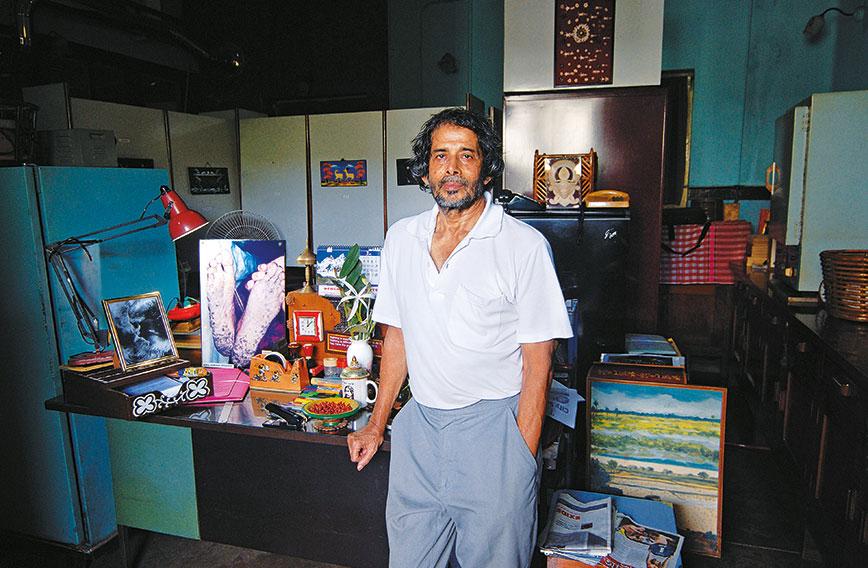

Dipankar Chakraborti

In the 1980s, long before India had woken up to the problems of automobile emissions, Dr Dipankar Chakraborti, then a young professor of chemistry, was out on the streets of Calcutta collecting air samples. He would test the samples during his teaching stints in Europe and bring the worrying results back.

He warned of cancer and asthma and the generally debilitating effects of air pollution. Back then no one was listening, but many of his concerns came true for Calcutta.

Dr Chakraborti was an insightful and public-spirited professor. He forayed far out of the classroom and into the real world, fearlessly shaking it up.

He sounded alarm bells over the presence of arsenic in groundwater in West Bengal and Bangladesh. Later he also found eastern Uttar Pradesh to be affected. He was pilloried by politicians who didn't want a problem they didn't know how to fix.

When he died in 2018, he had withdrawn from the School of Environmental Sciences that he had turned into a powerhouse of inquiry and useful research. Most tragically, he had begun losing his memory, but he was fit enough to dance in the rain on his terrace months before his end came suddenly.

Civil Society has tracked Dr Chakraborti's work over the years. Below is a piece that appeared in the edition of September-October 2012. Read on.

The arsenic research unit of the School of Environmental Studies at Kolkata’s Jadavpur University is housed in a nondescript sarkari type building with grey walls and dusty furniture. But the world changes as soon as you climb the stairs and face the entrance.

You are asked to take off your shoes, the floor is spotlessly clean and there is a profusion of potted plants all around. The fine cracks that have appeared on the antique floor have been painted over in bright coloured strips creating an appealing pattern.

Obviously, unusual spirits reside in the laboratory and the one that drives it can be seen in one corner of a large room filled with scientific equipment, and of course potted plants, seated cross-legged on a backless stool before a sleek Dell laptop and framed pictures of Rabindranath Tagore.

Dipankar Chakraborti, director of research at the school, does not look his 69 years. The only habit forming stuff he imbibes is a cup of tea and coffee a day and confesses that has a weakness for coffee which smells good. He is mostly a vegetarian and has a bit of fish only when his daughter insists he taste some prepared by her. He eschews allopathic medicine.

He is usually up at four in the morning and spends two hours doing yoga while listening to Rabindrasangeet on FM radio. Then begins his workday which leaves him no more than two to five hours of sleep and precious little time for his family.

He regrets that for much of his daughter’s childhood, he had only seen her asleep. He would be in after she had gone to sleep and up and out before she was awake. His wife first snorted when he told her that he remembered her at least 100 times a day, and wasn’t amused when he explained that he had made her name the password for his e-mail ID.

For over 20 years now Chakraborti has been a kind of single issue fanatic – mapping the presence of arsenic in the groundwater of the Gangetic delta, recording the havoc that it has wrought on unsuspecting people and trying to sensitise multiple governments to the dangers of arsenic poisoning and the need to mitigate and prevent it.

After spending around a decade overseas in various research capacities he decided to return to India in 1988 to devote himself entirely to the study of arsenic. During the first few years, till 1994, he faced endless insults as he banged on closed doors. Then in 1995 he organised a conference of scientists from all over the world who endorsed his method and findings. In a sense, the cat was out of the bag.

Chakraborti turned down a request for an interview to do a profile of him as, he explained over the phone, he did not want to project himself personally. His work would speak for itself. In keeping with this he had recently declined a personal recognition from a local chamber of commerce and had agreed to go and receive the award only after it was given to his school. So this piece relies on all the media coverage that his work has attracted – and there has been a lot of it – and what is part of folklore.

One of the stories is either apocryphal or wholly true. A man came to see him in 1996 and told him that he was ending his one year assignment of trailing him, having been put on the job by the state agencies to find out what exactly he was up to. The Left rulers of West Bengal were paranoid that he was a foreign agent set up to create panic and spread social unrest. The man said the final report would say that Chakraborti was a “mad man, a workaholic and arsenic runs in his blood.”

Not satisfied with working in West Bengal, he took his work to Bangladesh in the early nineties and there initially met with the same disbelief and hostility. People from there attended his 1995 conference, only to say there was no arsenic poisoning in the country. Then in 1996 he was offered a small window of opportunity to do field work in Bangladesh. At the end of his work when he presented his findings to the media in Dhaka it made national headlines.

He has passed on to Jadavpur University all the money that he has earned through consultancy in the last 24 years on the understanding that the interest income from it will be used to help arsenic affected people and pay for the upkeep of the greenery that is present in and around his laboratory. The corpus now totals `1.08 crore.

He retired in 2008 but was allowed to carry on till 2013, the cost being met from the income of a grant of `50 lakhs which was also passed on to the university. It is clear that Chakraborti will never retire in mind and spirit, irrespective of his official status, driven as he is by his all-consuming passion for his work.

Comments

-

Hari Ramudamu - Oct. 30, 2021, 9:27 p.m.

Dr. Dipankar Chakrabarti is indeed, a price jewel in Environmental Science for his significant contribution in the field of arsenic studies and various facets of environmental analysis. He is one of the highly respected academician and might get to read the certain side of his works that one could hardly get to learn imparting the rare knowledge from his inferential nature towards the changing environment.