Begari Lakshmamma

In Humnapur village of Telangana, no farmer buys seeds from seed companies. They don’t need to, because Begari Lakshmamma’s seed bank has 60 to 70 varieties of native seeds. The objective of the seed bank was to reduce dependence on seeds manufactured by companies and to conserve native varieties. Nearly half the village borrows seeds from her. Some from adjoining villages also make the journey to her doorstep to pick up seeds.

Lakshmamma’s seed bank was set up in the early 1990s with the help of the Deccan Development Society (DDS). When the villagers were looking for the custodian of a seed bank, her name was recommended with overwhelming consensus. She is a single mother and a Dalit and respected in the village community.

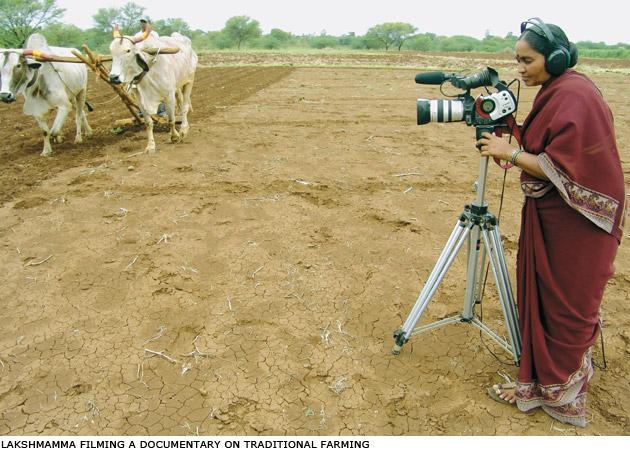

Her seed bank is her first passion. Filmmaking is the second. She combines the two by making documentaries on farming practices. Lakshmamma has worked on more than 300 documentaries and has travelled to film festivals in Canada, Thailand and Germany.

Below is a piece that appeared in Civil Society's September-October 2013 edition. Read on.

Begari Lakshmamma croons softly in a high-pitched voice. Is she singing a Telugu folk song? She laughs. “This song used to be sung by my ancestors,” she says. “Its lyrics tell us when the stars are right for sowing millets. I inherited it.”

Lakshmamma, 45, is a Dalit who lives in Humnapur village in the Medak district of Telengana. A seasoned farmer with five acres, Lakshmamma is a single mother. Her husband abandoned her years ago. He used to work for the Border Security Force.

Inside her neat home, Lakshmamma has a treasure she nurtures with devotion. It is a rare seed-bank of 60 to 70 varieties of native seeds stored in earthen pots.

The origins of her seed-bank date to the early 90s. At that time the Deccan Development Society (DDS), an NGO, had started working in Andhra Pradesh to restore farming and promote millets. Seeds, manufactured by companies, had begun proliferating in the countryside, replacing native varieties. DDS realised how critical it was to set up seed-banks, conserve biodiversity and inform villagers.

“During a meeting in Humnapur we asked villagers to suggest somebody who could be the custodian of a seed-bank. In one voice all the villagers shouted Lakshmamma’s name,” recalls P.V. Satheesh, director, DDS.

So the NGO began to encourage Lakshmamma to start a community seed-bank. Lakshmamma was very successful. Over the years she collected an amazing range of native seeds, including millets, oil-seeds and legumes. You can now see 30 types of millets and legumes and six varieties of green gram. She has pigeon pea in five avatars and jowar (sorghum) in six.

All her seeds are tried and tested. She plants them on her land. About 50 families, or half the village, borrow seeds from her. A few farmers from adjoining villages trudge to Lakshmamma’s home to ask for seeds. And they are never disappointed.

Instead of cold cash, farmers who borrow seeds have to repay with ‘interest’. This means that after harvesting their crops, they have to return double or one and a half times the number of seeds they had borrowed from Lakshmamma’s seed-bank.

Homegrown wisdom: Humnapur, a semi-arid region, receives 800 mm of rain but it faces recurrent bouts of drought. Rainfall is erratic. Sometimes, Humnapur’s entire quota of rain falls in one big burst and doesn’t spread itself out during the monsoon. So the agricultural schedule of farmers goes awry.

The food people eat here consists of local diverse crops. Each dish is a healthy mix of cereals, pulses and oilseeds.

“The daily meal of a traditional Deccan farmer consists of sorghum roti, pigeon pea dal, uncultivated greens seasoned with oil and powdered spices,” explains Satheesh. “The most interesting aspect of this meal is that every single element is grown on their own farm, however small. Crop diversity is directly transferred from their farm to their kitchen.”

The thoranam, for instance, is an indicator of how much people value this diversity. It is a string with earheads of different crops, interspersed with mango leaves, strung across the front door during festivals. Lakshmamma’s neat home has one. Endlagatte Punnam festival falls on a full moon day that precedes the winter harvest. Men and women collect earheads from their fields, days in advance. The earheads, sweets and cooked rice are offered to the village goddess as a gesture of gratitude for blessing them with a good crop.

Every house owner takes great pride in displaying the diversity of crops on his or her field on the thoranam.

Crops of truth: Traditionally people here kept hunger at bay by planting crops in the rabi season that ‘grow with the wind.’ Such plants are called ‘crops of truth’ by villagers (satyam pantalu) and consist of jowar, chick pea, safflower, wheat and flax.

