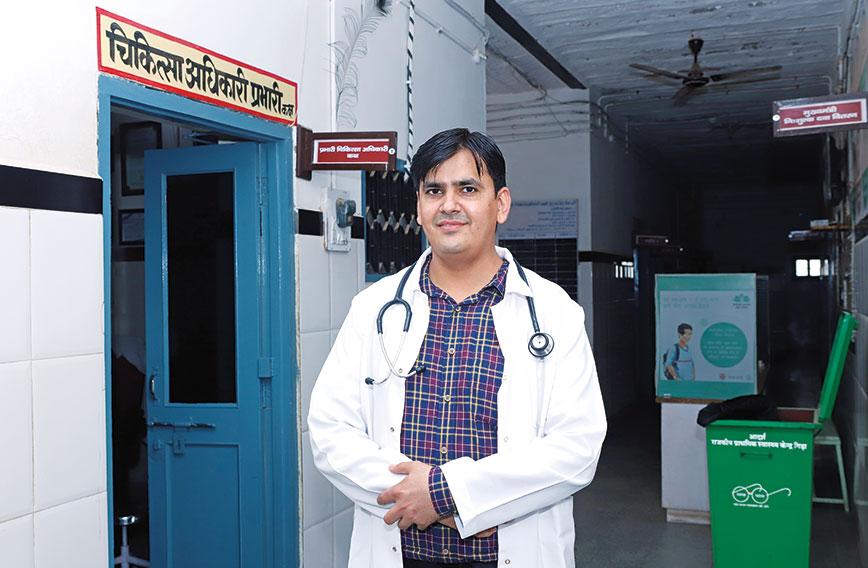

Dr Jogesh Kumar at the primary health centre

Jogesh Kumar

Most young doctors dislike working for the government health system in rural areas. But at the age of 25, Dr Jogesh Kumar embraced the challenge of working in a remote corner of Rajasthan. In five years he turned around the derelict primary health centre (PHC) at Gida in Barmer district into a sparkling, efficient facility. The local people could now get dependable primary level care here.

When his tenure ended after five years and he finally left to work at the district hospital, his patients showered him with gifts and wished him a tearful goodbye. It was an emotionally charged parting. And when he goes back now, they greet him warmly.

The PHC had a leaking roof and no systems when he took over. But under his supervision, the health centre got a modern delivery room, a pharmacy and a path lab. Patients’ records were put into a computer. They were assured of medical assistance even at odd hours. There was also much that he did that went beyond the call of duty as a physician. For instance, he got the PHC's roof repaired and tiled. A water harvesting system was installed — crucial in water-deficient Rajasthan. "I wanted to do such a good job that people would remember me for my contribution," he says. He has and they do.

Below is a piece that appeared in Civil Society's September-October 2018 edition. Read on.

When Dr Jogesh Kumar set foot in the Primary Health Centre (PHC) at Gida in Barmer district of Rajasthan, he found himself in calf-deep water in the reception area. The facility was dank and dilapidated and the water remained stagnant for all of five days.

|

|

|

|

It is not uncommon to have a few heavy showers towards the end of the monsoon in this desert region where Gida is located. There have even been floods in Barmer. The PHC’s problems, however, had more to do with long administrative neglect than the rain. No one had tried to manage it properly.

As government-run PHCs went, it undoubtedly ranked among the worst in Rajasthan. Its daunting conditions were enough to drive medical talent away. But it was here that Dr Jogesh (as he likes to be called) had arrived on his first posting as a medical officer of the government on August 28, 2013.

It is a date he can’t forget. All of 25 years old, and brimming with enthusiasm, he had done the 100 km from Barmer town to Gida village alone on his motorcycle. The conditions at the PHC were depressing, but he chose to stay. And, moving into his living quarters behind the PHC, he began the seemingly hopeless task of turning the place around.

Five years later, the results of his efforts are worth seeing. The Gida PHC has been transformed into a shining example of a modern, low-cost public health facility. It has clean wards and beds. The toilets are usable. You won’t find litter.

The sanitised labour room with everything in place

The sanitised labour room with everything in place

The labour room is sanitised and has two delivery tables and two baby warmers and a digital clock shining on the wall to record the exact time of birth. Biomedical waste is systematically collected and disposed of. A laboratory at the PHC conducts 15 tests and provides results almost immediately. Vaccines are preserved in a deep-freeze with the required temperature recorded and maintained.

Patients register at a counter at the entrance and their personal case histories are computerised. There is a counter for dispensing free medicines. Stocks of medicines are warehoused, accounted for and replenished on time.

As the PHC’s reputation has grown, it has begun attracting patients from far away. Last year, it treated 36,000 patients, which is about five times the number it used to get. It has handled 70 deliveries in a month compared to just 10 earlier. Since the catchment it serves has increased, it is now poised to become a Community Health Centre, which means it will have more doctors, with at least one of them a specialist, and more nurses and support staff. An X-ray machine will also arrive.

The improvements haven’t gone unnoticed. The PHC has won recognition from the Rajasthan government for handling the largest number of deliveries in the district and treating the most patients in the state among PHCs. It also tops in distributing free medicines.

