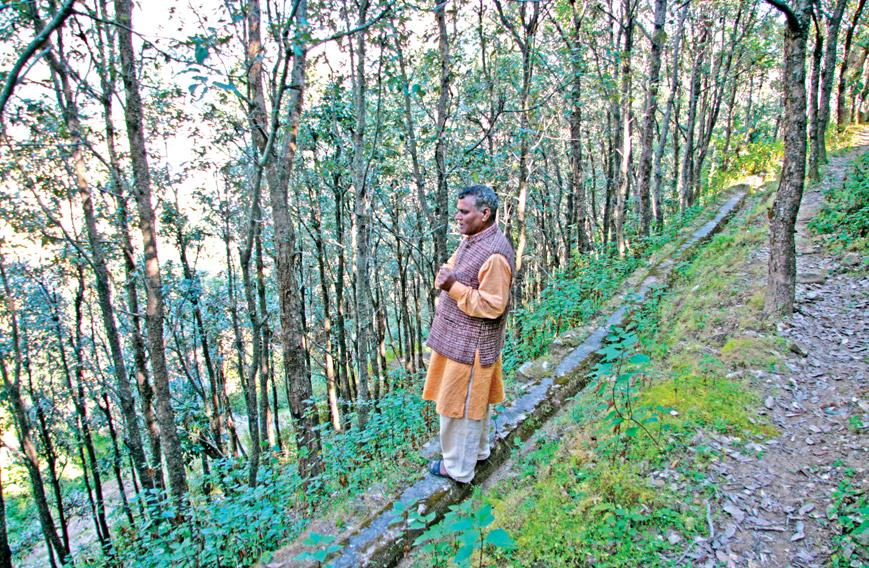

Sachidanand Bharati in Ufrainkhal's dense and moisture rich forest

People's Forester

When forest fires ravaged the hills of Uttarakhand one vast stretch went unscathed. This is Ufrainkhal where communities have grown local species of trees, sculpted traditional water bodies and revived a rivulet.

Ufrainkhal’s forests are dense with the majestic silver oak and wispy khair trees with deep roots that trap water. The ground below the canopy of trees is thick with humus, the hillsides dotted with small water bodies called chaals.

“Ufrainkhal’s damp forests and broad-leaved trees aren’t vulnerable to fire,” says Sachidanand Bharati. He has been the driving force behind the community effort that has combined traditional water sources with trees to make hillsides sustainable.

All over Uttarakhand, pine and eucalyptus trees are planted because those species are commercially valuable. But they impinge on groundwater and do nothing for the village economy. The forest department owns almost all the forests in the state and grows pine widely.

“In Uttarakhand, people don’t feel connected to forests anymore. They think its the duty of the forest department. If there is a fire they don’t rush in to stamp it out,” says Bharati.

Bharati and his small group, the Doodhatali Lok Vikas Sansthan, began galvanising villagers in Ufrainkhal in Pauri Garhwal district 35 years ago.

Devi Dayal, Dinesh and Vikram Singh: the postman, the Ayurveda doctor and the shopkeeper who have campaigned with Bharati

His three spirited comrades who played a lead role in this turnaround are Devi Dayal, a postman, Dinesh, an Ayurvedic practitioner and Vikram Singh, a grocery shop owner.

Bharati teaches in the Ufrainkhal Inter College. In 1982 he returned to Ufrainkhal from Chamoli district after taking part in the Chipko (hug the trees) movement. To prevent their trees from being cut by a contractor anointed by the government, Chamoli’s women hugged them. The movement remains a symbol of forest conservation and peaceful resistance.

Bharati came back to find the same sorry tale of destruction being repeated in his own village. The forest department had just granted fresh logging leases in the forests around Ufrainkhal.

Determined to stop this mindless destruction Bharati and his friends went from village to village telling people to resist. The people listened. They knew that the ancient trees standing in their forests were invaluable.

Backed by them, Bharati reasoned with forest department officials. He persuaded them to come and see the value of old forests.

When the officials saw the forests they had to agree with Bharati. The logging leases were scrapped and the trees survived.

The villagers had won a quiet victory. It struck them if they spoke in one voice they could persuade the government to rescind ecologically disastrous orders. They could work as one to restore the pristine environment they once had, they thought.

So in July 1980 Bharati held a two-day environment camp in the Doodhatoli mountains and invited all the surrounding villages to Ufrainkhal. In those years, the focus was on planting seedlings and saplings and putting back the trees that had been lost.

It was in March 1982 that Bharati founded the Doodhatoli Lok Vikas Sansthan to replant forests. His small people’s organisation had no money, no employees not even a signboard. Devi Dayal, Dinesh and Vikram Singh were its first three members.

