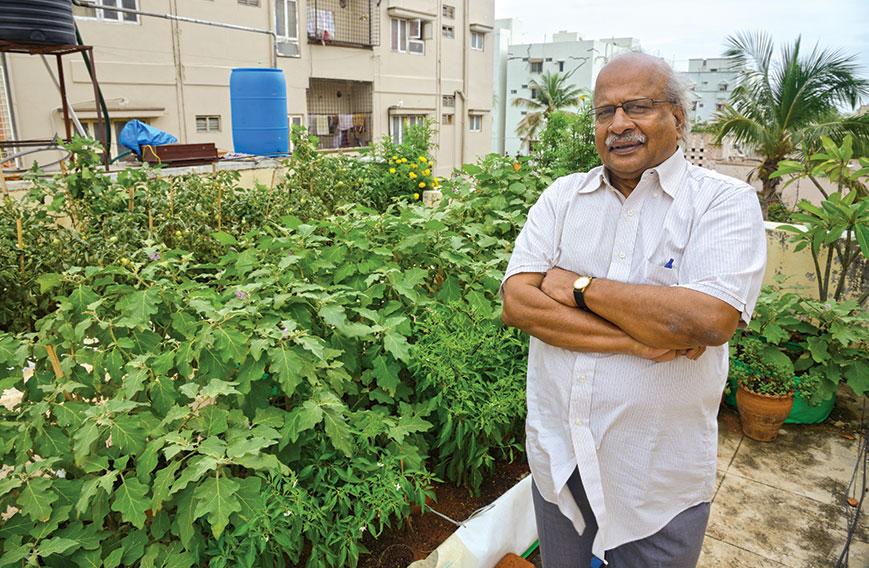

Gopal, 64, is a serial social activist. He is one of the founders of the Deccan Development Society and when he moved on from that there were sundry pursuits until he joined CEC in Hyderabad in 1993. He has a management degree and believes it has given him an orientation that is useful for solving development-related problems.

He was assessing the working of the rural employment guarantee scheme when he saw that the single biggest asset creation was in water. But rainwater harvesting essentially put water back into the ground. There was a need to use it efficiently for agriculture so that it could contribute to rural prosperity.

Fruiting tress

Gopal began designing a sub-surface system that could take moisture directly to the roots of plants without overwhelming them and also preserve the microorganisms in the soil on which plants draw.

The system needed to be in dialogue with plants. It had to provide an osmotic arrangement of demand and supply from which natural efficiencies would result. It meant rethinking what plants and trees require at different stages of their growth.

“The economic threshold yield of a fruit tree comes from year seven onwards. You can see the yield of the chikoo and mango (earlier) but that’s not the real yield or the economic yield. For teak the economic yield comes from the 11th year,” explains Gopal.

So, as a tree starts growing its demand for moisture keeps increasing. Higher yield is reflected in greater demand. A farmer who digs a borewell to get X amount of water for Y number of plants finds the maths has changed. After a point the farmer is unable to irrigate all the plants and decides to take care of a few and let the rest die from moisture stress.

“Manmohan Singh appointed an ICAR (Indian Council of Agricultural Research) committee to look into the high mortality of the adult fruit bearing trees in Maharashtra,” recalls Gopal. “They came up with a report. But the core problem was how do we tackle moisture stress.”

“When the tree is fully adult and at its peak performance, it is dying because there is no water. With different species, we ration water by supplying it to the root system. Drip irrigation is on the surface and has no concept of rationing. Our technology serves a dual purpose," says Gopal. “One purpose is to increase productivity when the going is good. And the second one is to keep the tree alive when the going is bad.”

“My efficiency is I use one-fourth of the water that drip does. I am happy to say this is the first technology where I can keep the trees alive. I have been doing this since two years and this year we did it on 2,000 trees of different species.”

Gopal says he teamed up with farmers and used the knowledge of scientists. The farmers had both the problem and the solution, but they did not know how to implement it.

“The farmers wanted to know how they could look after all their trees equally instead of just saving a few and leaving the others to die. They should at least survive during the summer period so that they have the chance to recoup again. These farmers gave an analogy — if we have less food and four kids to feed what we do is feed each one a little less food. Everyone’s stomach will not be full but at the same time no one dies.”

The challenge was to design a system for distributing water in much the same way: each member of a family eats less so that all can survive.

Gopal has used his system in and around Anantapur, Hyderabad, Usmanabad and Bijapur.

Vegetable garden

In Hyderabad, the system has been tried in the vegetable garden at Prakash’s bungalow. He is Gopal’s old buddy of many years. It is on the verandah of Prakash’s beautiful, rambling home that Gopal first holds forth on himself and how SWAR works. He is a short, intense and amiable man who talks continuously about himself and SWAR. Ideas, thoughts, experiences, dates tumble out.

