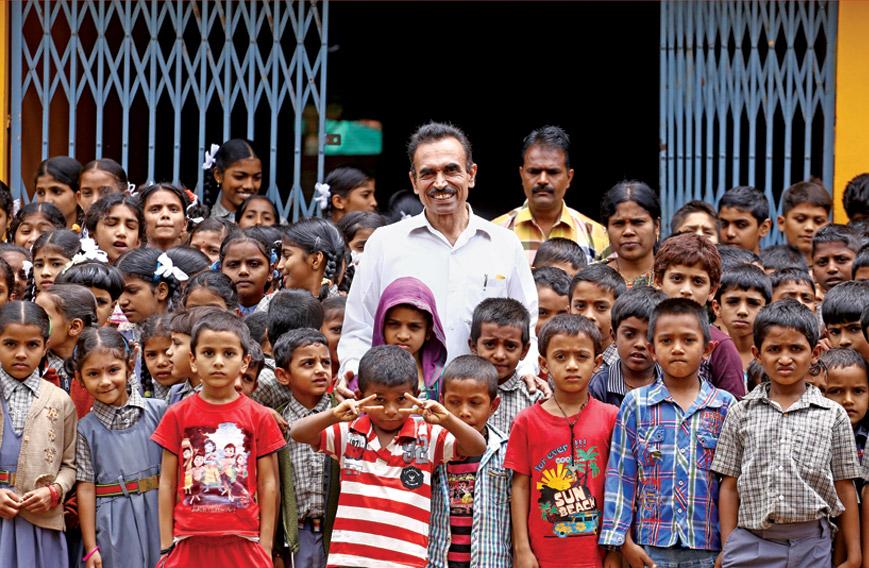

Honnesara Paniyajji Manjappa with students at the Vanashree school at Sagar

Honnesara Paniyajji Manjappa

A child labourer on a coffee plantation is now an assistant engineer in a power corporation in Karnataka, because of ‘Manjappa Mama’, as he is lovingly called by many of his students. Honnesara Paniyajji Manjappa runs three Vanashree schools in Shimoga district of Karnataka. Whatever he earns from selling policies of the Life Insurance Corporation, he puts into his schools. His commitment is rewarded by the love he receives from his students.

The three schools together have about 1,000 children from 14 states. Only 20 percent of students can pay tuition fees. The schools receive enough donations to educate the rest for free. Vanashree is home for most of the students. Risa, from Meghalaya, joined the school when she was eight. Everything she needed, clothes or slippers or books, was provided by the school. Her attachment to the school runs deep. At Vanashree, the slogan is, ‘My school is my home.’

As a young child, Manjappa battled many serious illnesses like polio and jaundice. It cultivated in him a mental strength to withstand life’s vagaries. He passes on the same strength to his students who flourish under his mentorship.

Below is a piece that appeared in Civil Society's September-October 2016 edition. Read on.

Dressed in spotless white Honnesara Paniyajji Manjappa smiles warmly at the children sitting behind a long narrow desk. The classroom is octagonal so that every child faces the teacher. No one can be a backbencher at the three Vanashree schools Manjappa runs in the Shimoga district of Karnataka.

Dressed in spotless white Honnesara Paniyajji Manjappa smiles warmly at the children sitting behind a long narrow desk. The classroom is octagonal so that every child faces the teacher. No one can be a backbencher at the three Vanashree schools Manjappa runs in the Shimoga district of Karnataka.

The faces of the children reveal that they are from all over India. Mostly they are destitute children, rescued child labourers, juvenile delinquents, dropouts and children whom other schools turned away.

Vanashree throws its doors open to them. So far since 1990 about 3,000 students have gone through the Vanashree schools. Of them100 have got admitted into medical, engineering and professional colleges. Some are working abroad. Whenever they come to India, they visit the school that transformed their lives.

Currently, the three schools together have about 1,000 children enrolled. Of them 20 percent are from well-to-do homes and pay fees, which add up to Rs 15-20 lakh annually. Manjappa puts the commission he earns from selling policies of the Life Insurance Corporation (LIC) into meeting the costs of the schools. For the rest, he depends on donations.

