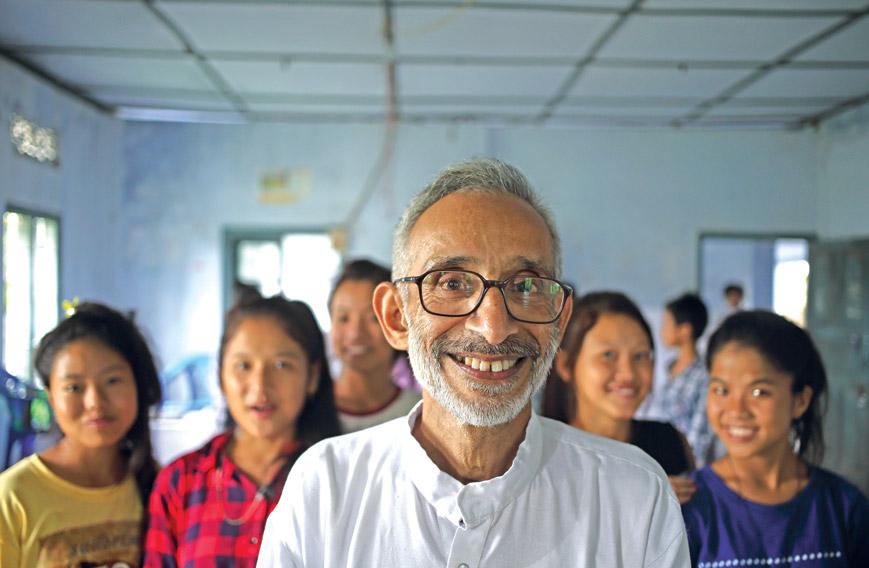

Sathyanarayanan Mundayoor, who is Uncle Moosa to his library volunteers in Arunachal Pradesh

Sathyanarayanan Mundayoor

There are many surprising things about Sathyanarayanan Mudayoor aka Uncle Moosa and often just Uncle Sir to many. First is that he is a Malayali who has spent his life with the tribal people of Arunachal Pradesh. Second is his frail bird-like presence and frugal subsistence - he literally carries his world with him as he goes from home to hostel in Arunachal's towns and beautiful villages. Third is the lasting impact he has had on educating and empowering girls and boys through his Lohit Youth Library Network, which serves to promote books and a sense of community at the same time.

Small libraries at remote locations reach deep into Arunachal where rivers and valleys make access difficult. So, the smaller and more distributed the better. Often, the books go home in search of readers uch as the Bamboosa Library in Tezu where a new building has just been inaugurated. There are also the libraries at schools.

A library comes with many possibilities. It provides opportunities for bonding, book-reading sessions, enacting of small plays. It helps young people discover themselves and grow in confidence.

Uncle Moosa arrived in Arunachal as a young man in 1979 to work at one of the schools run by the Vivekananda Kendra. In 1998 he decided to grow the libraries as a social movement. The libraries are supported by donors and the books too are donated.

Below is a piece that appeared in Civil Society's September-October 2016 edition. Read on.

Whether it was because of a Malayali fascination with the Himalayas or just a young man’s urge to do something different and exciting with his life, Sathyanarayanan Mundayoor turned up in Arunachal Pradesh in 1979 and never went back. You could say it was his destiny.

Now 65 years old and known as Uncle Moosa (and sometimes Uncle Sir), he is the cheerful inspiration for the Lohit Youth Library Network, which is a special effort to promote books and a sense of community at the same time.

Schools, such as those run by the Vivekananda Kendra where he was employed, had libraries. But in 1998 Uncle Moosa decided to place them in the midst of communities so that they could be vibrant and impactful in ways beyond the dictates of a school’s curriculum.

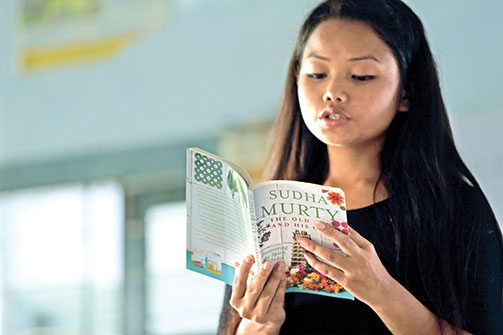

Young tribal girls and boys could then discover not just the joy of reading but also learn to express themselves though storytelling, staging skits and recitation. In addition, the libraries could create social awareness with special programmes on Women’s Day, Environment Day, Forest Day and so on.

