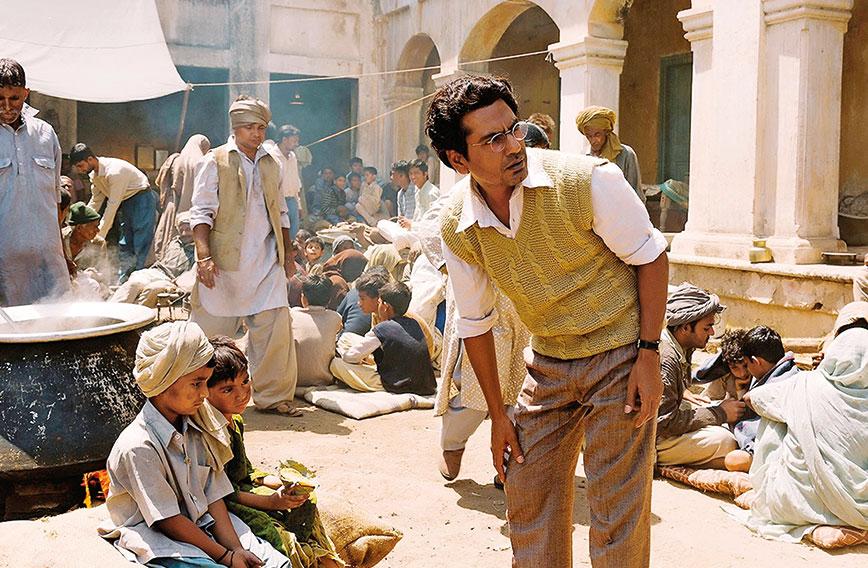

A still from Manto

Manto: Nandita Das’ film on the last years

Saibal Chatterjee, New Delhi

The narrative canvas of Manto, actress Nandita Das’ second film as a director, is separated by over half a century from that of her first, Firaaq (2008). But the two cinematic essays are bound together in spirit and substance. Both deal with the repercussions of sectarian violence on ordinary and not so ordinary people.

Based in the writer-director’s own words, “on a thousand true stories”, Firaaq probed the aftermath of the 2002 Gujarat riots as manifested in the lives of common men and women who bore the brunt of the frenzy that took a toll of more than a thousand lives.

Manto, set in the late 1940s, deals with a situation not dissimilar to what India is passing through today and what it did in 2002. Das’ new film presents an account of the last few years of the life of the iconic Urdu writer Saadat Hasan Manto, who was one of the most uncompromising chroniclers of the Partition riots that rocked the subcontinent during and following India’s Independence.

Manto was himself a victim of the rising tide of communal hate in 1947. Bombay Talkies, where the Urdu writer worked, was a target for mobs shouting “Hindi, Hindu, Hindustan, Muslims go to Pakistan” because it was seen as a studio “with too many Muslims”. He was forced to leave Mumbai with a heavy heart. He never forgot his debt to the city.

Firaaq, made up of a quartet of stories, had Nawazuddin Siddiqui in the guise of a Muslim man whose home is burnt down by rioters. In Manto, he gets into the skin of the eponymous man of letters, bringing him alive with remarkable conviction and power. Says Das: “I always had Nawazuddin in mind for the role of Manto.”

The actor, as always, proves equal to the task. Says Siddiqui: “At the very outset, Nandita and I had decided to concentrate on making everything truthful, not just the physical dimensions of the man, the dialogue delivery or the internalisation of the defining characteristics. I had to be honest not just as an actor, but also as a human being in order to understand Manto’s world and convey it to the audience in all its dimensions.”

The actor, as always, proves equal to the task. Says Siddiqui: “At the very outset, Nandita and I had decided to concentrate on making everything truthful, not just the physical dimensions of the man, the dialogue delivery or the internalisation of the defining characteristics. I had to be honest not just as an actor, but also as a human being in order to understand Manto’s world and convey it to the audience in all its dimensions.”

The process was tough but highly fascinating, says Siddiqui. “It was wonderful delving into the mind of an extraordinarily sensitive man driven to the brink of insanity,” he adds. The inspiration for the actor’s astounding performance would have stemmed in part from the character-defining lines in the screenplay. In one scene, Manto asserts that we have to speak the truth… “When religion leaps from the heart to the head, we have to wear caps,” he says to his worried wife when she wonders why he will not conceal his religious identity in public.