Devi Dayal the postman treks from village to village and door to door delivering letters and money orders. There aren’t any cars or buses here, not even roads for a bike. He is the organisation’s eyes and ears for he observes the forests on his rounds and delivers messages of forest and water conservation along with the mail.

Dinesh, the Ayurveda medical practitioner, listens to a range of people who approach him for medical advice. Dinesh examines them, prescribes medicine and dispenses ecological and social messages together with his medicines.

Vikram Singh runs a small kirana store in a neighbouring village. It is here that people congregate to gossip and exchange notes. Vikram veers the conversation to ecology.

Bharati realised that culture was a powerful means of communicating. Local hill culture is steeped in ballads and stories about jungles, animals and water. Bharati has a small troupe that winds its way from village to village, from Daund, to Dulmot to Jandriya — singing songs with local musical instruments that tell people to slow down water gushing down the hills, hold the soil together with trees, restore the forests and revive their small terrace farms.

In a region where men migrate en masse for employment a group of 15 girls sing this lyric: ‘The water in the springs of my hills is cool. Do not migrate from this land, O my beloved.’

At Daund, despite the rain, villagers, mostly women young and old, sit around and listen. The village is small and perched 6,000 feet above sea level. The villagers know the rain will collect in a stream and tumble down the hill. It will join the Ramganga river and the silted water will make its way to the Corbett National Park.

This symbiosis of culture and ecology helps people to rediscover their roots, their traditional respect for nature. It brings the village together and creates an ambience that encourages them to restore the environment that sustains them.

SETTING UP NURSERIES

In those days the forest department would hand out saplings of trees that were commercially important like pine, valued for resin, or eucalyptus valued for its oil. But such trees didn’t help the women.

As forests depleted, women trekked further and further away to gather firewood, fodder and herbs, sometimes walking 8-10 km a day. “If a woman is stressed and unhappy, the family is unhappy,” says Bharati.

He reckoned if he could bring the forest closer to the women he would ease their burden. “I thought could I reduce their distance to one or two kilometres? So we began looking at degraded land in the village and reforesting it.”

But they needed seeds and saplings of trees and plants useful for the women, the indigenous varieties. Bharati’s group had to set up their own nurseries. Women and children were drafted for the job of collecting seeds.

Then they hit a wall: they didn’t have water. The nurseries needed water especially in summer when the seeds germinated. So did reforestation. But Ufrainkhal faced a scarcity of water. In trying to resolve this problem Bharati began searching for solutions.

The answer lay in the village’s name. Ufrain is the name of a goddess. Many villages and towns in Uttarakhand have either a taal, khaal or chaal as part of their name. These are water bodies of different sizes and villages and towns came up around them. Bharati learnt all this in a book he read.

But with no khaal in Ufrainkhal, Bharati and his group decided to experiment with the chaal. It seemed perfect for Ufrainkhal’s steep slopes. It was small so it would hold some water and it wasn’t big enough to cause a landslip.

For a while the Doodhatoli group experimented with various shapes and sizes of chaals in the early 1990s. Soon, they found the right design, the perfect fit for their forests.

From 1993 to 1998, Bharati and his group began digging chaals along hill slopes. Just a year later after the rains water began flowing in a rivulet called Sukharaula, which had been dry for decades. It stayed for a few months. The next year, water stayed for a longer duration. By 2001 the Sukharaula became a full-fledged river.

A view of the forests of Ufrainkhal

Bharati’s group has built 12,000 chaals in 136 villages till date. Trees like oak, rhododendron, fir and alder populate the forests. Several patches are very dense and biodiverse. In fact, Ufrainkhal’s forests are better than the government’s reserved forests administered by the forest department.

ROLE OF WOMEN

Women from 150 villages are involved in forest conservation and protection. The Doodhatali group maintains regular communication with about two dozen volunteers, mostly women, in each village for the men migrate to the plains for work.

The thousands of chaals built here and the hundreds of hectares of regenerated forests are their only hope. The women number in hundreds and are a silent green brigade.

They have devised an ingenious system for handing over forest protection duties to the next volunteer— typical of how the women here combine music and rhythm in daily chores.

The woman in charge of patrolling the forest carries a baton with a string of bells tied on top. The sound of the bells reverberates across the silence of the hills.

When a woman is done with her shift, she returns to the village and leaves the baton at the doorstep of a neighbour. Whoever finds the baton in front of her house takes up guard duties the following day.

Forest guards are not needed. The women play that role. Bharati’s group has formed hundreds of Mahila Mangal Dals across villages. “Everyone is equal in the group. There is no high caste or low caste, rich or poor,” says Bharati.

The Mahila Mangal Dals are evolving, venturing into microfinance for loans with modest interest: Rs 1 for every Rs 100 taken.

Bharati bridged the distance between women and forests. He believes if the distance between people and ecology is bridged, the result will be a greener environment.

Trees and paths in the forest

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!