Sahil Dharia:'Leave manufacturing to us because that is our core competence'

Sanitary napkins need a pro to get them right

Kavita Charanji, New Delhi

When the Nalanda Foundation set up a small sanitary napkin making unit in Ghazipur in east Delhi in 2014, the goal was to give women waste-pickers an alternative livelihood and also spread awareness about menstrual hygiene. Local women would make a living from producing low-cost napkins which they would sell as well as promote.

But for all the enthusiasm that went into setting up the unit, it didn’t do well right from the beginning. The napkins were expensive and uncomfortable to use. Two years later, Anurag Kashyap, associate director of the foundation, found himself shutting down the Ghazipur unit.

But for all the enthusiasm that went into setting up the unit, it didn’t do well right from the beginning. The napkins were expensive and uncomfortable to use. Two years later, Anurag Kashyap, associate director of the foundation, found himself shutting down the Ghazipur unit.

From being small manufacturers of a rudimentary napkin, it was decided to team up with Soothe Healthcare so that the women could instead sell and promote better quality napkins.

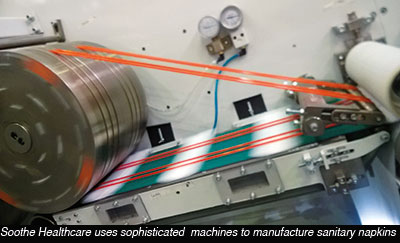

Soothe Healthcare’s factory, which manufactures the Paree brand, has modern machines that produce 510 million high quality sanitary napkins a year. The company has just one to two percent market share but intends to capture 10 percent.

Only 20 percent of Indian women use sanitary napkins but numbers are rising and in recent years several small manufacturers including NGOs, have plunged into making sanitary napkins. But manufacturing hygienic, comfortable, absorbent and inexpensive sanitary napkins is a sophisticated operation and often cannot be achieved by a cottage industry, as Kashyap realised.

The Nalanda Foundation is the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) wing of Infrastructure Leasing and Financial Services Limited (IL&FS). The Ghazipur unit was being run by the Gulmeher Green Producer Company, (GPCC), a social initiative set up by IL&FS in 2013.

Since IL&FS was setting up a waste-to-energy plant at the Ghazipur landfill it wanted to create alternative livelihoods for waste-pickers who would be left jobless. Its small sanitary napkin unit could hardly be compared with Soothe Healthcare's fully mechanised one. Yet it was important that the final product be affordable and comfortable to use.

“Our motive is to provide a livelihood to waste-pickers. On the other hand, Soothe Healthcare is a profit-making venture," says Kashyap.

The waste-pickers had been trained by the Institute for Development Support, an NGO based in Uttarakhand, to make products like attractive greeting cards, file folders, note pads, gift boxes and coasters from recycled paper and waste flowers collected from the Ghazipur wholesale flower market. A stitching unit, mini-bank and an educational wing had also been set up.

Adding a sanitary napkins unit looked like a promising endeavour in 2014. “We thought that production of sanitary napkins would be an additional income stream for the women and help get them off the landfill. We also thought it would improve the health parameters of the community,” says Kashyap. Besides, the unit required minimal capital investment, space was available, and low-cost sanitary napkins seemed to have a ready market.

Gulmeher tied up with Aakar Innovations, manufacturer of Anandi, a low-cost sanitary napkin brand. Aakar’s job was to provide technical training to the women, while IL&FS made a capital investment of Rs 5 lakh to Rs 7 lakh in the project. Marketing was to be taken care of by Aakar.

The sanitary napkin unit provided employment to 15 to 20 women working in two shifts, producing regular as well as biodegradable napkins. They were paid Rs 5,000 per month for a daily six-hour shift. The women were also trained to raise awareness about the importance of menstrual hygiene in their community. They could earn more by marketing the napkins independently. It sounded good on paper. But soon after the unit went into operation, it became clear that all was not well.

“Although the machinery was low-cost, the actual product was not low-cost if you built in the wages of the women, rent, transportation and other such overheads. The price of the napkins worked out to Rs 3 to Rs 4 a piece so we couldn’t market them as low-cost products,” says Kashyap.

Sangeeta, supervisor at the Gulmeher Livelihood Centre, agrees. “At the lower end our napkins sold at Rs 22 for a packet of six. In the upper category, a packet of six was priced at Rs 40.”

Poor quality and inadequate marketing added to their problems. “The centre is in the middle of a dumpsite. Although we were giving women gloves, masks and trying to keep the product as hygienic as possible with an infrared steriliser, quality was not up to the mark. Sometimes the glue would get unstuck and cotton would come out of the napkin. The women who produced the napkins weren’t using the napkins themselves,” says Kashyap.