All the children, regardless of which state they come from, learn Kannada and speak it fluently. “It isn’t difficult to teach. The children learn in a year. Knowing the local language has many advantages. They can communicate with everyone. Otherwise, they would miss out a lot,” says Manjappa.

Manju Naik is now an assistant engineer in Ambikanagar’s Karnataka Power Corporation in the Uttara Kannada district of Karnataka. He has a home, a job, and a car. In 2002 Naik was a child labourer slaving at a coffee plantation in Chikmagalur. One day, Naik and 30 other children were dramatically rescued by Manjappa and brought to Vanashree.

Some of the boys ran away saying they didn’t like the food. But Naik, a Lambani tribal boy from Bellary district, stayed on. He studied assiduously and eventually graduated from Malnad College of Engineering in Hassan, topping his class.

“I have a decent government job, a place to stay and a car. My mates who ran away are back to where I was as a child — working as labourers. I am what I am because of Manjappa Mama,” says Naik, with gratitude in his voice.

Manjappa’s schools have students from 14 states — Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Uttaranchal, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Delhi, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Goa, Assam, Manipur, Nagaland, Punjab and from Karnataka’s 30 districts.

Around 30 percent of students are categorised as ‘educationally backward.’ Yet in the past 16 years, not a single child has failed the Senior Secondary School Leaving Certificate (SSLC) or Class 10 exam.

Fourteen-year-old Bianglin is an orphan from Meghalaya. When she joined Vanashree she was shy, insecure and fearful. She could only speak Khasi, her mother tongue.

Bianglin is now fluent in Hindi, Kannada, and English. She has also learnt music, Bharatanatyam, and yoga. A confident girl, now in Class 9, Bianlin is invariably chosen to be master of ceremonies during school programmes.

“My ambition is to become a doctor,” she says. “A person from Sirsi has promised to sponsor me if I do well in my studies,” she says, her eyes reflecting hope.

THE JOURNEY

Manjappa is now 61. He is the eldest of nine children in his family. His parents, Lakshminarayanappa and Tharavathi, were farmers and eked out a living. As a child, Manjappa faced a series of health problems. At the age of three, he got polio. One leg became shorter by four inches. His mother would massage his legs for hours trying to correct this deformity. When he was five, a bout of jaundice almost killed him. A local vaid’s medicine miraculously saved him. In fact, by the time Manjappa was an adolescent he had already battled several illnesses.

Coping with illnesses had two fallouts. At 15 he learnt yoga that made him stronger psychologically and physically. He also acquired a strange confidence in himself to make the impossible possible.

Manjappa joined the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and became an activist. He says it gave him the opportunity to meet people, both rich and poor, and understand issues in education and the environment. In 1979, he organised a summer camp for students, a new concept in those days. “That camp opened my eyes. I had to answer hundreds of questions asked by students. Compared to this what I had studied in college was nothing. I learnt a lesson — education is not about blurting out all that you know. You should be able to reply to questions asked by curious students,” he says.

Manjappa started his first school in temporary thatched huts in Bachchodi to provide education to Kudubi tribals. Alongside, he began two more schools one at Varadalli Road in Sagar and the other at Ulavi.

The main school at Sagar and the school at Bachchodi are residential. The school at Sagar has 600 students and classes from lower kindergarten to Class 10. The school at Bachchodi has 200 students and classes from upper primary to Class 7. A third school at Ulavi, also upto Class 7, has 200 students, but isn’t residential.

At Vanashree the slogan is, ‘My school is my home.’ The schools balance education with emotional stability. Parents are given five assurances when they admit their children. Two are worth recounting: students who have studied here for five years will face life confidently and never contemplate committing suicide. They will learn to tackle water shortages.

“Our students are of strong character. They can tackle criticism, harshness, face interviews and emerge successfully. Appreciation of culture is an intrinsic part of schooling,” says Manjappa, who is called Vanashree Manjappa in Sagar.

