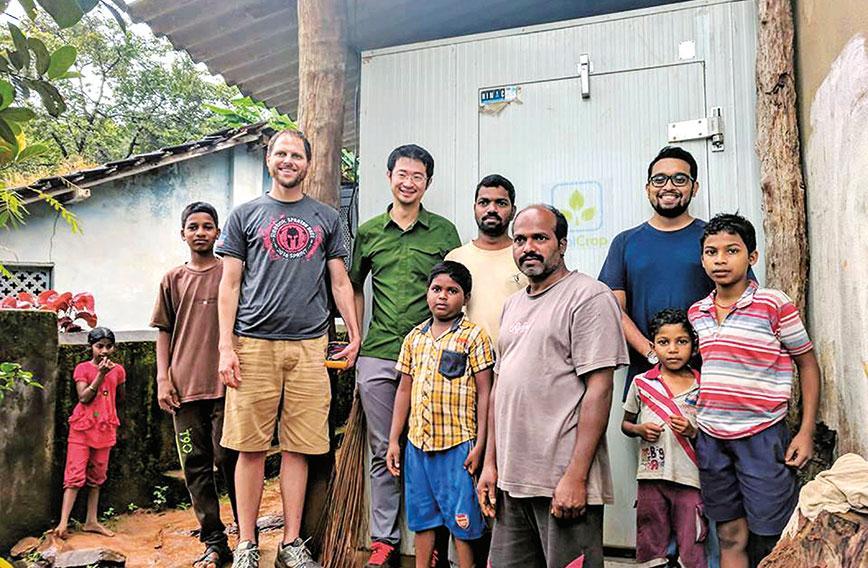

Kendal Nowooin, George Chen and Niraj Marathe (in blue T-shirt) outside the cold storage they built for Joida village

Cold storages for villages: A mini answer from CoolCrop

Shree Padre, Mangaluru

This April, for the first time, the Kunbi tribal community in Joida will harvest their crop of pickling mangoes without a trace of nervousness. They now have a cold storage right in their village where they can keep their mangoes before taking the fruit on a long journey to the nearest market. The mangoes, a local wild variety called appe midi, have to be harvested at a tender stage else they lose their value.

Joida, a predominantly Kunbi tribal taluk, is very remote and doesn’t have basic facilities. From some areas, villagers trudge 20 to 30 km to catch a bus; the nearest primary health centre is 20 km away. Last May, 27 villages got electricity for the first time — for just one day.

But this same taluk, with so little to speak of, now has a smart cold storage. It was gifted to the villagers by CoolCrop Technologies, a company which has set out to provide storage solutions for small growers in remote areas. The company had wanted its Joida cold storage to be a hybrid one connected to the grid with solar power back-up. But the Karnataka State Electricity Board didn’t allow it.

Built at a cost of Rs 4 lakh, it is a low-cost machine which is sheltered under asbestos sheets and attached to the house of a young farmer, Ghanshyam Derekar, as per a decision taken by the taluk’s Shri Siddhanath Cold Storage Committee.

“We couldn’t take full advantage of the cold storage last year,” says Jayananda Derekar, a local social activist. “There are a couple of pickle companies which are very interested in buying our appe midi. Three farmers, Shashank Derekar, Sachin Derekar and Ghanshyam Derekar, are keen to make full use of the cold storage this year. We grow vegetables like tomato, too. Except in July and August, we will be using the cold storage round the year.”

Joida is, of course, famous for its tubers. Last season, the Kunbis stored their prized big tuber called mudli (Colocasia esculenta) for a few months. During the tuber harvesting season in November and December, the mudli, which is much prized by the Saraswath Brahmin community, sells for Rs 70 per piece. By February, the price of the same tuber rises to Rs 120. Keeping mudli in the cold storage enabled Ghanshyam Derekar to earn Rs 6,000 extra in December 2017.

“We are focused on building small cold storages that run on grid or solar power for marginal farmers,” says 31-year-old Niraj Marathe, founder of CoolCrop. The company’s objective is to help low-income farmers earn more money for their crops instead of selling them at a throwaway price just because they don’t have storage facilities.

India is the world’s second largest producer of fruits and vegetables. But it also tops in food loss and waste. Harvest and post-harvest losses in fruits, vegetables and grains come to a whopping Rs 44,000 crore every year. There are large cold storages in big cities and smaller ones mainly for the dairy industry, but rural areas need mini cold storages where fruits and vegetables can be locally stored. It is here that CoolCrop is a pioneer.

Initial foray: Marathe is a postgraduate in solar technology. He did a course on energy entrepreneurship in Germany and won the Siemens Students Award for his concept on solar powered cold storages. An internship from GIZ in Germany enabled him to travel deep into the rural heartland of West Bengal, Bihar and many other states for six months. Wherever he went, he saw wastage of horticulture crops and sales at throwaway prices.