Before Dr Jogesh arrived, people would come to the PHC because they had nowhere else nearby they could go to get treatment. Gida has a population of just about 2,500 and they are mostly poor people with small landholdings or employed as labour. For a major health problem they would use their savings and somehow make it to Jodhpur or Barmer. But for a fever or a stomach infection it was the PHC they turned to. They had no alternative despite its poor condition.

“I didn’t anticipate what I would find in Gida, but it was my first posting and in my mind I wanted to do a good job wherever I was posted. I wanted to do such a good job that people would remember me for my contribution,” said Dr Jogesh, when we meet at the PHC.

Three months before we met him at the PHC, he had been transferred to the district hospital at Barmer. Civil Society persuaded him to take a couple of days of leave and come to Gida to be interviewed and photographed. His presence loomed large and neither staff nor patients had forgotten him.

Blood pressure readings from a bangled arm

Blood pressure readings from a bangled arm

Raza Devi, 85, a patient with blood pressure problems, spotted him and said affectionately: “You, what are you doing here? Have you come back?” She was at the PHC for her regular blood pressure check-up and medicines. “He is a very good doctor,” she tells us. Her son, Ghamma Ram, endorses that and says to us: “All the facilities that you see have come because of him. He changed this place completely.”

Indra Singh, 20, also happens to be at the PHC. He had diabetes for many years till it was diagnosed here by Dr Jogesh. He was put on insulin, which he gets from the PHC. “Dr Jogesh showed me how to manage my diabetes. I learnt to take insulin injections,” says Indra, who is short and frail.

“Basically I am from this area — Barmer district. I understand the people and wanted to do something good for them,” says Dr Jogesh. “I wanted them to experience the benefits of having a functioning government health centre.”

“I don’t have words to describe the love and affection I have received from patients. When I was transferred from here to the district hospital, some of the local people gave me farewell gifts of silver utensils, a ring, a chain. It was from their hearts with love and affection. I felt that I had done my job well as a doctor,” recalls Dr Jogesh.

“Money has its own place in our lives. It does matter. But compared to what I could have earned in private practice, the appreciation I received is worth much more to me,” he says.

Government doctors are allowed to see patients privately outside their official duties. Dr Jogesh chose not to because he wanted patients to go to the PHC and have faith in the government system.

“If I had opened a clinic, many patients would have preferred to spend a hundred rupees and come to me directly. Instead I focussed on making the PHC functional so that people could see what the government system could give them. Once people become part of a functioning system, they prefer it,” Dr Jogesh explains.

For the first six months of his tenure, Dr Jogesh petitioned officials in the health department and local district officials to help improve the facilities. He waited several weeks but got no response. He then decided to involve the local community.

He identified several reasonably well-off people who had begun coming to the PHC for treatment and took their mobile numbers. Then, with the help of a social worker, he invited them to a meeting.

“I told them that I wanted to improve the PHC, which would benefit all, but I didn’t have the money. If they could make donations, I would use the money to repair the roof, which would make the PHC more functional,” recalls Dr Jogesh.

“People had seen me working in the PHC and attending on them despite the terrible conditions. They had seen me making an effort. So, when I asked them for their support, they readily came forward,” says Dr Jogesh.

In that first round of donations he collected Rs 6 lakh. He used Rs 4 lakh to repair the roof and tile it and the remaining Rs 2 lakh he put away for other incremental improvements, which began with tiling the walls of the labour room.

Fixing the roof was a big achievement. It took about 25 days and transformed conditions inside the PHC. He hired a local contractor and told him to use the best materials so that it never leaked again.

“When people made the first donations they might have had some doubts about the use to which I would put their money. But once work on the roof was completed, and the contractor being a local man told people I hadn’t spared any effort to spend their money well, people were convinced,” says Dr Jogesh.

Over five years, Dr Jogesh raised Rs 14 lakh from local people. There were the well-off locals who gave as much as Rs 30,000. But there were also those who were poor who wanted to give Rs 50 or Rs 20 as their contribution.

“I didn’t stop them,” says Dr Jogesh, “because I wanted everyone to have a sense of involvement. The well-off people could afford private doctors and did go to them, but they realised the need for a reliable local public facility. They sought nothing in return except occasionally sending a patient and asking me to pay special attention, which I would readily do.”

Transparency was also important and accounts were provided for all the expenditure. The names of the donors and the amounts they gave were also put on standees at the entrance to the PHC, thereby providing identity and a sense of ownership.

Dr Jogesh wanted the PHC to be respected for its professionalism. He put systems in place. He set timings for seeing patients. General consultations could only be done in the morning till noon. Cases which came in the evening would have to be emergencies. Earlier, people used to walk in at any time. He also enforced a charge of Rs 10 and set up a counter at the entrance where patients had to pay and register.

After fixing the roof, Dr Jogesh employed donations to make innumerable other improvements such as painting the PHC, installing an RO system for drinking water, having battery back-up for power failures, rainwater harvesting which provides 15,000 litres of water in reserve, a solar water heater for the maternity room, a garden and a paved area to reduce the sand around the PHC.