Siddiqui has the support of an impressive ensemble cast, including Rasika Dugal as the embattled writer’s supportive wife Safia and Tahir Raj Bhasin as the flamboyant 1940s Mumbai movie star Shyam Chadda, one of Manto’s closest friends in the film industry.

Besides, the film has, among many others, Ila Arun as Jaddan Bai, Rajshri Deshpande as Ismat Chughtai, Shashank Arora as Shaad Amritsari, Feryna Wazhier as Nargis and television actor Bhanu Uday as Ashok Kumar. Manto also sees Mumbai lyricist-screenwriter Javed Akhtar make his acting debut. He plays Abid Ali Abid, a college principal who stoutly defended Manto in an obscenity case filed against him for the chilling Thanda Gosht.

“I felt it would be a good idea to have a poet of our times speak up for a writer who was under attack from orthodox quarters many decades ago,” says Das, explaining why she cast Akhtar in the crucial cameo.

“In the first draft of the script, the film had a span of 10 years, from 1942 to 1952,” reveals Das. “But I gradually whittled it down to four years from 1946 to 1950, a defining period for both Manto and the subcontinent.”

Manto’s voice — recorded in daring, unsettlingly candid, prophetic stories of religious fanaticism and human barbarity — still echoes in our midst because this part of the world seems condemned to not learning its lessons. “The film is set in the past, but it is just as much about what is happening (in the subcontinent) today,” says Das.

Manto, an Indo-French co-production, premiered at the 71st Cannes Film Festival in May. The topicality of its theme — a writer’s fight for freedom of expression in the face of rampant intolerance and religious and cultural bigotry — wasn’t lost on anybody.

Rasika Dugal plays Safia, Manto’s wife

Rasika Dugal plays Safia, Manto’s wife

Yes, Manto is a period biopic with unmistakable contemporary resonance. It tells the quietly devastating tale of a rebellious writer who stretched himself to snapping point in trying to make sense of a subcontinent caught in a spiral of communal violence at a crucial and tragic point in its history. What enhances the film’s power is its eschewal of the melodramatic conventions of Hindi cinema.

For the Mumbai-based actress-turned-director, the mayhem sparked by the Partition isn’t obviously a distant nightmare. Perturbed by what is going on in India in the wake of a fresh burst of majoritarian assertion, she uses her new film to reflect upon the madness that grips communities when religion becomes more important than humanity.

It was but natural that in this enterprise Das would gravitate towards Manto, a writer, who, in his sustained fight against prejudice, found himself in direct conflict with the moral police and the law on both sides of the newly drawn border. Das, too, has faced troll attacks on social media and elsewhere for not holding back on her outspoken views.

“I used Manto’s writings extensively in developing the film but also used some fictional elements,” she said. “I do films as a means to an end. I realise that it is better to get your point across through the means of a film rather than engage with trolls on social media and in the real world.”

Das’ cinematic take on Manto presents a vivid recreation of a turbulent era. But more importantly, it captures the spirit of a man who refused to accept the fact of being uprooted from his beloved Mumbai. He made no bones about his disgust at the madness that had gripped the subcontinent. About his scalding fiction, Manto had famously said: “If you cannot bear these stories then the society is unbearable. Who am I to remove the clothes of this society, which itself is naked. I don’t even try to cover it, because it is not my job, that’s the job of dressmakers.”

Das’ film brings out the turmoil within Manto and the conflict in the world around him with equal force. “My films,” says Das, “are rooted in a milieu but I do not seek to explain everything. That is how I approached Firaaq, too. If you are true to the emotions that you are dealing with, a film connects instantly with the audience.”

The film delves into several facets of Manto – his relationship with his wife, his friendship and disillusionment with Shyam, his deep connection with Mumbai (where his parents and first-born were buried), his repeated run-ins with the law on account of his acidic pen, his battle with alcoholism and financial troubles – while using five of his most powerful stories, including Dus Ka Note, Thanda Gosht, Khol Do and Toba Tek Singh, to establish the linkages between what he lived and what he wrote.

Manto, Das believes, articulates fierce courage and honesty in the face of heavy odds. “People across the world are fearful of all the unsettling developments around them. That is why Manto’s writings are as relevant today as they were back in his time,” says Das.