The first community library was set up at Etalin in the upper reaches of the Dibang Valley. The Etalin library wound up in two years and the library network grew in Lohit district, which has in recent times been split into three separate districts. There are now 13 libraries — some dormant, some active, some in between. Resources are short and so these are mostly small setups with a limited number of books and periodicals.

It is not necessary for them to be large. The library network is meant to reach out to villages and towns that dot Arunachal across the rambling and diverse topography of the state. Small works better in such conditions. Different parts of Arunachal are often not readily accessible to each other. There are rivers and valleys and other natural boundaries to be crossed. It is a jigsaw of settlements and the library network’s relevance depends on being in many pieces and engaging intimately with clusters of users, at times reaching them in their homes instead of bringing them to the books.

The libraries are modestly funded through donations made to the Vivekananda Trust based in Mysore. Books also come from donors. When the Bamboosa Library opened in Tezu, the headquarters of Lohit district in 2007, it received 1,000 books from Delhi thanks to the Association of Writers and Illustrators for Children (AWIC). It also received books from America — which is why Roald Dahl is a big favourite in Arunachal.

At the Calsom Library in Tezu: Uncle Moosa flanked by Rejum Potom and Etalo Mega with enthusiastic student reader-activists

The Bamboosa Library had a biggish presence in Tezu, but the building that housed it was quite suddenly given to a hospital project. A new building is coming up for the Bamboosa Library and in the meantime the books have had to be stashed away at different locations.

The Calsom Library at Tezu is located at the Calsom School. It is a single room with books on shelves and in cupboards. Sukre Tamang is in charge and is helped by Rejum Potom, who is a teacher. Students in uniform are present when we arrive. Some are reader-activists of the library network and some have been brought from nearby schools to be present only because we are there.

Uncle Moosa addresses the students, switching between Hindi and English, and uses the occasion to fete the students who have been reader-activists.

There is special recognition for Etalo Mega, who spent seven years as a volunteer looking after the Bamboosa Library. Uncle Moosa has a cheque of Rs 8,000 for him by way of an award provided by a donor. Etalo currently has a government job in the Department of Gazetteers in Itanagar, the capital of Arunachal Pradesh. He has travelled to Tezu from Itanagar to meet us and receive the award.

There is special recognition for Etalo Mega, who spent seven years as a volunteer looking after the Bamboosa Library. Uncle Moosa has a cheque of Rs 8,000 for him by way of an award provided by a donor. Etalo currently has a government job in the Department of Gazetteers in Itanagar, the capital of Arunachal Pradesh. He has travelled to Tezu from Itanagar to meet us and receive the award.

There is also a library at Wakro, another small city in Lohit district. Reader-activists for this library come from two private schools, which are up to Class 8. The students then mostly go to Tezu to complete their schooling. Since the students keep moving on, the number of reader-activists fluctuates. There were 12 till last year and now there are around six.

Since 2011, the library at Wakro, in the interiors of Lohit district, has been experimenting with setting up mini libraries at the village level by allowing children to take home books during the holidays to lend them further.

LIBRARY FOR LATHAO

At the village of Lathao, in the newly formed Namsai district, a new library has been added to the network. It is reason to celebrate and the inauguration takes place during our visit. There are presentations and speeches followed by lunch.

Principal T. Ete (centre holding flowers) has provided a building at his school for the Lathao Library

T. Ete, principal of the Lathao Government Higher Secondary School, has generously set aside a small building for the library. Konchiwa Namchoon, a junior teacher, will be in charge of the library. The building used to be staff quarters and was to be demolished. It will now house the library, which earlier had just a little space inside the school and couldn’t function very well.

It is at Lathao that we meet reader-activists from Wakro and Tezu who have specially made the trip by bus. They are mostly young girls close to completing school. They have been exposed to a range of books from biographies to fiction to fantasies. But the big attraction of the libraries is the opportunity they offer for self-expression by way of storytelling, book-readings and staging of skits.

A frail, bird-like presence with bright eyes and a gentle yet energetic manner, Uncle Moosa’s goal has been to create an enduring library culture in Arunachal Pradesh. As he ages, he is eager the library movement finds ownership in the communities it has tried to serve.

“I tell people they will have to make the effort to keep the libraries going. They have to take interest and do the work. I can at best provide advice and support,” he says.

THE JOURNEY

Former students whom he has known for more than three decades already make a significant contribution. Some of them are teachers. At least one has her own a school. Uncle Moosa has been a life coach to them from the time they were children in the Vivekananda Kendra Vidyalayas. As the years have passed, they have become his extended family. The library movement draws and thrives on such bonding.

Sathyanarayanan Mundayoor went to Arunachal Pradesh as a ‘life worker’ for the Vivekananda Kendra, which had opened schools to help tribal children get a standard education and learn Hindi.