He felt the need to help underprivileged farmers. As it happened, in 2016, Marathe met Balachandra Hegde Sayimane, a farmer-journalist in Bengaluru. Sayimane was eager to help in Joida’s development. So when Marathe told him he was keen to construct a cold storage facility for a needy rural area, Sayimane at once suggested Joida. After several visits to Joida and many rounds of discussion, Marathe’s dream turned into reality on one side of Ghanshyam’s tiny house in Joida’s Deriya village.

“The company is committed to helping underprivileged farmers,” says Sayimane. “Kunbis are used to storing their tubers in an underground pit. Convincing them to use the cold storage

has been a Herculean task. This is probably the first time in the world that tubers are being stored in a cold storage. CoolCrop couldn’t get information on data like best temperature range, not even from Africa.”

Since tubers have a longer shelf life than perishable fruits and vegetables the economic viability of the cold storage can be ensured if Joida’s other crops, like tomato and mangoes, are stored in it, says Dr Subramanian Ramanathan, retired principal scientist of the Central Tuber Crops Research Institute (CTCRI). Mudli qualifies and so do appe midi and tomato.

The size of the cold storage is determined after studying the cultivation and harvesting pattern of the region. The Deriya model’s size is 10x8x6 feet which creates a capacity of 500 cubic feet or three to four metric tonnes. Joida can now store 500 to 600 mudlis and earn an additional income of Rs 25,000 by waiting for the price to escalate during the off-season.

Temperature and humidity in the cold storage can be adapted to different crops. Tomatoes can be kept for three weeks under 7 — 10 degrees Celsius. Cabbages will last for three to six weeks in 2 to 4 degrees Celsius. Tubers can last for three to four months. Electricity consumption for the Joida cold storage, which is a three to four metric tonne model, is just 10 to 12 units for 24 hours, when it is filled with produce.

Ghanshyam Derekar with his tubers in the cold storage

Ghanshyam Derekar with his tubers in the cold storage

Pilot projects: CoolCrop has a five-member team. While Marathe is CEO, Kendall Nowocin, who is American, is a co-founder and Chief Technological Officer. He visits India once in two months. George Chen, another co-founder from the US, collects data on the prices of crops for the past 10 years and helps to build the xscompany’s market information system. Srinivas Marella is sales consultant. Alok Das works in Odisha and looks after systems and marketing data collection. Wei Ma, also from the US, is an internee who assists Chen.

After the Joida project, the CoolCrop team didn’t sit idle. They identified two more deprived farming communities, one in Odisha’s Banki in Mukundpur village, and another in Gujarat’s Chitral village, in Vadodara district. CoolCrop constructed a cold storage in each of these centres. The third one at Vadodara was built a few months ago.

In Banki, Pravat Kumar Nayak, a social activist, facilitated the construction of a mini cold storage for a Farmer Producer Company (FPC) called Sakshyam. The facility stores multi crops.

Nayak says three farmers of the FPC, Saratchandra Behera, Maheswar Nayak and Koshalchandra Mohapatra, took full advantage of the cold storage. “The farmers stored four tonnes of pumpkin for three months and earned an additional income of Rs 12,000,” says Nayak. Storage of cauliflower and potato helped them earn a profit of Rs 13,000. In short, the cold storage increased their bargaining power.”

“For any mini cold storage to be financially viable it should store at least 10 to 15 tonnes of vegetables in phases for six to seven months, if not for the whole year,” says Marathe.

A five-tonne mini cold storage running on grid costs Rs 4.5 to `5 lakh to build. Cost of construction doubles if it runs entirely on solar power. CoolCrop’s cold storages have control modules that can be programmed and monitored with an Android phone. Marathe says their patented controller saves around 20 to 25 percent of electricity. “This is a marketing edge for us, over conventional cold storage systems,” he says. Energy consumption for a five-tonne cold storage would be around 10 to 12 units per day for 24 hours, when full.

Another customer-friendly feature is the use of Poly Urethane Foam (PUF) panels that make the cold storage modular. After a few years of use, if the capacity of the cold storage proves inadequate, its area can be easily extended by dismantling and restructuring the PUF panels. So creation of more space does not increase costs very much. For example, if a three metric tonne cold storage costs Rs 3.5 lakh, an upgradation to 10 metric tonnes will work out to only `6 lakh.

To help farmers take the right decision on when to sell, CoolCrop has invented a software which is still at an experimental stage that predicts the prices of crops for the next 15 to 30 days.

CoolCrop’s tracking module keeps tabs on crops inside the cold storage. It informs farmers when the quality of their produce is about to change, how long it can be stored and cooling energy consumed. It alerts the user if their produce is not in an idyllic environment. Both the market information facility and crop management platform are apps that can be downloaded on a mobile phone.

It wasn’t as if the villagers had demanded a cold storage facility. CoolCrop took the initiative and since all three cold storages were pilot projects, the company did not charge the villagers anything.

A grant they had painstakingly obtained from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Expo Live Dubai, enabled them to bear the Rs 12 lakh cost of the pilot projects.

