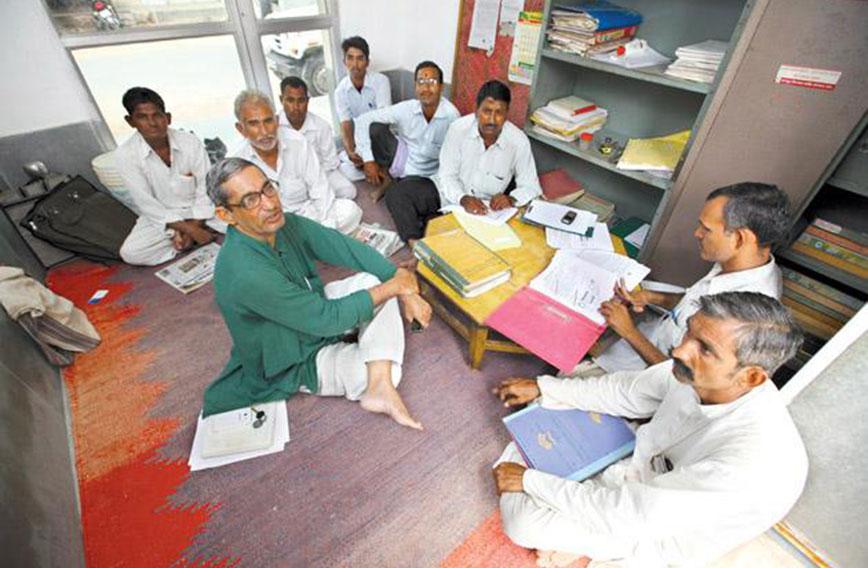

Chetan Ram in the centre and Rawat Ram, second from right, examining files at the Soochna Kendra | Lakshman Anand

Chetan Ram & Rawat Ram

If the ordinary man gets his due in Nokha in Rajasthan, it is because of the Soochna Kendra that Chetan Ram helped set up. Chetan Ram is the founder of Urmul Jyoti Sansthan and an old warhorse of the right to information movement. Chetan’s enthusiasm inspired Rawat Ram to join the Urmul Jyoti Sansthan in a full-time role.

At the Soochna Kendra, people come to file complaints and RTI applications. Making a law is not enough, the people must be empowered to use it. The Jagruk Nagrik Manch is an initiative to encourage people to become aware.

Sometimes, people come to the Soochna Kendra to seek help for filling a form correctly. This is not an insignificant role. Raj Kanwar, a widow, managed to send her son to school because the Soochna Kendra helped her fill out the relevant forms.

The common man often feels helpless when faced with the state machinery. The Soochna Kendra helps him navigate it. The Kendra is also a repository of information on the benefits available for widows, people with disabilities, pensioners and below poverty line citizens. The duo’s work makes sure that the people of Nokha know of and exercise their rights.

Implementation of RTI at the grassroots depends on activists like Chetan and Rawat. Similarly spreading digital access means being available when people who have never seen a computer and can't read or write need the government system to to work for them.

Below is a piece that appeared in Civil Society's September-October 2013 edition. Read on.

When the film star Dharmendra was elected to the Lok Sabha as a BJP candidate from the Bikaner seat in Rajasthan in 2004, his campaign speeches consisted of famous lines from his films. He had the constituency charmed. But he did nothing for five years and angry voters vowed never to let him enter Bikaner again!

Rawat Ram tells us the story with a slight laugh in his soft voice as we wait at the Nokha railway station for a train back to Delhi. He is a polite man, dressed simply and with very few needs. He makes no dramatic statements and yet he is every bit a hero – that too in real life.

From a tiny Soochna Kendra of the Jagruk Nagrik Manch in Nokha town, 60 km from Bikaner in the Thar desert, Rawat Ram helps people know about their rights and take on inefficiency and corruption in the government.

It is a challenging role that requires courage and persistence and diplomacy in no small measure. Rawat Ram is a natural at it.

The Soochna Kendra is the creation of the Urmul Jyoti Sansthan whose secretary Chetan Ram is an old warhorse of the right to information (RTI) movement. In the villages of the Nokha block, he has encouraged people to be 'jagruk nagrik' or aware citizens.

It was in this process that he met Rawat Ram, who decided to work full time with Urmul Jyoti and be mentored by Chetan Ram. The story of Mohan Lal is similar and, like Rawat Ram, he, too, plays an organising role.

The Soochna Kendra is a small room, perhaps 150 square feet. It was started in 2000 when the Rajasthan Right to Information Act was passed. Initially, the room was taken on rent. Later, Urmul Jyoti bought the premises. Slippers and shoes are taken off before entering and everyone sits on a rug that covers the floor. It is located near government offices that serve the Nokha block so that it is easy for people with problems to find assistance.

Not everything that the Soochna Kendra does is adversarial. Very often officials send villagers to the kendra so that applications are filled correctly. Sometimes a bribe has been paid, but the work has not been done. The kendra negotiates a settlement on behalf of the hapless citizen – getting the money back and the job completed without a formal complaint.

Says Chetan Ram: "Our location here next to government offices is important. At these offices you will see middlemen who offer to get things done for some money. People get taken in. Often they lose their money and end up with their records and title deeds falsified and misappropriated. The Soochna Kendra is the anti-thesis of these middlemen. From here we help people learn how to make the system work for them."

