PSBT story: 630 films, 230 awards, 400 filmmakers

Saibal Chatterjee, New Delhi

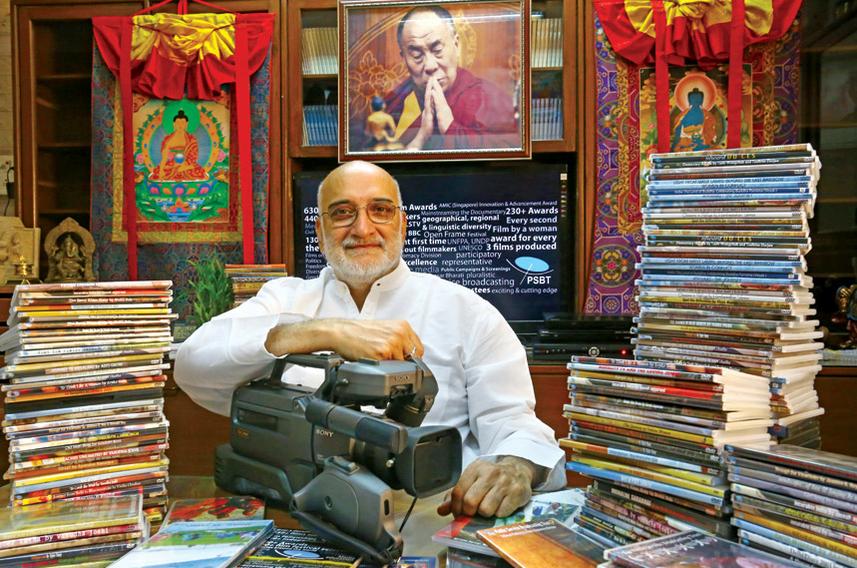

Rajiv Mehrotra, Managing Trustee, Public Service Broadcasting Trust (PSBT), is a media all-rounder. Radio, television, filmmaking and writing — he has done it all.

He was only nine years old when he went behind a mic to host a children’s show on All India Radio, Calcutta. Before he was out of his teens, he worked with broadcasting icon Melville de Mellow.

At Columbia University, where Mehrotra obtained an MFA in film direction, he was tutored by Czech director Milos Forman.

He went on to host 700 episodes of In Conversation, the longest-running talk show on public television in India. It brought him face to face with some of the world’s greatest contemporary thought leaders.

There aren’t too many people in this country who have seen the media evolve from quite as up close as him.

For the past 16 years, Mehrotra, as PSBT’s commissioning producer, has been tapping his experience and versatility to propel the mission of creating an inclusive platform for independent and diverse documentary films in a country where fresh, alternative media voices have been pushed into a corner.

A few years ago, Mehrotra tried to revive In Conversation on a private television channel. He did four or five episodes but it did not work. An image consultant was called in and he was told that he needed a makeover. Mehrotra chose to bail out. He wasn’t going to play the game by rules he didn’t believe in.

He has been equally unbending in the way he has steered PSBT. He has kept the trust afloat for over a decade and a half in the face of many challenges, fighting tooth and nail not to let external pressures throw him off his path.

“PSBT,” says Mehrotra, “is committed solely to the cause of independent documentary filmmakers and is not driven by any agenda related to profit or propaganda.”

PSBT’s guiding principle, he asserts, is to bring to the fore stories that need to be told, promote diversity of voices in the independent documentary space and highlight issues and themes that do not find their way into the advertising-dependent mainstream media.

PSBT was created with the support of Prasar Bharati and Doordarshan. The national broadcaster not only helps financially, it also provides PSBT a weekly platform to telecast its films.

“The Prasar Bharati CEO (Jawhar Sircar) is on our board of trustees,” says Mehrotra. “So everything that PSBT does is completely transparent.” The board, chaired by veteran filmmaker Adoor Gopalakrishnan, includes luminaries like Shyam Benegal, Fali S. Nariman, Sharmila Tagore and Kiran Karnik.

Free spirit

As the stranglehold of corporate entities increases on cinema, and both the message and the messenger are constantly manipulated to serve the needs of the market and the state, the battle to ensure greater visibility for independent documentaries has only gotten more arduous.

