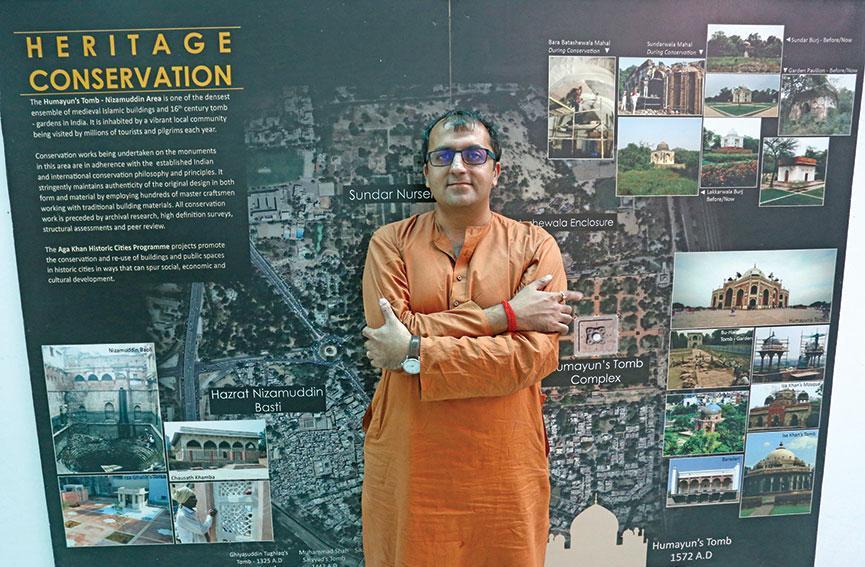

Ratish Nanda

Humayun’s tomb and other monuments in the Nizamuddin area of Delhi have been elaborately restored in an effort that would do any world-class city proud.

It has taken all of 15 years, but the historic structures, together with their gardens and water systems, have been uniquely brought back to life.

The Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC) has collaborated with the Indian government for this initiative. There has been private sector funding as well. But driving the idea and brilliantly making everything happen has been the public-spirited architect Ratish Nanda.

Nanda has led a team of diverse modern talents. He has also ferreted out traditional craftsmen. Jointly they have recreated long-lost nuances in construction techniques and design. Nanda has shown entrepreneurial resolve in getting government permissions, raising funds and garnering social support.

Nizamuddin is the cradle of Hindustani culture. Its architecture, food, music and poetry speak of India’s inherent pluralism. You will find Mirza Ghalib’s tomb here. But the Nizamuddin basti over time had become a crumbling slum. The project has brought to the basti education, livelihoods, better sanitation and healthcare. It has thereby taken conservation into the complex terrain of urban renewal. “We see conservation as a tool. It is not an end in itself,” says Nanda.

Civil Society has tracked Nanda's work over the years. Below is a piece that appeared in the edition of January 2013. Read on.

Also read an exclusive interview with Ratish Nanda here: https://www.civilsocietyonline.com/interviews/urban-heritage-should-have-wide-ownership/

A few hundred metres from the crazy traffic in the Nizamuddin area on Mathura Road emblems of Delhi’s heritage have been coming to life. It is a revival with many facets: in architecture, design, music, craftsmanship, gardens, water systems, urban planning, colours and cuisine.

Monuments have been restored with rare passion and creative skills. Old landscapes have been rediscovered. Structures lost to decades of neglect are visible once again, their perfections intact. Indigenous species of trees have been brought back in thousands.

An evening of qawwali music in the courtyard of the Chausath Khamba in the Nizamuddin Basti proves to be magical. A visit to the garden tomb of the Mughal Emperor Humayun is dizzying for all the detail in design and structure that restoration has put back in place.

Humayun’s tomb belongs in the tradition of being laid to rest in a garden paradise. Babur, the first Mughal emperor, began the tradition. Humayun’s tomb, commissioned in 1562 by his widow, turned out to be much grander than the Bagh-e-Babur in Kabul.

But far beyond what one can touch, see and smell, the restoration also explores the bigger zone of a mystical paradigm: the renewal of identity and spirit.

The Nizamuddin Basti, or settlement, is where Hindustani culture began. So, this is much more than an archaeological restoration. It is a rebirth in an original cradle – a wow moment. Circumstances don’t often conspire to such perfection.

The dargah or shrine of the Sufi saint, Hazrat Nizamuddin, is in the Nizamuddin Basti. His favourite disciple was Amir Khusrau, the qawwali exponent and originator of Khari Boli, the Hindi we speak today. He, too, is buried here. So is the legendary poet Mirza Ghalib.

Delhi’s only surviving stepwell, the Nizamuddin Baoli, built in 1321-22 is adjacent to the dargah. The crumbling buildings surrounding the baoli and waste disposed of by pilgrims have dirtied its waters. But the waters continue to be replenished mysteriously by underground springs!