Noticeably, the kendra does not have a computer. But much has been packed into the small room. The kendra is surprisingly well informed and methodical. There are registers with the names of people who come to it for help – they run into a couple of thousand at least. A record is kept of complaints and the progress made in resolving them.

The kendra is also a repository of information on the benefits that should go to pensioners, the handicapped, below the poverty line persons, widows. There are useful lists: names of officers and Gram Sevaks, for instance. There is information on schools and anganwadis.

"It is because of the work of this kendra that the benefits received by people in the Nokha block are equal to those of the four other blocks in Bikaner district," says Chetan Ram.

The government also runs Soochna Kendras to help with implementation of RTI. But they are not successful. One reason for this is perhaps the lack of zeal. Ferreting out corruption and making a bureaucracy deliver results require passion and a sense of purpose.

Nokha's Soochna Kendra draws its energy from the Jagruk Nagrik Manch initiative. It delivers results because it is part of a larger vision.

The government has plans for replicating the Nokha Soochna Kendra elsewhere. But that will mean emulating the spirit in which it was created and finding a mentor like Chetan Ram or activists like Rawat Ram and Mohan Lal.

A day at the Nokha kendra gives some indication of its popularity and the different problems that it helps resolve.

As we sit down in the kendra and get talking, Raj Kanwar, a widow for the past five years, shyly makes her presence felt at the door. She has her ghunghat or veil in place and won't speak face to face with Rawat Ram or the other men in the room. She won't even enter the room.

As a widow she gets Rs 500 pension. For every child she sends to school, she gets Rs 625. Two of her boys are already in school. She now wants to admit the third, Ashok, who she has brought along.

When she approached the government department concerned she was sent to the Soochna Kendra to get the relevant forms and have them filled correctly. She doesn't have a complaint, but only needs help.

A lot of government money has poured into rural areas like Nokha. It has gone into guaranteed employment, pensions, incentives for educating children and so on. There have been investments in infrastructure too with village roads getting built.

With the inflow of money has come corruption. Panchayats have been siphoning off funds. Officials in government see an opportunity for commissions when people claim their entitlements.

Better access has made land more expensive. Remote as it is in the Thar desert, Nokha is seeing the first signs of a real estate boom because a bypass is apparently planned from Bikaner to the highway. The result is that developers have been buying land and selling plots for gated colonies.

As these changes take place, the greed for acquiring land in any which way possible is one dominant story. Records are being falsified and holdings sold off without the knowledge of the real owners. Cases abound of people being told suddenly that their houses and lands do not exist.

New laws like RTI empower citizens to fight back. It is possible to get out documents and open up files. But it is not easy and the Soochna Kendra plays an important role in handholding the individual.

Take the case of Joga Ram Garg of Panchu village. He found in 1990 that after a survey by the Settlement Department, 63 bighas belonging to his family was no longer shown as theirs in the map of the area. It had been included under government land designated for grazing.

In 1991-92, after much effort, he succeeded in filing a complaint with the Revenue Department, which said he should go to the Settlement Department, which said the land did not exist.

In 2005, he finally went to court. Filing case was one thing. Hetting justice quite another. He didn't have the documents on the basis of which the case could be argued. The Revenue Department and the Sub-divisional Magistrate also didn't have the documents.

It was only the Settlement Department that had the documents and it refused to accept Joga Ram’s application under RTI. The application was sent by registered post and yet there was no reply for 30 days.

He then went to the Appellate Settlement Commission in Jaipur. It sent a notice to the Settlement Department. Once more there was no response. Finally, the Chief Information Commissioner in Jaipur sent a notice to the Settlement Department in Bikaner.

At the end of this long process, Joga Ram received a reply this July saying that his family's 63 bighas and some other piece of land had been wrongly merged with 515 bighas of grazing land, inflating it to 584 bighas. Joga Ram's land is currently worth Rs 1.2 crores. It is a lot of money in these parts. Joga Ram would like to celebrate, but a cloud of doubt remains regarding when the record will be formally set right.

There are several other kinds of cases that the Jagruk Nagrik Manch takes up. They have to do with schools, health facilities, misuse of railway staff accommodation, ration shops and even the location of electricity poles. One of the applications has unearthed the siphoning off of Rs 36 lakhs meant to have been distributed under the rural employment guarantee scheme.

Having laws that require governments to be transparent and accountable is a big thing. However, empowering people to use such laws requires a social movement.

The Urmul Jyoti Sansthan has tried building a can-do mood in the villages of Nokha. It has an innovative programme for getting back bribes. So far Rs 70 lakhs have been returned, says Chetan Ram. The trust helps girls get an education and reaches out to the elderly. There is a facility for eyecare where cataracts are also removed and glasses dispensed.

Multiple associations bring people closer to the Urmul Jyoti Sansthan. Involvement with the Jagruk Nagrik Manch then comes quite easily. Members of the manch now have identity cards and proudly talk about the RTI applications they file. Perceptions change and here far in the desert with any number of problems to contend with people have begun to see the impossible as possible.

Umesh Anand saw the Soochna Kendra at work

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!