CoolCrop met its own expenses of travel and incidental expenditure, like processing their proposals and travelling to Dubai to submit their presentation to the two agencies supporting them.

Storage gaps: India has huge cold storages of 1,000 to 2,000 tonne capacity, all in big cities and owned by big traders and farmers. They charge Rs 1 to 2 per kg per day. Small and medium farmers can’t dream of storing their produce in them. In fact, storages don’t even exist in areas where there is a lot of fruit and vegetable wastage. The best example is tomato-growing. But even onion, brinjal, cucumber, chillies, lemons and jackfruit suffer from lack of storage facilities.

Not that India is bereft of small cold storages. There are ones with five to 10 metric tonne capacity. But these are generally constructed and used by ice-cream companies or dairy companies. Small-scale cold storages exclusively for fruits and vegetables aren’t made. CoolCrop is filling in the lacunae with its inventively designed mini cold storages ideal for villages.

Marathe says it’s a tragedy that states which produce large quantities of vegetables just let them go to waste. Odisha, for example, produces a huge amount of tomatoes during the season. But after March and April, Odisha has no tomatoes. People wait for tomatoes to arrive all the way from Karnataka. The same farmers who offloaded their tomatoes during the peak season for as little as Rs 5 or Rs 6 per kg pay as much as Rs 25 to buy a kilo of tomatoes during the off-season. While cold storages can correct such market distortions, Marathe says it’s also important for farmers to plan production and diversify into agro-processing aided by cold storage facilities.

Transport too hikes costs for farmers. According to CoolCrop’s data, farmers in Bihar and West Bengal pay as much as Rs 1 to Rs 2.5 per kilo of produce for transport since these are perishable crops and need to reach markets quickly.

“If there is an aggregation facility like a cold storage in the village, transport expenses can be minimised. We want to establish cold storages as a critical part of the agricultural chain,” says Marathe.

He suggests that groups of farmers in rural areas opt for a mini cold storage of three, five or 10 metric tonne capacity. After two years, if they use it and need more space they can easily extend it for a modest sum.

“Our product will not immediately bring big money to farmers. But over a period of time it can help them gain more money if used judiciously. A five to 10 metric tonne cold storage, if used for a minimum period of seven months in a year, will pay back in three and a half to four years,” he says.

Marathe explained what he meant by judicious use. “Taking advantage of a cold storage facility isn’t just about storing your crops for a few months and selling it later. Farmers have to be innovative in crop selection. They must grow high-value crops instead of sticking to traditional crops. They should also be able to make good decisions on when to market their stored crops,” he says.

Business model: CoolCrop is now focusing on generating revenue from the cold storage projects it plans to construct. Marathe is keen to switch to a for-profit model. “We won’t build more cold storages using grants. They tend to be unsustainable. The stakeholder community doesn’t own the facility and there is no motivation to make the project viable,” he explains.

In July 2018, CoolCrop received the prestigious Challenge for Change award from the Rajasthan government. The award brought them orders worth Rs 25 lakh. The initial cold storages or technical pilot projects gave CoolCrop valuable insight on how to proceed further.

From now on Marathe and his colleagues have decided to construct cold storages on service-mode rather than on a profit-sharing basis. The company will instal the cold storage with a partner, either a local NGO, an FPO or a government agency. Social motivation, regular operations, paying electricity bills and general upkeep will be the responsibility of the local partner who will pay CoolCrop a prefixed rent on a per kg basis of crop stored. On an average, charges will be around 20 paise per kg per day. The partner will also facilitate technology adoption, inspire farmers to grow high-value crops and create awareness about marketing.

“At Joida, we wanted to help farmers figure out what is best. But we can’t force them to grow capsicum to use the cold storage and get very high returns,” says Marathe. “We are solution providers. Infrastructure alone isn’t enough. After installing five cold storages, we are aware of our limitations. For a project to be successful, creating the right partnership and operational model is as important as technological intervention.”

CoolCrop now has 10 confirmed orders for cold storages. Two are for the Tata Trusts in Gujarat, two for the Bihar Agri Growth and Reform Initiative and six for the Rajasthan government which is offering 50 percent subsidy for cold storage structures. Proposals for 15 more cold storages in eastern India — in West Bengal, Sikkim and Odisha — are under process.

“Agriculture has also to be seen as part of business. Just because you inherit land you don’t have to become a farmer. You need to have decent savings at the end of the day,” says Marathe who believes cold storage facilities can be a tool to increase, even double, farmers’ income.

In the next five years, Marathe’s target is to instal 500 cold storages all over the country. “Even if we achieve 200, that’s not bad. You can’t work unless you are an optimist. We have to take every failure as a lesson,” he says.

Contact : Niraj Marathe – 99727 67937; niraj@coolcrop.in

Comments

-

V saibaba - Dec. 1, 2019, 2:52 p.m.

A good attempt.Useful for many tribal villages