The Nizamuddin Basti sits on 700 years of such significant and captivating history and includes the largest collection of valuable Islamic buildings in India.

The basti’s exclusion from Lutyen’s Delhi and its current poverty and decaying infrastructure make it difficult to believe that it had a glorious past. But the basti was once the original urban heart of Delhi with an evolved secular tradition and tolerance of different cultures. As a trading centre it was prosperous too.

Reviving the Nizamuddin Basti, therefore, is a task that has much contemporary relevance. The inclusive and inter-cultural values associated with the basti in its heyday are even more relevant now. Also, the strategic midwifery that delivers new civic facilities in the basti could be the inspiration for overcoming similar challenges in the old quarters of other Indian cities.

The present conservation and urban revival effort is led by the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), which works through its arms, the Aga Khan Foundation (AKF) and the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC).

A memorandum of understanding was signed in 2007 involving the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) and the Central Public Works Department (CPWD). A subsequent MoU was signed with the Delhi Development Authority (DDA).

There are multiple buy-ins at various levels. For instance, the personal involvement of the local municipal councillor, Farhad Suri, has been invaluable.

The project gets financial support from the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust, Sir Ratan Tata Trust, Ford Foundation, US Ambassador’s Fund for Cultural Preservation, World Monuments Fund, German Embassy and HUDCO.

Earlier, in 1997, the Aga Khan had funded the restoration of the gardens around Humayun’s tomb as a gift to India on the 50th anniversary of its Independence.

But the current project is envisaged to run much deeper. It is an urban renewal initiative, which goes beyond architecture. It includes the Nizamuddin Basti in the belief that conservation should generate livelihoods and make meaningful improvements in the way ordinary folks live. It is not enough to bring back monuments. The community must be involved.

Says Ratish Nanda, project director, “The restoration of the gardens at Humayun’s tomb was seen as a successful PPP venture. But His Highness the Aga Khan wasn’t satisfied because people hadn’t benefitted.”

“We looked for projects in Hyderabad and Agra and came back here because of the possibility of linking conservation with major socio-economic development. Its central location helps us create a visible model,” says Nanda.

“We see conservation as a tool. It is not an end in itself,” he explains.

Nanda is supported by a multidisciplinary team of 172 people. He trained as an architect in Delhi and grew up in the city next to monuments without knowing their significance.

Inspired by a professor of his, he began looking at history and archaeology more closely. Now he is acknowledged as an expert with his own approach to restoration. He has worked on the restoration of the Bagh-e-Babur in Kabul.

But restoration draws on team effort, especially a project as complex as this one. Many hearts and minds have to be in unison. Nanda leads a pool of talented and highly qualified people who hang together because they share a mission though they come from different backgrounds.

The core team has Rajpal Singh, Jyotsna Lal, Guntej Bhushan, Sangeeta Bais, Shveta Mathur, Deeti Ray, Archana Saad Akhtar, Aftab Jalia and Somak Ghosh.

FROM DEPAIR TO HOPE

Over five years the benefits from the project have been many. It has provided employment, better health care and schooling. Homes have been renovated, some streets paved afresh and parks reclaimed for the use of the community.

The project has taken the basti from abject despair and decay to hope – though much remains to be done and it continues to be an urban hell for the families residing in small rooms in buildings built close together. Some of the lanes between buildings are barely wide enough for one person.

Recently, in the last week of November, the Apni Basti Mela, or fair, held over three days, brought residents out in large numbers in a carnival mood. Importantly, it was held in a park that used to be overrun by drug peddlers and criminals. So, some things have changed forever and the residents realize this.

For the city of Delhi as a whole the project has provided 152 acres of open green space, which is invaluable in the face of ever-increasing congestion. Interestingly, 41 acres have been taken back from other users and given to the ASI. Getting back land is normally an impossible task in any urban setting.

“This entire area is all gardens. Humayun’s tomb is contiguous to Purana Qilla, the Delhi Zoo, Sundar Nursery and the Millenium Park,” says Nanda. “This area, right in the middle of Delhi, would be bigger than Central Park. You can create a 1,500 acre city park if you make pedestrian connections and transport linkages.”

It was with Humayun’s tomb and other monuments and the adjacent Sundar Nursery that the project began.

SEARCH FOR PERFECTION

The challenges here were huge because Nanda, as project director, set out to raise the bar for what needed to be done. It was to be a restoration in the truest sense with materials and techniques similar to those used when the monuments were originally built.

It was decided to use lime mortar instead of cement for repairs. All colours for the patterns and designs were to be from natural dyes. Craftsmen were flown in from Uzbekistan to teach the art of making tiles.