Since its inception in 2000, PSBT has been helping filmmakers across the country document reality in all its diversity: a mission that is now up against mounting odds.

But Mehrotra, an award-winning documentary filmmaker himself, hasn’t given up the fight. If anything, he has redoubled his efforts to further the PSBT cause and extend its life.

“Our production budgets are modest,” says Mehrotra. “As a result, filmmakers have to cut corners, which tells on the technical quality of a film.”

PSBT’s revenue generation is limited. Mehrotra points to the fact that the government retains 60 per cent of the royalty of a film. Any money that is made by Doordarshan goes into the Consolidated Fund of India and cannot be ploughed back into film production. PSBT has thus far survived solely on five-year grants handed out by the government. The current tranche is on its last legs.

“We share the rest of the royalty that accrues from a film with the filmmaker. We, therefore, do not have enough money to promote our films aggressively,” he says.

“I’ve been suggesting,” says Mehrotra, “that PSBT be given a bigger sum of money to begin with, which can be progressively reduced until it is down to nil in the 10th year. If we do not become self-sustaining by then, we will wind up and leave it to others.”

PSBT has so far supported and mentored more than 630 films, scooping up over 230 awards at home and abroad. Most important, the trust has helped over 400 first-time filmmakers cut their teeth in the profession.

PSBT now has 45 National Awards in its kitty. “Over the last year alone, our work has been selected at more than 200 film festivals, travelling from Thiruvananthapuram to Kuala Lumpur, Pakistan and Nepal to Oberhausen and Rotterdam, among other places,” Mehrotra points out.

He adds: “These films won 28 awards (in the past year). Three of our films were selected in the Indian Panorama — Benegal’s New Cinema (Iram Ghufran), What the Field Remembers (Subasri Krishna) and Jai Ho (Umesh Aggarwal). A record 14 films were selected at the Mumbai International Film Festival in January…”

At this year’s International Documentary and Short Film Festival of Kerala held in the second week of June, PSBT had seven films — Avadhoot Khanolkar’s Bade TV Wala, Sidharth Srinivasan’s Bahurupiya, Rajdeep Paul’s Mrinal Sen — An Era in Cinema, Nandan Kudhyadi’s Srinivasa Ramanujan: The Mathematician and his Legacy, Biju Toppo’s The Hunt, Ruchi Shrivastava and Sumit Khanna’s The Man Who Dwarfed the Mountains, and Gaurav Saxena’s Until Space Remains: The Dalai Lama and India.

While many impediments still remain, not the least of which are limited budgets and the resultant dependence on low-end technology, Mehrotra’s persistence has been crowned with many successes that have gone beyond just awards and festival selections.

A UNESCO report has lauded PSBT for offering “an innovative model for developing a shared public culture of broadcasting focused on diversity, accuracy, impartiality and marginalised audiences”.

PSBT films have a weekly slot on Doordarshan, a window on NDTV has been revived, and selected documentaries from its library are now also being premiered on the Epic Channel. “We have delivered 52 films a year to Doordarshan since 2001. We haven’t ever missed a single slot in all these years,” says Mehrotra.

“We have had significant success in the matter of delivering quality, but we haven’t yet had the kind of impact that we expected because of the limited reach of our films,” he admits.

“We would have also liked to achieve wider international exposure. Technically, PSBT films are low-end. We use technology that went out of vogue over a decade ago: DVC Pro 50 when the rest of the world is using high-definition and 4K,” Mehrotra admits.

Pioneer and mentor

PSBT operates out of a basement office in New Delhi’s East Nizamuddin. Much like the man who heads the operation, it has an understated but purposeful air about it. For independent documentary filmmakers across India, especially those that are seeking to start out, this is the go-to address.

“There is no entity like PSBT in this country,” says filmmaker Sidharth Srinivasan, who recently made a documentary produced by Mehrotra, Bahurupiya. “Its budgets may be low, but PSBT commissions films by genuinely independent first-time directors.”

“What is most impressive is the amazing diversity of themes that the PSBT films tackle,” says Srinivasan. “Each film that they commission is a unique beast.” In a country seduced by the familiar and the formulaic, that is no mean feat.

Mehrotra admits that in the initial years, filmmakers would approach PSBT with themes that they thought were in favour. “Over the years, we have tried to dispel that and encourage a wider range of ideas and approaches,” he says.

