The Northern Ridge is the smallest part of the urban forest in Delhi

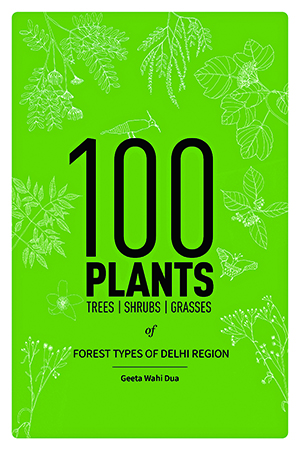

Some native landscaping in Delhi with a 100-plant guide

Civil Society News, Reviews

AS cities expand, they desperately need greening to save them from being concrete jungles. But what kind of greening should it be? Decades of growing just about anything, often merely because it looks good or has been passed down over the years, has resulted in costly ecological confusions. Why should plants and trees that need a lot of water be growing in an arid zone, for instance?

With climate change now more visible than ever and the environmental footprint of a city cause for concern, it has become common to talk of planting native species that suit local conditions and are less demanding. But what are these plants and how can they be weaned back into an ecosystem from which they dropped?

Even for those with the best of intentions, it can be very confusing. Making a beginning is not easy, let alone the wholesale transition that cities seem to need. Kind handholding is in order, but for that angels are needed who will do the homework, point in the right directions and even be available for ongoing advice.

Geeta Wahi Dua is one such blessed intermediary who has put together a slim volume, 100 Plants, which is about the trees, shrubs and grasses which belong to the different forest types of the Delhi region.

Geeta Wahi Dua is one such blessed intermediary who has put together a slim volume, 100 Plants, which is about the trees, shrubs and grasses which belong to the different forest types of the Delhi region.

To be precise, she has identified 60 trees, 24 shrubs and 16 grasses. Why just 100 plants, you might ask. It is because precision is required. Plants need to be identified, matched to soil types and understood for their functions. It is better to make a useful selection.

Wahi Dua’s book primarily serves as a manual. Don’t expect to spend time in bed reading the stories of plants and habitats. It is meant for landscape architects who know they should be going native but aren’t sure how they can get started.

Wahi Dua is a landscape architect herself. She edits and runs LA Journal, which is for landscape architects, with her partner, Brij. They also do other interesting things like bringing out a series of green maps of Indian cities.

The need to focus on plants arose during online classes she was giving to young landscape architects. They wanted to use native species but were short on the basics and were seeking a guide.

Wahi Dua says: “The book is in response to an increasing awareness among development authorities and spatial designers about the role and significance of native plants in creating sustainable and experiential urban spaces.”

Wahi Dua says: “The book is in response to an increasing awareness among development authorities and spatial designers about the role and significance of native plants in creating sustainable and experiential urban spaces.”

“The plants have been selected on the basis of the diversity of the eco-zones to which they belong — riverside, plains, hills and lowlands. Also taken into account is their adaptability to urban contexts and visual attributes,” she says.

Looked at this way, Delhi seems very different. We generally regard it as a city full of automobiles, congested housing and chaotic neighbourhood markets.

What has gone is its integration with nature. Plants are vital to this original identity. They represent soil quality and water resources. They are the sentinels of an entire ecosystem consisting of birds, animals, butterflies, bees, fungi and more. Cities that have decisively changed can’t come back in their earlier avatars. But bringing back plants that restore some of those contexts can soften the blow of urbanization.

Reminding Delhi of its original topography, natural wealth and sustainability has been creatively tried before. The Sunder Nursery is a flourishing example of different agroclimatic zones being brought alive. So is the Aravali Biodiversity Park on the border of Delhi and Gurugram. Both seek to revive lost natural systems.

These are undoubtedly laudable efforts. Unfortunately, they haven’t received as much recognition and replication as they deserve. They are also limited in their scope of influencing practice. The city continues to change this way and that.

|

| A large nursery of native plants at the Asola Bhatti Wildlife Sanctuary in Delhi |

Wahi Dua’s book goes directly to practitioners who really do want to make a difference in their professional lives. It is primarily a manual that a landscape architect can refer to in real situations. Additionally, it broadens horizons and increases knowledge. But the real opportunity it taps into is in changing practice. This holds out the hope of making a difference cumulatively over time. For cities to change architects first need the values and then the knowledge that will make them better urban spaces for future generations.

Wahi Dua tells us that “Delhi’s natural flora largely belongs to the Northern Tropical Dry Deciduous Forests and Northern Tropical Thorn Forests with some sub groups. These each have microhabitats of their own.”

There are four regions consisting of the Kohi, which is the Aravali hills consisting of the southern, central and northern ridge. The Bangar, which is the central flatlands, the Dabar or the low-lying areas, and the Khadar, which is the riverside. The Yamuna has always played an important role in the ecology of Delhi.

The trees, shrubs and grasses are listed with their local names, botanical names, descriptions, how they improve the environment, ecological role, ethnobotanical uses and, of course, possible design functions.

For instance, at random, we know that the bargad is an evergreen with an elliptical canopy. It has smooth leaves with figs. It needs large open areas to grow. It works as a buffer against pollution and is drought tolerant. Birds and insects like it. Because of its size and need for space, its design uses are limited.

Or, among shrubs, take the kamini. It is an evergreen. It has dark green and glossy leaves on ‘woody’ branches with small white fragrant flowers which appear in clusters along with green berries. It has moisture-holding capacity. Its white flowers and their fragrance make it useful for ornamentation.

We don’t know if 100 Plants is adequate. It might be falling short in various ways. Its success will be decided by how effectively it will be used. Refinements will undoubtedly be made. But looking at cities afresh and enabling professionals like architects to shape their future better is a laudable objective. So, this is a beginning well made.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!