Also included are millet (bajra) varieties like proso millet and little millet. These crops have the added advantage of being resistant to pests and diseases.

Lakshmamma’s seed-bank stocks several ‘truth crops’. She has three varieties of little millet and the rarer Kodo little millet that has now become popular. These millets are close to extinction so Lakshmamma is trying her best to conserve them and make them popular. To maintain a stock of seeds, she keeps 10 per cent of small seeded crops and 25 per cent of big seeded ones.

Lakshmamma’s seed-bank yields a surplus that she can sell and earn an income. From her home and through her self-help group, (SHG), Lakshmamma sells seeds of pigeon pea, green gram, black gram, dolichos lablab, safflower and millets.

Lakshmamma lost her parents some years ago. She and her two children live with her brother Gundappa, his wife Shankramma and their four children. Her daughter Geetha has a B.Com degree and her son Narasimhalu works for a chemist.

Hereditary profession: Traditionally, every village in these parts had a seed-keeper. Farmers fervently believed that taking seeds from a seed-keeper would yield a bountiful harvest for they were considered auspicious. So Lakshmamma isn’t new to the idea of seed conservation. Her grandmother, Sangamma, ran a community seed- bank decades ago.

Seeds stored in earthen pots were placed one on top of the other. Rats and other pests were kept at bay. Lakshmamma follows traditional methods to protect her seeds from pests.

“Green gram is very vulnerable to pest attacks,” she says. While storing she mixes foxtail millet in green gram and black gram to protect the seeds from pests. The foxtail millet fills up all the airy space between the green gram and black gram. So even if weevils find their way in, they will die of suffocation. When the seeds are required, the millet is strained out. Mixing seeds with cow dung ash and neem leaves also protects them from pests.

“During my grandmother’s time, we had many more seeds,” recalls Lakshmamma, “We have lost forever two or three varieties of jowar and wheat.”

Lakshmamma’s parents were very poor so she never had the opportunity of going to school. But she is intelligent, cheerful and has a pleasing personality.

Dalits like her used to be landless. A few had bits of land they didn’t cultivate. Mostly they spent all their time slaving on the fields of landlords leaving them with no time to plough their own fields.

As a result of land reforms by late Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, Dalits here were allotted one or two acres each. These lands are called ‘Indira bhoomi.’ But the Dalits saw their lands as unproductive and didn’t work on them.

Things started changing when DDS began an employment scheme in the summer of 1988 uncannily similar to the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS). They offered 75 per cent of wages to people who were willing to do 100 days of work on their own field.

“In a decade’s time, about 15,000 acres of fallow land was brought under cultivation,” says Satheesh.

By then native seeds had started disappearing. Satheesh blames this loss of biodiversity to chemical farming and the availability of rice through the public distribution system.

At that time DDS relied on Lakshmamma’s excellent communication skills. She reasoned with neighbouring farmers and addressed village meetings explaining why native seeds were so important. DDS employed her at their seed-bank at their headquarters at Pastapur.

Over the years with awareness of native seeds increasing, farmers have started preserving their own seeds. Fewer people approach Lakshmamma for her seeds. But she doesn’t worry about shrinking demand.

“That’s fine,” she smiles. “I will simply sell all my produce and keep only the seeds that I need.” Private companies manufacture hybrid pigeon pea and jowar seeds. Lakshmamma says none of the farmers in her village or the adjoining ones buy from seed companies.

Seeding film: Seed-keeping isn’t Lakshmamma’s sole skill. She is also a proficient film-maker, wielding the camera with as much passion as she nurtures her seeds.

DDS has trained about 12 women in film production. Lakshmamma is among them. None of the women know English or any other link language. Yet, apart from producing short local films, they have undertaken a number of film assignments abroad.

Lakshmamma began filming around 20 years ago. Till date she has contributed to more than 250 to 300 documentaries. As a film-maker she has travelled to Bangladesh, Cambodia, Senegal, Mali, Canada, Thailand, Germany and the UK.

In India, during the annual biodiversity festival, Lakshmamma and her colleagues made a number of films on successful award-winning farmers. They have also taken part in film festivals held in Delhi, Pune, Bangalore and Thrissur.

How does a rural woman who is not literate learn how to handle a camera? The question irks Satheesh. “Why do you think English is necessary to ideate an issue and transfer it to film? Its only when the women travel abroad that they need a translator.” Satheeesh, a visual communications expert, rates Lakshmamma’s skills as a film-maker pretty high. “I would give her seven out of 10,” he says.

Ask Lakshmamma how many documentaries she has made and she replies that she can’t remember. “The first one I did was on anganwadis,” she recalls. “But I wasn’t satisfied with it. I prefer to film seeds and crops since that’s very close to my profession.”

She says seeds are her first priority. The second is filming. Glancing at a calendar she says she will be shooting a film on farming a day later in a nearby village.

It is her seed-bank that is always on her mind. “Now that it is raining it is time to sow seeds like horse gram. Farmers in the village I will be going to have asked me for seeds. I will take them along with my camera,” she says, thoughtfully.

Shree Padre took a flight and a taxi to meet Lakshmamma

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!