Says Mehrotra: “I would like to believe that PSBT has played a key role in energising the independent documentary space in India by unleashing 400-plus new filmmakers into the profession.”

“Two-thirds of the films commissioned by PSBT have been made by first-timers and starting out filmmakers,” he adds. “So we are adding some value to independent documentary cinema. Our funding is evenly spread across the country although we do not have any zonal quotas.”

PSBT’s slate covers a wide range of subjects and styles. The films deal with freedom, gender, environment, conflict, sexuality, livelihood, arts and crafts, globalisation, urbanscapes, culture and tradition, among other themes.

At one end of the spectrum are experimental films such as Vipin Vijay’s Vishaparvam, a video essay that explores layers of images through dialogues with a toxicologist, a convict, a traditional healer and a herpetologist: Ranjan Palit’s In Camera, which probes the cameraman’s art and craft from a personal standpoint; and Avijit Mukul Kishore’s Vertical City, a visual take on Mumbai’s ‘dystopic architecture’.

At the other end are activist films like Kavita Bahl and Nandan Saxena’s Candles in the Wind, about the widows of farmers in Punjab who have committed suicide; Subasri Krishnan’s What the Field Remembers, which revisits the site of the 1983 Nellie massacre; and Biju Toppo’s The Hunt, which investigates gross human rights violations in the Maoist areas of Jharkhand, Odisha and Chhattisgarh.

In between, of course, there is a host of other genres of documentaries represented by films like Akanksha Joshi’s Earth Witness, in which four ordinary people reflect upon climate change and how it affects their lives and livelihoods; Diya Banerjee’s The Hope Doctors, set in two hospitals that experiment with laughter as therapy; and Harjant Gill’s Roots of Love, which, through interactions with six men ranging from 14 to 86, documents the changing significance of hair and the turban among Sikhs.

PSBT also provides a platform for the exploration of personal spaces as in Sukanya Sen and Pawas Bisht’s A Body That Will Speak, which follows four women — a filmmaker, a university student, an entrepreneur and a radio jockey — in a bid to understand how body image plays out in daily lives; and Sridhar Rangayan’s Purple Skies, which probes the lives of lesbians in India.

Given the many successes that PSBT has registered, the brain behind the trust should have been going to town with his achievements. But pretty much like his workspace, his work isn’t easy to spot from the outside. But enter the PSBT office — it is run by just a handful of people and isn’t exactly a beehive of activity — and you know that this not-for-profit isn’t just another funding agency for documentaries.

PSBT has created “an independent, participatory, pluralistic and democratic” platform aimed at empowering documentary filmmakers to think out-of-the-box and pursue alternative modes of expression.

The profit-seeking corporate media and sanitised government-mandated information channels are off-limits for stories that address ticklish themes and raise uncomfortable questions. PSBT steps in to fill the breach.

“Ours has been a successful model,” says Mehrotra. “We’ve mentored new filmmakers and given them a platform for self-expression and capturing India’s diversity.”

Those in the know, of course, need no reminder: they are fully aware of the impact of PSBT’s work. As Mehrotra sees this writer off at the end of the interview, he insists that the focus of the write-up should not be on him alone. “This success story has been built in unison with talented filmmakers from around the country. They are just as important. As a Buddhist, I would recommend the Middle Path,” he says.

It is indeed the Middle Path that Mehrotra treads that has enabled PSBT to achieve many of its goals. Not all of them, by his own admission, are great films. But they have all been fired by a spirit of freedom and enquiry.

“That is what we believe in. We let filmmakers experiment without being bogged down by the fear of failure,” says Mehrotra. “We’ve built in a failure rate. We encourage filmmakers to take risks because even if they fail it isn’t the end of the world. Only by taking risks can they expand their boundaries.”

“We do not mind if a film does not shape up well,” says Mehrotra. “We give suggestions through a mentoring process, but we refrain from giving negative feedback to a filmmaker.”

Even in the case of filmmakers who are “dishonest” and misuse the budgets allocated to them, PSBT does not get into a confrontation. “We do not touch them again,” says Mehrotra.