The schools were meant to give children in Arunachal a sense of their place in modern India. They would learn about the Indian Union, freedom struggle, Indian history and the contributions of Indian thinkers and political leaders. It was especially important to do so after the Chinese invasion of 1962 and the territorial claims made on Arunachal and the military conflicts of 1965 and 1972.

Solina Khambrai of the Bamboosa Library explains how reader-activists reach out

The Vivekananda Kendra’s initiative reflected the size and diversity of India. The kendra was headquartered at Kanyakumari, the southernmost tip of India and it was reaching out to Arunachal Pradesh at the other extremity of the country on the border with China.

The kendra advertised for ‘life workers’ and teachers ready to live in Arunachal and work in its schools. Sathyanarayanan Mundayoor, then 25 years old, was immediately interested. He knew nothing about Arunachal and was nowhere near being the Uncle Moosa he is today. And yet he desperately wanted to go.

“I don’t know if it was because of the kind of fascination my generation of Malayalis had for the Himalayas or whether it was because I wanted to do something completely different. But I felt this was something I wanted to do and so I applied,” he recalls.

He was at that time working as an income-tax inspector in Bombay. It was a secure job but not the life for him because he was a man of many parts. He had a bachelor’s degree in the sciences and was working on a master’s in linguistics. He enjoyed reading widely and had a keen interest in Malayalam and English.

He belonged to Thrissur but had spent his childhood hopping towns in Kerala because of his father’s transferable bank job. Employment in the income-tax department brought stability, but what he wanted was to break free and discover the world.

It is a decision, he says, he has never regretted. Arunachal is beautiful and its people are gentle and caring. He has sisters and brothers of his own in Chennai and Thrissur, who are always there for him and send him money. But Arunachal is where he belongs as Uncle Moosa, who is loved and welcomed into innumerable homes.

The Vivekananda Kendra recruited the young Sathyanarayanan as a ‘life worker’. He needed two years to complete his master’s in linguistics in Bombay and after that it was Arunachal for him. He went from ‘life worker’ to teacher and then education officer.

The difference that education can make to a generation is seen in Arunachal. It is a strongly patriarchal tribal society, but the girls who went to the Vivekananda Kendra Vidyalaya at Tafragram have all gone on to be achievers. They are now in their late thirties now, mostly married with children of their own, but working and earning.

At Timita Mungyak’s beautiful bamboo and wood house at Lathao children run happily and noisily through the rooms. This is the family home where her mother-in-law lives.

Nomita Lungchang and Sheelawati Monlai recall the time they were children together in the boarding at the Tafragram school. They remember Uncle Moosa as a young man. Today he stays over in their homes and they take care of him as they would an elder.

Timita has a master’s degree and teaches English in the government secondary school at Namsai. Nomita has a Ph.D in veterinary science and Sheelawati a Ph.D in botany.

Sailu Bellai was with them at Tafragram. So were Bapenlu Kri and Ibulu Tayang. We meet these women in Tezu. They belong to the same batch and know each other well.

Sailu became a teacher in the Vivekananda Kendriya Vidyalaya but set up her own school because she couldn’t take a transfer out of Tezu.

Bapenlu Kri works for the government as a deputy director in the department of urban development and housing. Ibulu Tayang is in the agriculture department as a training assistant.

They seem to share a spirit of voluntarism, which expresses itself in the Alumni Education Society and the Kun-Ta-Nau Welfare Society.

Ealto Mega was a young man when he joined the Bamboosa Library as it opened in 2007 in Tezu. “Uncle Moosa had a completely different idea of how a library should function. He told me that books have to be reached to children so that they become interested. We soon began visiting remote village schools, taking them books and organising events like recitations and book readings with them.”

Uncle Moosa is the name Sathyanarayanan Mundayoor took when he began writing a column for children in a local newspaper. As names go, it has a comic book quality about it and has stuck. Despite old-age infirmities such as his failing eyesight and weak back, the infectious enthusiasm and idealism with which he arrived in Arunachal hasn’t diminished.

Girls sing a Mishmi song at the Calsom Library

Umesh Anand and Photographer Lakshman Anand

Comments

-

DR BALAGOPALAN UNNI - Nov. 25, 2021, 11:24 a.m.

Great job by him and very well deserved for Padmashri. I am proud to be from the same village where he hails.Such people are very rare and our country needs such people My very hearty congratulations

-

Krishnan KR - Feb. 19, 2020, 3:57 p.m.

Very good naration about Satyanarayanan Mundayur who got Padmasree award 2019...