A search was launched for Indian craftsmen who could do traditional work in stone. They were identified in their villages and brought to Delhi to recreate pieces of the structures that needed to be replaced.

It was also important to find stone that matched the original – not just in colour, but in grain and texture too. So, stone pieces had to be sourced from Rajasthan. Occasionally, the stone was found in the most unlikely of places. For instance, during the Commonwealth Games, when pavements were being dug up in Delhi, some of the discarded stones were perfect for the floor of the apron of Humayun’s tomb!

Creating a single piece of lattice can take weeks and months. Each stone is unique. Sizes vary, sometimes by very little. It means first getting the thickness of the stone slab right and then chiselling it to make it even. After that comes creation of the design, which, when there is lattice work involved, has to be the same on both sides.

The goal in conservation is to match a known original. In stonework a craftsman is often working on two planes and then creating fine ridges and curves. Detail and precision are required.

The project has so far generated some 100,000 man-days at Humayun’s tomb alone, which means that around 2,000 traditional craftsmen have been given employment. This is a signal achievement because it has created a demand for vanishing skills.

Attar Singh is one such craftsman. He is in his fifties and comes from Dolpur in Rajasthan. He does some of the really fine work at the project site.

Attar Singh is eager to explain some of the finer challenges of his craft. “It requires flexibility and precision because no two designs are the same,” he says.

He learnt from a master craftsman and has taught others, but the market for such work doesn’t exist. “My son doesn’t want to be a stone craftsman. He is studying to be a teacher in the village. It is like that with most of our children.”

SENSE OF WONDER

Restoration succeeds when it brings back the original splendour of the monument. “It must be such that the visitor is overwhelmed. We have to bring the ‘wow’ factor back,” says Nanda.

At Humayun’s tomb and the nearby tomb of Isa Khan the areas around have been restored to enhance the presence of the monuments.

At Humayun’s tomb, revival of the gardens in the earlier phase was crucial. Together with the gardens, water channels were restored. The slope of the channels allows the water to flow with gravity. It is a fine sight and water has a pleasing effect.

The outside and inside of the tomb have been worked on extensively with lime mortar replacing the cement clumsily used for repairs earlier.

“We have removed one million kilos of cement concrete from the roof of Humayun’s tomb and restored 200,000 square feet of lime plaster,” says Nanda.

And what happened to the one million kilos of cement concrete? Well, it went into building the peripheral road in Sundar Nursery. So, there was zero garbage.

Removing concrete from a monument is a delicate task. Cut too deep and the monument gets damaged. So, the project team sought international expertise. One of the proposals was to create very precise incisions with a diamond-edged tool. But just making the incision would cost Rs 86 lakhs. Instead, it was decided to employ traditional craftsmen using hand tools. The final bill: just Rs 5 lakhs!

Lime mortar was used traditionally before cement became popular. It works better because it breathes – allowing moisture to escape continuously over the years. Cement does the opposite: it locks in the moisture, which then damages the structure.

But it is lime punning that truly enhances the look of a monument. Lime punning is a thin coat of about one millimetre thickness consisting of lime, marble dust and other natural additives such as egg white.

The result is a smooth and pearly surface that brightens the inside of the tomb and offsets the colours in the designs on the ceiling. The effect is dramatic in the Humayun tomb, Isa Khan tomb and the Sundar Burj.

Punning also has to be red to match the original sandstone of the building. In this case powdered brick is used.

DIGGING UP THE EVIDENCE

Excavations have led to some major changes. For instance, at Isa Khan’s tomb it was discovered that four feet of mud had piled up, covering the base of the tomb and leaving only the upper portions of the arches in the inner wall showing.

Finally, 12,000 cubic metres of mud were removed to reveal an original layout in which gardens sloped away from the tomb as a tiered draining board for collecting rainwater. The apron of the tomb similarly sloped towards the gardens with spouts serving as points from which the rainwater could flow out.

With the mud removed, Isa’s tomb has been transformed. Lemon trees have been planted in the sloping gardens. When they reach their full size they will be at eye level for someone standing on the apron of the tomb.

SIMPLE AND EFFECTIVE

Sometimes effective renovations are simple moves based on how the contemporary eye visualises space and necessity. At the Chausath Khamba, a big wall divided it from its own forecourt beyond which was the Urs Mahal. The wall was removed and a spacious courtyard emerged. It is here that music festivals are held.

Mirza Ghalib’s grave is next to the Chausath Khamba. There was metal fencing between the grave and the road alongside. It was a jail-like ambience not befitting an historical site. The AKDN also wanted to hold mushairas or poetry sessions in honour of Ghalib at the grave. It was a great idea but a better atmosphere was needed. So, the severe metal grills were replaced with delicate stone lattice work which serves to keep out noise as well.