“We have a full-fledged mentoring process. We vet proposals, scripts, rough cuts, revised rough cuts and finished films. But we do not impose our views on the filmmakers. We encourage divergent views to emerge. We let the filmmakers take the final call,” says Mehrotra.

Driven by passion

But, to some established documentary filmmakers, the PSBT model might seem a tad flawed, especially owing to the budget constraints.

Says Kavita Bahl, co-director of Candles in the Wind: “With the budgets that PSBT provides, you cannot do justice to a film, especially if you have to shoot at multiple locations and travel there more than once.”

“Today, filmmaking has moved to the digital domain, so the footage has to be graded. Costs of production have gone up but the budgets have stagnated. We had to dig into our own pockets to complete Candles in the Wind,” says Bahl.

“The PSBT model now works primarily for new filmmakers who are looking for a break,” she says. “For them the low budgets might not be such a big problem.”

But all the problems notwithstanding, PSBT soldiers on, driven by a combination of passion and enterprise. “Our model works because our filmmakers make films that they are passionate about. So there is always something in them,” he says. “We are the only ones who sanction budgets without demanding bank guarantees. Our model is based on trust.”

While PSBT’s films have travelled around the globe, Mehrotra has himself been to only one festival – INPUT 2015 Tokyo, where debutante Priya Thuvassery’s The Sacred Glass Bowl, which explores the rules of chastity and virginity applied to women in Indian society, was screened. “We are cash-strapped and so cannot afford trips to film festivals,” he says.

That PSBT’s films have, to date, won 230-plus national and international awards, besides earning over 1,300 film festival selections across the world, is a measure of the efficacy of its quality control processes.

Every September, PSBT also hosts the annual Open Frame Film Festival and Forum, where it showcases its own films besides presenting a selection of titles from INPUT (INternational PUblic Television). The weeklong event includes professional and student workshops and panel discussions and colloquiums.

With its films, PSBT has been successfully cutting through the clutter and cacophony created by private television channels and government-controlled information avenues and opening out into a space where the spirit of unfettered creative expression informs documentary filmmaking. The result has been an incredible output of films.

Says veteran documentary maker Arun Chadha, who has thus far made three films for PSBT: “They are a great ally for filmmakers who want to explore themes that others are not interested in touching. Conventional producers back only safe and tested ideas.”

In 2011, Chadha made the National Award-winning Mindscapes… of Love and Longing for PSBT. The film deals with the sexual needs of the physically challenged. “I met a few producers who rejected the idea outright. They felt it would be difficult to pull off. But not PSBT,” the filmmaker says.

All the filmmakers that PSBT has collaborated with are independent. No production companies or middlepersons are involved in its projects. Two-thirds of the filmmakers have been first-timers, while 50 per cent of the projects PSBT has funded have been helmed by women.

The latest in the long line of award-winning PSBT films is The Man Who Dwarfed the Mountains, which was adjudged the best environment film by National Awards jury this year. This was PSBT’s 45th National Award and Mehrotra’s 28th.

Directed by Ruchi Shrivastava and Sumit Khanna, The Man Who Dwarfed the Mountains celebrates the spirit and philosophy of environmentalist Chandi Prasad Bhatt, one of the pioneers of the Chipko movement.

“PSBT has won an award every two films,” says Mehrotra. “Our films have been lauded by professional juries around the world.”

The accolades notwithstanding, survival hasn’t been easy for PSBT, which depends solely on a government grant. “Up to 75 per cent of our budgets are spent directly on film production, five per cent on dissemination and 15 per cent on operating costs,” says Mehrotra.

“We work at 12-15 per cent margin,” says the trust’s managing trustee and commissioning editor. “Most NGOs operate at 30 per cent.”

Srinivasan, whose feature film in 2010, Pairon Talle germinated when he was working on An Outpost of Delhi, a PSBT-produced documentary on the indiscriminate urbanisation on the fringes of the Delhi, believes that the work that Mehrotra and his team are doing is absolutely vital in the Indian context.

He says: “One wishes that they had greater resources and bigger budgets, but who else is commissioning independent documentaries today as a form of self-expression?”

PSBT’s films are probably still not seen as widely as they deserve to be. Nor probably is its voice heard as loudly as it should be. But the sheer volume of its output has definitely widened the horizons for independent documentaries in India.