The unit didn’t have economies of scale either. On an average, the women produced 630 napkins a day, says Kamla Joshi who is in charge of the centre.

Marketing the product proved to be difficult. “Aakar was supposed to buy the napkins from us, but that didn’t happen. They would say they didn’t have place to stock our products or cite other reasons and eventually they stopped buying altogether. Our workers were left idle,” she says.

So instead of boosting incomes, the unit became a drain on Gulmeher’s resources. Finally, in 2016, the sanitary napkins unit was shut down. Some of the women workers were absorbed into the stitching and paper bag units while others found employment elsewhere.

At a chance meeting, Kashyap got to know Sahil Dharia, founder and CEO of Soothe Healthcare. He told Dharia about the ailing sanitary napkins unit and asked for possible help. Dharia visited the unit and was appalled at the sight of 20 women manually making the napkins, gluing and drying them under a fan so that they wouldn’t attract fungus. “I thought to myself, can this product really be sold for the use of women? They are better off using cloth. An unhygienic and poor quality product was a big no for a big company like IL&FS,” says Dharia.

At a chance meeting, Kashyap got to know Sahil Dharia, founder and CEO of Soothe Healthcare. He told Dharia about the ailing sanitary napkins unit and asked for possible help. Dharia visited the unit and was appalled at the sight of 20 women manually making the napkins, gluing and drying them under a fan so that they wouldn’t attract fungus. “I thought to myself, can this product really be sold for the use of women? They are better off using cloth. An unhygienic and poor quality product was a big no for a big company like IL&FS,” says Dharia.

He told Kashyap about his own factory in Greater Noida that had got US Federal Drug Authority (FDA) registration for its good manufacturing practices. “They believed that they were creating a good product. When I showed Kashyap how we worked, he understood where they were going wrong,” says Dharia.

Around Rs 35 crore has been invested in setting up Soothe Healthcare’s factory. Currently, Paree has not made profits, but Dharia believes that his company will begin making money a few years down the line.

Dharia is clear that his company is not a social welfare enterprise. “Our motivation is to enter a blue ocean or virgin market, make profits and follow the idea that what is good for the company is good for the community,” he says.

Before starting Soothe Healthcare, Dharia worked for nine years with Thomson Reuters. He was their Global Head of Operations, Investment Research Content, supporting operations with a $200 million revenue footprint. He is a charter member of TiE, a FICCI Young Leader, and on the executive council of CII Young Indians.

Dharia believes that high-quality, competitively priced products, along with a good reputation, will take his company far. Already, Paree sanitary pads are available across India in retail stores like Reliance, Walmart, Metro, More and WH Smith. The Indian sanitary napkins market is dominated by Proctor & Gamble and Johnson & Johnson.

Dharia is confident that in the next two years, the company will be able to capture 10 percent of the market. He believes that is doable because MNCs are slower in decision-making and their priorities are Western markets. Eventually, local brands have more resilience and a better understanding of their home turf. “Why would MNCs spend time understanding what the Indian consumer needs? But that is my business,“ says Dharia, who is competing with big brands like Whisper, Stayfree, Kotex and Sofy.

There is a cost advantage in buying Paree. A packet of eight has a maximum retail price of Rs 30 to Rs 32, which is Rs 2 cheaper in the base category than its nearest competitor. Its premium category, called Pariz, costs more. “The product is more expensive because it is far superior. We have better absorbency, better top sheet, better comfort and are one of the first sanitary napkin manufacturers to bring in a soft feel,” says Dharia.

Soothe Healthcare’s former brand ambassador, badminton player Saina Nehwal, invested Rs 1 crore in the company. The company also gets involved in awareness campaigns for social good. Recently, Soothe Healthcare, along with the Times Group, launched a menstrual hygiene campaign in Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and Punjab with Miss World Manushi Chhillar.

Soothe Healthcare has trained staff called Paree Didis to go with a doctor-approved script on menstrual hygiene to schools and colleges in the northern states of India.

“Our Paree Didis also train women at ITC e-choupals and rural agri-trading hubs, to educate women on menstrual hygiene and sell packs of Paree. We thereby create women entrepreneurs who make Rs 4 per pack of eight napkins through each sale,” says Dharia.

Paree has found common ground with Gulmeher. Fifteen to 20 women from Gulmeher have been trained as Paree Didis.

Dharia thinks it is a great way of boosting enterprise among the women. “We are saying, leave the manufacturing process to us because that is our core competence and ask the women to sell the packs. We are training 50 women who will become Paree Didis themselves. We have now received a second order of sanitary napkins from them,” says Dharia.

Comments

-

Sachin Sachdeva - May 8, 2018, 5:32 p.m.

So what happened to the 15 women who were making napkins? What was intended to be a social enterprise ended up being taken over by a bigger company ! And primarily because IL&FS chose a poor solution for poor women.