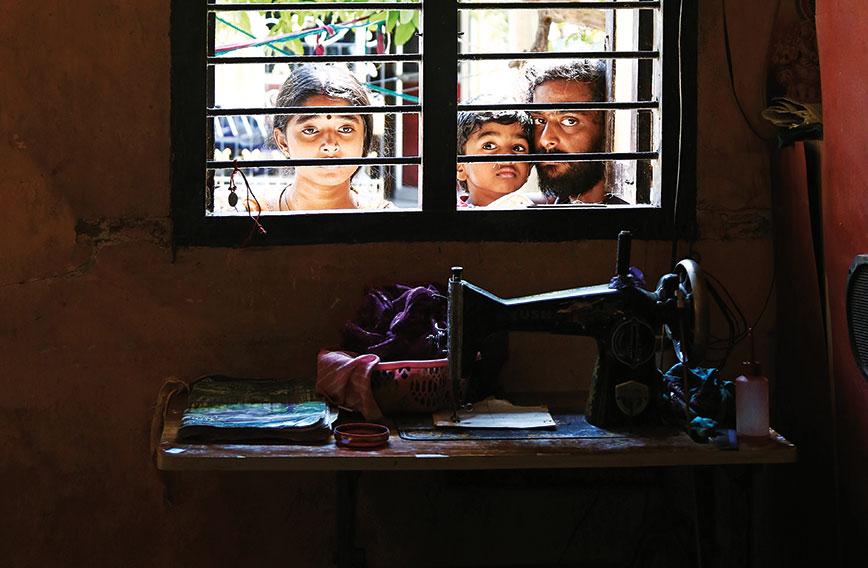

A still from To Let, a film about a desperate search for an affordable home in Chennai

'To Let’ is about being homeless in Chennai

Saibal Chatterjee, Chennai

Despite having shot nine films over 10 years and a bit, including the 2007 Indian Panorama entry Kallori, Chennai-based cinematographer Chezhiyan Ra was barely known outside the state of Tamil Nadu. Between November and February, however, life has taken a new turn for him. His directorial debut, To Let, fetched him two major festival prizes in the span of four months.

Set in 2007, when the IT boom in Chennai sent house rents through the roof and put the less fortunate at a severe disadvantage, To Let is a hyper-realist observational drama about a film industry struggler looking for a home for himself and his young family in the city. The film crafts no pretty frames nor sugarcoats the plight of a protagonist compelled to resort to desperate measures to tide over his predicament.

Much of To Let has been inspired by Chezhiyan’s own bitter experiences. “The film,” he says, “is semi-autobiographical. I went through a similar struggle not all that long ago. I know exactly how it feels when most decent housing units in the city are suddenly beyond your financial reach simply because you do not belong to one particular sector of the economy.”

Written, directed and lensed by Chezhiyan himself, the independent film won the top prize in the Indian language cinema competition section at the Kolkata International Film Festival in November. In February, it garnered another important award — the FIPRESCI (the International Federation of Film Critics) Prize at the 10th Bengaluru International Film Festival. The two trophies have established the first-time director as a talent to watch.

The prizes were richly deserved because To Let is a brutally honest, intensely human portrait of a family thrown into turmoil for no fault of its own. The film explores the ramifications of greed on ordinary people who lack the means to fight back. The protagonist of To Let, Ilango, an aspiring screenwriter and assistant director, lives in a cramped, poorly maintained house with his wife and son.

The paint on the walls is peeling, the toilet drain is always clogged, the kitchen is a musty cubby-hole and the air that flows in and out of this dispiriting abode smells of soul-killing staleness. That, however, does not stop the landlady from wanting to get rid of her old tenant so that she can demand a higher rent from a more financially stable house-seeker.

The challenges that Chezhiyan faced in completing the film were as daunting as Ilango’s struggle. Eventually the filmmaker had to dig into his personal savings to wrap up the film, which explains why his wife, Prema Chezhiyan, a music teacher and book publisher, is credited as the producer of To Let.