OCTAGONAL CLASSROOMS

Vanashree schools have implemented many innovative ideas. The school in Sagar has 22 octagonal classrooms in little thatched huts. It has 24 teachers. The maximum number of students in a class is 30. The school also has 21 non-teaching staff.

Manjappa talks to students. Classrooms are octagonal.

Children are encouraged to ask as many questions as possible. A lot of learning takes place through seminars — which means that students teach other students. Murali, a Class 4 student, is the teacher in class today. “Plants are very important in our lives. With the help of chlorophyll, they prepare food,” he explains. He has a blackboard but behind the students, there is a whiteboard, where they can write answers or do an exercise assigned by their teacher. “This saves us time. We can evaluate the child’s assignment much faster than answers written in a notebook,” says a teacher.

“Our school is different from other schools. Teaching in one class isn’t heard in the other classes. The surrounding green creates a learning atmosphere,” says Krithi, who studies in Class 10.

Bindu, also in Class 10, says what she likes most is that students teach students. “Because of this, we understand things better.” Emhiba, in the same class, says, “All are equal here. No one is labeled a dull student or a clever student. We discuss our lessons with each other.”

The children are enrolled regardless of their marks. “We start the process of bringing them up to standard,” explains Manjappa. A student who is behind the class when admitted is sent to a special class from June to August to catch up.

The school organises discussions with experts in different fields as well as with its old students. Vanashree teaches its students farming. There is a vegetable patch where children plant various crops. The school also has a unit that teaches the children tailoring. The older children learn to cook.

A group of girls after a discussion with Kalavati Mataji — teachers are addressed as Guruji or Mataji — decided to make pulao for us for dinner. It was well made.

Since most of the children are poor, Vanashree meets all their needs including clothing. After Class 10, children who enroll in local colleges can stay on. Currently, 10 such students are living in the school’s hostel.

CHILDREN FROM MEGHALAYA

Thirty students from Meghalaya are enrolled here. The Meghalaya connection began 15 years ago when a well-wisher brought a poor boy, Sanmi Biam, to the school. His father had passed away and Biam didn’t want to go to school. But Vanashree admitted him and he blossomed. Noting his progress back home, other parents began approaching Vanashree to enroll their children too.

“The social condition of Meghalaya is pathetic. It is a matriarchal society but the flip side is that in many families the men don’t shoulder responsibility. Teenagers acquire bad habits like smoking. Girls are married off very young and become teenage mothers,” says Manjappa.

Risa is from Meghalaya. “I don’t feel this is a school or a hostel. This is our home. Starting from clothes and slippers, everything is provided by the school. Whenever I need something I ask like I would ask my mother. The school has taught me how to live and tackle difficult situations. When I joined the school in Class 3, I didn’t know anything,” she says.

Risa’s dream is to become a doctor so she is studying science. “Even after finishing school, I’ll keep coming here and helping. This is not a second home but my first home,” she says.

Students can approach Manjappa any time. “They don’t need any permission — no appointment slip. They don’t even knock on the door. Even if I am talking to someone influential they can walk in,” says Manjappa. It is parental care that makes Vanashree a home.

The walls of the school are covered with diagrams and information that students can use. The school also offers courses in yoga, meditation, music and art.

Bhavya, a physically challenged girl in Class 10 is from Chattisara, a nearby village. None of the schools she went to earlier could provide her an ambience conducive to her needs. Her parents were worried. Vanashree admitted her. Since Bhavya couldn’t walk, her parents would physically carry her to the school. Darshan, who is studying in Class 8, had dropped out of half a dozen schools earlier.

Why do students face learning difficulties and find it hard to adjust to school? “They just lack self-confidence,” says Manjappa. “They lose self-esteem when teachers abuse them, call them dull and beat them. We taught Bhavya yoga and pranayama and built her self-confidence. Within two months she started walking and is happy in school.”

Vanashree's hostel. Children who get admitted to college can continue to stay here

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!