In Prakash’s garden a little later we get to see how SWAR works. Water stored in an elevated tank flows through a network of pipes to the roots of the vegetable plants.

The water first collects in earthen pots, which are underground at root level. From the pots small, narrow pipes dispense the water in tiny drops into the surrounding soil, making it moist and conducive for microorganisms.

Through the moisture a harmonious relationship grows between the earthen pot and the plant whose roots reach out in search of moisture and nutrients to the extent it needs them.

What is needed is “wetting and sweating”, says Gopal, and the earthen pot is crucial to this process. Thin pipes sticking out of it from a little above the lowest level provide the wetting when water flows into the pot once a day.

But once the moisture in the soil dries, the fibrous roots of the plant reach out to the pot where some water remains. This is when the sweating happens as the roots draw the remaining water in the pot.

There is one pot for three or four vegetable plants. But for trees there is one pot per tree.

Pots that sweat

It is important that pots are baked at between 450 and 550 degrees centigrade. It is enough to tell a potter to make pots that sweat. Quality of soil does make a difference, but only marginally so.

Traditionally, farmers bury earthen pots containing water to create moisture in the soil. A cotton wick is put in a hole at the bottom of the pot. But the wick becomes hard in no time and no water goes out. The result is there is only sweating.

But in the SWAR model the thin plastic pipes deliver water from the pot and create ambient moisture every time the pot is filled. The remaining water then comes out through sweating caused by suction when fibrous roots engulf the pot.

There are innumerable innovations to keep the system working. For instance, tiny bags of sand are used outside the pot to keep the moss from choking the plastic pipes. The purpose of the system is to reduce the consumption of water to the minimum and create ambient moisture, which puts the plant at ease.

“Water should be eased out slowly. It’s not just water plus plant, but it is water plus microbes in the soil. This kind of irrigation system — moisture and microbes, wetting and sweating — is ideal in tropical countries,” says Gopal.

The savings are pretty impressive. A tomato plant survives 120 days and requires just 150 litres during this period under SWAR. But under drip irrigation, 600 litres are consumed.

Mango at an early stage requires eight litres a day under drip irrigation but under SWAR just five litres a day is needed. As it matures, mango is given 150 litres a day, but under SWAR it is just 30 litres.

Knowing when to irrigate a plant is important. When it is fruiting the demand is more. But there are times, as in the case of the mango, when no water may be needed.

Plants are also wired to draw water during the monsoon. So, if the rains are deficient, it is a good idea to give them water so that they can make up the shortfall. Gopal first noticed this with sitaphal or custard apple.

“If the monsoon doesn’t give rain, give it some water. And it will transform in yield both in terms of size and more yield,” Gopal explains.

It is still early days for SWAR but there are opportunities that present themselves in urban vegetable farming, saving old trees and the growing of orchards.

“Hopefully we will get some people next year who can run it as a business and certain revenues will keep coming to us so that we will continue to have our fun. Because development is more or less fun,” says Gopal.

Comments

-

TEJASWINI M - April 1, 2020, 4:04 p.m.

Hi Sir, I felt extremely happy after reading article about SWAR and your work. In my land i was planning to implement similar technique i , e subsurface irrigation . Your work in this field would be extremely helpful for me and people of my village.we are based out of chitradurga, karnataka. Please provide me your contact information. looking forward to talk to you.

-

Veerabhadra sastry - March 29, 2017, 8:57 p.m.

What is the distance of pot from plant.Do we need change distance while plant is growing? What about the intercultivation? Will it possible when the pot is inside? Please reply

-

Dr. Suresh Kulkarni - Dec. 7, 2016, 9:05 a.m.

Dear sir, This is innovative method of irrigation for increasing production and saving water with increasing water efficiency. It is gift for farmers.

-

PRAMOD DESHMUKH - Dec. 6, 2016, 4:50 p.m.

Valuable info and innovation . We will try this technology in our Krishi Vigyan Kendra [ KVK ] and keep u updated .

-

Raghu Rajan - Nov. 25, 2016, 1:18 p.m.

Great Work, Gopal, you are truly a Gopal who will rejuvenate our farms to world class standards,

-

LL - Nov. 24, 2016, 10:36 p.m.

WOW. Phenomenal. Inspiring. I so hope this becomes available in all places..... great work and thanks for the article - quite informative.

-

Kaylyn - Nov. 5, 2016, 5:14 p.m.

Woot, I will cetarinly put this to good use!

-

Vimal Mohan - Nov. 2, 2016, 12:29 p.m.

Very informative article.