The Chausath Khamba is the tomb of Mirza Aziz Kokaltash. It is built entirely of marble with 64 marble pillars supporting 25 marble domes.

It is going through extensive renovation. Each stone in the roof is being removed, repaired, documented and replaced. As in the case of other monuments, earlier repairs using cement had caused extensive damage.

In the original construction of the Chausath Khamba, iron clamps were used to hold the stones together. With the cement used for early repair work trapping moisture in the structure, those iron clamps had been rusting. They are now being replaced with stainless steel clamps.

THE SUNDAR NURSERY

Sundar Nursery is being redeveloped to be a unique destination where nature lovers can go to learn more about plants and trees. There are some 13,000 parks in Delhi but not one offers this opportunity.

A survey done in 2007 showed that there were 1,800 trees with 146 species of plants and trees in Sundar Nursery. Since then 20,000 plants of more than 300 tree species have been introduced. Sundar Nursery has 27 rare species of trees not found in Delhi or the rest of India.

The emphasis, however, is on species native to Delhi. A special microhabitat zone – meant to serve as a microcosm of Delhi’s original landscape – spread across 12 acres within Sunder Nursery hosts over 92 species.

Sundar Nursery is being developed with a central axis. At one end is Humayun’s tomb at the other the Azimganj Sarai. It will have the form of a Persian garden with smaller water channels leading into a bigger water body.

An amphitheatre is being built and a location created for flower shows. In addition there will be revenue from a restaurant.

RELOCATING FAMILIES

In Nizamuddin Basti AKDN faces its chosen test of making conservation work for the social and economic uplift of people.

It hasn’t been easy because it means reaching out and establishing trust. Finally, people have to believe that things will work for them. They have to be part of the solution.

A truly big challenge for AKDN was to get 18 families to relocate from their crumbling homes atop the Nizamuddin Baoli.

The wall of the baoli had collapsed and needed to be urgently repaired and for this the families had to move out for good.

It took Shveta Mathur of the urban renewal unit months of talking to the families to finally get them to relocate to a resettlement colony.

“At first they wouldn’t let us into their homes. There was a narrow passage where they would stop us,” recalls Mathur.

But patience and gentle persuasion prevailed. Dealing with the government required as much persistence because it had to provide the land where the families could be resettled.

Finally, each family got just 12.5 square metres to build a house in a peripheral area of Delhi! But they moved on.

A topographical survey of the basti met with stiff resistance.

Seven principal streets were identified for improvement. These were the most densely used streets since they were entry points into the basti and led to important spiritual and heritage sites.

“Infrastructure was the turning point. Once residents saw street lights, roads and drains they got very interested,” says Mathur.

AKDN refurbishes homes by providing 40 per cent of the cost in the form of materials. If the head of a household is a woman, assistance is increased to 60 per cent. Around 95 houses have been repaired. A door-to-door garbage collection system has been started.

Public toilets have also been made. Families pay Rs 30 for a monthly card. For single use, Rs 2 is charged. A local self- help group (SHG), the Rehmat Nigraani Samooh, keeps the facility clean. A second toilet complex with bathing facilities is coming up.

“You know, we were always embarrassed about our neighbourhood. It was so dirty. My children used to say let’s go live somewhere else. Now we feel proud of our basti. Truthfully, we did not know each other. We got to meet thanks to AKDN,” says Zahida who has lived in Nizamuddin Basti for 30 years and is now a health worker with AKDN.

The municipal primary school has undergone a transformation. The walls have coloured tiles depicting nature. The school has incorporated Building as Learning Aid (BALA) techniques to make learning fun for children. There are rows of low blackboards for children to scribble on. Drinking water has also been placed low so that children can access it. There are measurement charts on the walls and floors. There are toilets and unbreakable glass windows.

Enrolment has shot up to 633 children, says Haider Rizwi, the education coordinator. A Vidyalaya Kalyan Samiti was started as an interface between parents and teachers. The problem was that the school had no system in place. There was no assembly or timetable.

“My 26-year-old son went from Class 1 to Class 5 without learning a thing,” says the elderly Jamila. “But my grandchildren are very smart. They know English, numbers, everything.”

AKDN assessed the health needs of residents with the community health department of AIIMS. Unsurprisingly, pregnant women and children emerged as the most vulnerable group. A path lab was set up where 32 types of tests are carried out and 55,000 have been done till date.

Forty local women have been trained as health workers or Sehat Sahelis. Each looks after 40 homes. They report to a Sehat Appa who in turn reports to the doctor or public health specialist.

Previously around 82 people used to approach the polyclinic every day. That number has doubled to 150 people. “Sehat Sahelis now report fewer maternal deaths and less malnourishment. Women are taken to hospitals for delivery,” says Dr Simran Wadhawan, a specialist in public health who supervises the outreach. Every health worker explains what foods to eat.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!