The challenges that Chezhiyan faced in completing the film were as daunting as Ilango’s struggle. Eventually the filmmaker had to dig into his personal savings to wrap up the film, which explains why his wife, Prema Chezhiyan, a music teacher and book publisher, is credited as the producer of To Let.

Ilango rides around the city on his rickety moped in search of an alternative dwelling after the landlady gives him a month’s time to vacate her house. The turn of events sparks tension between him and his wife, Amudha, who is fond of growing flowering plants and only desires to be left alone. Their son, Siddharth, a boy who loves painting, plasters the walls of their one-bedroom house with his scribbles and paintings, blissfully oblivious of the crisis that has hit the family. The schoolboy is a bit like the carefree sparrow who flies into the house whenever it likes.

Ilango’s undoing is the fact that he belongs to the movie industry and the house owners he approaches will have nothing to do with a man who does not have a steady income and is seen as a potential troublemaker. So he seeks to pass himself off as an IT professional — with disastrous results.

“The situation was really desperate. It is highly ironical that in a state that has been ruled by film personalities for six decades, industry people have such a tough time getting homes on rent,” says Chezhiyan, echoing a line of dialogue delivered by a character in his film.

“As a witness to what was unfolding around me, I decided to record the situation without any compromises,” he says. To Let was guerrilla filmmaking at its most basic, shot on the sly with real people and at real locations without taking official permission. “I had to opt for obscure suburbs of Chennai because in the more crowded, happening parts of the city it would have been near impossible to film without hindrance.”

The fact that the film has no known faces in the cast helped. The lead actor, Santosh Sreeram, was Chezhiyan’s camera assistant in five films. “He would stand before the camera when we needed to test the light,” recalls the director. “I decided to cast him in To Let because he was just right for the part.”

The sound and visual design of To Let is one of the film’s most exceptional aspects. The manner in which Chezhiyan uses the limited spaces available to him suggests skill and enterprise of very high calibre. “Inside the house, we did not repeat a single angle,” says the cinematographer-director.

Unlike the general run of Tamil films, To Let dispenses with a recorded background score, settling instead for a soundtrack made up entirely of songs emanating from transistors and television sets. “Chennai is a riot of sounds. I wanted to capture the urban cacophony so as to convey the spirit of the city. There was a time when no middle-class Chennai home could do without a radio playing the whole day. Today, it is television. But the sounds are constant,” says Chezhiyan.

The minimalistic approach to filmmaking evident in To Let is Chezhiyan’s way of attempting a clean break from the dominant traditions of Tamil cinema. He is keenly aware of the exciting directions in which world cinema has been moving: Chezhiyan is the author of a series of books titled Ulaga Cinema (World Cinema), in which he examines the dynamics and impulses of the world’s greatest masters.

“Despite being around for over a century, the Tamil film industry has not seen a genuine alternative cinema movement,” says Chezhiyan. “But, given how things are panning out of late, I am hopeful that in the next two to three years a bunch of Tamil filmmakers will put our cinema on the global map. And that wouldn’t be a day too soon.”

Personally, Chezhiyan has set himself two goals: finding a distributor for To Let and convincing a producer to back his next script, which is ready for filming. “There is renewed interest in To Let after the awards that it has bagged, but there is no clarity on how and when the film will be released for public consumption,” says the director.

For filmmakers like Chezhiyan, it obviously isn’t easy finding takers in the commercial space. But as more filmmakers like him, notably Vetri Maaran (whose no-holds-barred Visaranai won a prize in Venice in 2015), Hari Viswanath (whose Radiopetti was a Busan winner the same year) and M. Manikandan (whose Kakkaa Muttai premiered in Toronto), add depth to the Tamil cinema landscape, the industry ecosystem could change for the better. At least that is the hope Chezhiyan nurtures.