Goutam Ghosh’s film links present with Partition

Saibal Chatterjee, New Delhi

The profoundly moving story that unfolds in veteran Bengali director Goutam Ghose’s latest film Shankhachil is set in the present, but the disruption unleashed by the Radcliffe Line drawn in 1947 looms large over the narrative.

The film’s protagonist, played with consummate skill and empathy by Bengali cinema superstar Prosenjit Chatterjee, is a middle-aged schoolteacher in a small, idyllic hamlet on the banks of a river that separates West Bengal and Bangladesh.

With the wounds of Partition still festering in his heart and mind, this victim of history labours to impress upon his young Bangladeshi pupils the primacy of linguistic and cultural affiliations.

Language has no religion, he asserts, even as he is constantly haunted by questions of identity in violently fractious times. No wonder Shankhachil (the title alludes to a kite breed), which was theatrically released on both sides of the border on Bengali New Year’s Day, is a film that evokes “the memory of Ritwik Ghatak”.

Says Ghose: “Ritwik Ghatak captured the pathos of Partition through a slew of characters in films like Subarnarekha, Megha Dhaka Tara and Komal Gandhar. Shankhachil seeks to explore that legacy in a contemporary context.”

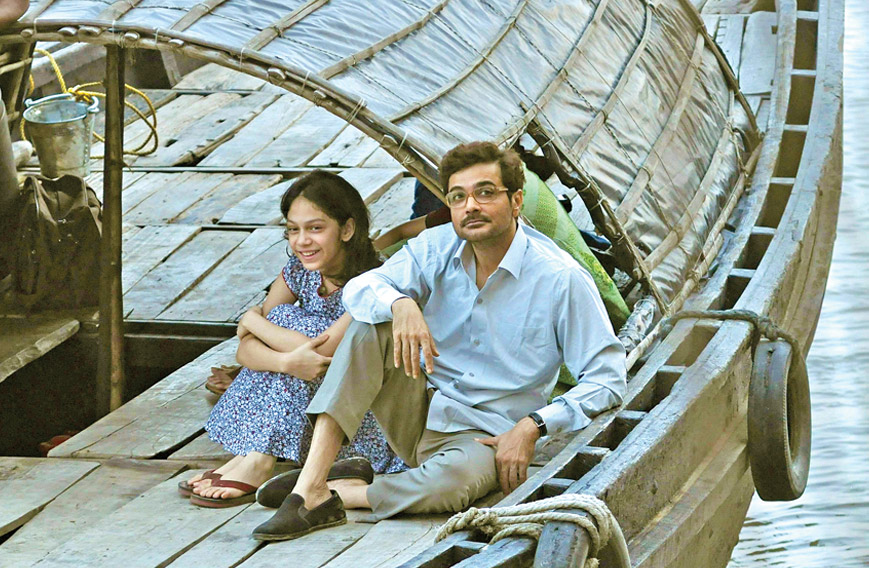

A still from Shankhachil

A still from Shankhachil

Shankhachil has bagged this year’s National Award for the best Bengali film alongside a crop of prize-winners predominantly from glitzy, glamour-laden commercial Hindi cinema.

Shankhachil is Ghosh’s third Indo-Bangladeshi co-production after Padma Nadir Majhi (1992) and Moner Manush (2010). The latter film, too, had Prosenjit in the lead role of Lalan Fakir, a Baul poet and mystic of 19th century Bengal who took on the religious orthodoxy of his time.

The film has a mixed cast, with Kolkata’s Deepankar Dey, Arindam Sil and Ushoshie Chakraborty and Dhaka’s Kusum Sikder, Mamanur Rashid and child actress Shajbati in important roles.

While Bangladesh’s Habibur Rahman Khan has backed all the three Indo-Bangla films that Ghose has directed, Prosenjit is one of the co-producers of Shankhachil, which, in crucial ways, takes the spirit of Moner Manush forward with its celebration of the cultural markers — language, poetry, music — that unite the two nations.

The director is, however, quick to point out that 68 years isn’t a long time in historical terms and, therefore, “the memories of the division of Bengal haven’t gone away and neither are they likely to do so anytime soon”.