A washing machine was bought with a donation so that the linen used at the PHC could be washed there itself. As a result, the beds all have clean white sheets. For a car park, he got Rs 5 lakh from the development fund of the MLA of the area.

A PHC plays an important role in the country’s healthcare system, being the lowest tier and located in the midst of the community. People tend to go to a PHC first because it is near them. If the facilities are good and the doctors are efficient, a PHC can identify diseases in their early stages and help patients find treatment at bigger general hospitals and specialised institutions.

At a PHC it is possible to deal immediately with snakebites and dog bites and small injuries. A fracture can get interim attention till the patient is taken to an orthopaedic in a bigger hospital.

A well-functioning PHC also increases the number of institutional births. By being in close touch with a woman through her pregnancy it makes sure she is in good health and that she gets to the maternity room in time. Likewise for child health. A PHC will be able to know if a child is underweight and malnourished and can counsel the mother.

So, when it comes to improving maternal mortality and infant mortality, a PHC is quite indispensable. The Gida PHC has eight sub-centres and eight auxiliary nurse midwives. A woman is tracked from the time her pregnancy begins. Since the PHC has a well-equipped labour room and a clean and well-attended maternity ward, women come to it for their deliveries. Its success on this score shows in the growing number of deliveries it handles.

Medicines are properly stocked

Medicines are properly stocked

“You will find every kind of disease at a PHC,” says Dr Jogesh. “There will be hypertension, diabetes, tuberculosis, cancer and so on. The problem is that patients get diagnosed, go to some distant facility and don’t come back. I began stocking medicines so that patients would come back for check-ups and to replenish the medicines. It was all available through the government. All we had to do was to maintain stocks, indent on time and follow up with the place from where the supply was to come. When patients were assured that they would get medicines and attention they would come back.”

The PHC’s role as a sentinel can’t be emphasised enough. In a rural area someone with a cough may not realise that it is tuberculosis, but a doctor at a PHC can at least suspect tuberculosis and send the patient to a bigger hospital. Sputum tests are also done at the PHC in Gida.

Dr Jogesh recalls the case of a patient who came to him with a nodule on his neck. He had gone to several big cities for treatment and had been prescribed antibiotics which would have some effect but the nodule would return.

Dr Jogesh sent him to Jodhpur Medical College to be checked for cancer. It turned out that he had cancer of the larynx. From Jodhpur he called Dr Jogesh to ask him what to do because the specialists there were asking him to undergo chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

“Patients develop bonds with their local doctor at the PHC,” explains Dr Jogesh. “I had to reassure him about the treatment and explain to him that if he didn’t take the treatment his problem would get worse. Finally he was successfully treated and is living a normal life. He became one of the regular donors to the PHC whenever money was needed.”

Can every PHC be transformed the way the one at Gida has been? Dr Jogesh is sceptical. He believes that a lot depends on circumstances and individuals. There are problems and the risk of upsetting people in authority by being too pushy.

Patients queue up to see the doctor

Patients queue up to see the doctor

“There is no simple answer. I might not have been able to do the same thing elsewhere — in Bihar for instance. So much depends on one’s family background and personal life. Someone from a big city would have found it very difficult here. It is 70 km from the highway,” says Dr Jogesh.

He feels it is important for the government to allow doctors to work where they are most at ease so that they can be effective. Someone could choose the city, someone else the village. A city-bred doctor may not be successful in a remote village.

Dr Jogesh’s replacements are Dr Satya Narayan and Dr Amit Tak, both enthusiastic young physicians. Dr Tak was sent as an interim measure till Dr Satya Narayan was posted to the PHC but the chances are that he will stay on. They have inherited a working system. As patients pour in, they have their hands full.

Mooli Devi, 25, is nine months pregnant and arrives saying she has labour pains. Dr Tak has her checked and tells her family that these are false pains. She doesn’t need to be admitted just yet.

Paku Ram, 20, has had a fever for several days. He has come from Danpura, 15 km away. A sub-centre of the PHC had given him some tablets for three days but they didn’t help. Dr Tak suspects typhoid and sends him for a blood test to the PHC’s laboratory. In minutes it is confirmed that he has typhoid and now Paku Ram’s correct treatment will begin.

Polu Ram, 60, has come from Kokhsar, which is 50 km away. He has been feeling unwell and doesn’t know why. A test shows he has high blood sugar and is diabetic. He is a new patient. Pallu Devi, 55, is a regular with hypertension, but she hasn’t been taking her medicines and so her blood pressure reading is 164/100.

A laboratory conducts 15 essential tests

A laboratory conducts 15 essential tests

Till noon, the PHC buzzes with activity. Rajaram, the young laboratory attendant, who works on contract, is a busy man doing blood and urine tests. Sunita Jangir is a nurse but her duties include ensuring that vaccines are kept in the cold chain and attending to the reception where she registers patients. Ghanshyam looks after the warehousing of medicines and Rakesh doles them out.

Umesh Anand and photographer Shrey Gupta travelled to Gida in Barmer district of Rajasthan to meet Dr Jogesh Kumar and see the PHC

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!