That reality plays out in the life of Muntasir Chowdhury Badal, father of a 12-year-old girl with a congenital heart condition. He bears the cross of the cataclysmic event that split the subcontinent forever, while fighting in a quiet and dignified way to clear “the dust of history” that clouds people’s minds.

In one telling scene, he pulls out an old grimy, roach-infested metal trunk from a loft and finds a handwritten inland letter that brings memories of the dark days of the Partition rushing back.

Badal’s worldview has obviously been shaped by the way his grandfather and father had to flee their home on the Indian side of undivided Bengal. He is scarred but not overly bitter.

“Badal is an embodiment of not one but many Bengalis,” says Prosenjit. “He holds in himself a wide range of emotions — fear, doubt, anger. For me, it was a bit like playing several characters in one go.”

Shankhachil is indeed a multi-layered film that alludes to the rising tide of religious fanaticism gripping the world today as well as to the crises related to distress migration across the Indo-Bangladesh border while depicting the emotional trauma of a family struggling to ensure that their pre-teen daughter gets the medical treatment that can save her life.

“Although Shankhachil tells the story of one family, it is a universally topical film given the times we live in,” says Ghose.

Badal and his wife Laila (Kusum Sikder) are compelled to undertake an illegal trip across the border, first to Taki and then to Kolkata, for their daughter’s treatment.

For the girl’s sake, Badal and Laila, much to their discomfiture, have to assume a Hindu identity and acquire fake voter ID cards.

The river that separates the two sovereign nations is also, ironically, the channel that links them inextricably to each other.

Boat trips up and down the river — a recurring visual motif in Shankhachil — reflect the porousness of the 4096-km border between India and Bangladesh, which has more than 100 river crossing points.

Rivers have of course played a key role in many of Ghose’s films – notably Paar, Antarjali Jatra, Padma Nadir Majhi and Moner Manush. In Shankhachil, the river is a constant presence and an emblem as much of eternity as adversity.

Ghose also underscores the emotional impact of the Partition through the metaphor of the shankhachil. The rare bird that has a permanent place in Bengali verse and music thanks to an elegiac, nostalgia-drenched poem by Jibanananda Das — ‘Aabaar ashobi phire Dhansiritir tirey’ (I will return to the banks of this river) — and a timeless song by the iconic people’s music exponent Hemanga Biswas.

“The shankhachil is free and can fly anywhere without hindrance,” says Ghose. “Boundaries are only for humans, not animals and birds. A tiger census on the two sides of the Sunderbans is never fully successful because the big cats move back and forth between India and Bangladesh at will.”

The other principal allegory that Ghose employs in Shankhachil is represented by the story of the little girl, Rupsha, played by Bangladeshi debutante Shajbati. She symbolises the purity and innocence of childhood. “Borders mean little to her,” says Ghose, “but she cannot surmount the barriers erected by history.”

Rupsha (which is also the name of a river in southwestern Bangladesh) is one with nature and loves all living creatures. She releases fish bought by her father into the river, abhors eating the meat that her mother cooks and is thrilled to bits when a dead tree near her home sprouts leaves.

Like the girl, the drying tree that shows renewed signs of life denotes that hope is not all lost. Says Ghose: “Bengal and Bangladesh have been trying to reconnect with each other for years using their common cultural and linguistic heritage but politics does often get in the way of that effort.”

Rupsha strikes up a rapport with a Border Security Force jawan from Rajasthan (played by Mumbai actor Nakul Vaid), who, like Tagore’s Kabuliwallah, sees a reflection of his own daughter in the Bangladeshi girl whose language he can barely understand.

The director uses the word “brutal” to describe the Partition. “It is inaccurate to call this a Partition of India; it was only a Partition of Punjab and Bengal and both the states continue to pay the price for the line that was brutally drawn through them,” he says.

Shankhachil has an eclectic musical track, with the songs and poems of Rabindranath Tagore, Kazi Nazrul Islam, Sunil Gangopadhyay, Annada Shankar Ray, Rajanikanta Sen and Mukunda Das providing a philosophical underpinning to the film.

Ghose also uses a number that Tagore composed in 1905 when he was requested to come up with a song about that year’s Partition of Bengal. He had sung 'Aamaai bolona gaahite gaan' (Do not ask me to sing) in response.

The mournful mood that hangs over Shankhachil pretty much mirrors much of what Tagore would have felt 110 years ago. The scar persists.