An elderly vendor in Chinatown serves up a steaming hot breakfast of dumplings

Inside Kolkata’s Chinatown

Aiema Tauheed, Kolkata

On a sultry Sunday morning, eight of us gathered at the Metro’s Central Station gate to embark on a walk to Kolkata’s famed Chinatown. We trooped down Sun Yat Sen Road behind our guide. He remarked in passing that the esteemed Sun Yat Sen was the equivalent of Mahatma Gandhi for the Chinese.

It was peak breakfast time, between 6 and 9 am. What better way to satiate our hunger for adventure than with a hot Chinese breakfast in the historic lanes of Tiretta Bazaar.

Our group comprised a doctor, a businessman, two Indian Forest Service officers, and some others. Our guide was Avijit Dhar Chowdhury of Kolkata Explorers, a division of Green Step Tourism which specializes in heritage and experiential tourism.

We arrived at what looked like just another bazaar. The gritty pavement was dotted with makeshift stalls selling everything from flowers to fresh fruit to raw fish and chicken and steaming plates of food.

We stopped in front of Pou Hing, a restaurant, where a frail, woman sitting on the pavement greeted us with a gentle smile. Chowdhury said that she was the oldest vendor there. “What would you like?” he asked us. Responses ranged from “anything with pork” to “chicken is fine” and “only veg dumplings, please.”

A cloud of steam billowed into the morning air as the lady slid open the lid of her large container and filled plates from separate compartments inside. “I have been making these with my own hands for over 40 years,” she remarked with a proud smile.

Lipika, an Indian Forest Service officer, took a bite of her chicken-fish dumpling, savouring its flavours. Her best friend beside her tucked into a plate of vegetarian dumplings. “My office is just around the corner,” Lipika said with a smile, “but I’ve never had the chance to come here for breakfast. I’m thoroughly enjoying this.”

Mohammed Saddam, who usually splits his time between the gym and his family business, nodded in approval. “This is so fresh and so much better than what you get at high-end restaurants,” he said as he bit into a bao.

Just a few steps away sat Bobby Young, serving dishes made from old family recipes: fishball soup, meatball soup, and a range of other items priced between `60 and `120.

Her food stall wasn’t just a local favourite. Frequented by food vloggers, it has found fame on social media. She eyed me and my phone, quickly assumed I was another vlogger fishing for footage and briskly shooed me away, all the while juggling a flurry of large orders.

|

|

Inside a Chinese place of worship |

Umami flavoured bowls of soup from her shop were set down with small bangs on a table with no chairs. We gathered around, standing shoulder to shoulder, discussing shared meals, communal eating and the city’s disappearing trams as we slurped.

With our tummies full, we were now truly energized to forge on ahead. The colour red followed us at every step. “It is an auspicious colour in Chinese culture. That’s why masks in the dragon dance are red,” explained Chowdhury.

Our first stop, Sea Ip Church, has been declared a Grade 1 heritage structure by the West Bengal State Heritage Commission. “That’s why we have the blue plaque here,” he pointed out the blue disc at the entrance. “Being Grade 1 means you can’t make changes to the exterior or major alterations inside.” Most Chinese temples or churches follow Buddhism, Christianity and folk religion.

On the ground floor stood a modest table with chairs around it. One wall held an abacus, an ancient Chinese counting tool, and photo frames displaying a Chinese gazette and other Mandarin texts. At the centre of the wall two well-known faces beamed down at us: Sun Yat Sen and Mahatma Gandhi, side by side. “Both are seen as father figures,” he said. “One is the Father of China, and the other the Father of India. The furniture you see is from that time,” he added, as we climbed a flight of stairs.

Reaching the first floor, we spotted the serene figure of Guanyin — the Chinese Goddess of Mercy — reposing gracefully amidst other idols. Suspended above her was a magnificent, intricately carved wooden sculpture.

“That is carved out of a single piece of wood,” Chowdhury pointed out. “The Chinese were excellent carpenters.” Painted in gold, it showed a cluster of figurines standing aboard a large ship. “It shows them arriving by sea, sailing to India for trade. It reflects their identity as a trading community,” he explained.

In an adjoining room stood the imposing figure of the Chinese God of War, Guan Yu. Clad in flowing robes, his expression was stern and watchful. Once a real-life general during the Han dynasty, he became renowned for his courage and martial prowess, making him a paragon of loyalty and righteousness in Chinese culture.

On the breezy balcony of the church, where the fragrance of incense wafted, Chowdhury related its story. The church, he said, was established in 1905, the year Bengal was partitioned by Lord Curzon. After protests, the partition was annulled and this church was erected as Bengal reunited. It replaced the original Sea Ip Church, built in 1882.

|

|

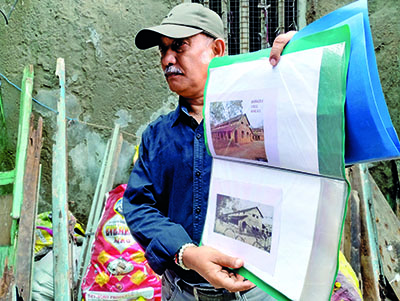

Avijit Dhar Chowdhury explains the history of Kolkata’s Chinese community |

Inside, we noticed caretakers bowing three times in prayer. “You’ll also see incense sticks in odd numbers — three, five, seven, or nine,” Chowdhury explained. The reason? Each bow signifies Dharma, Chakra, and Sangha — the central pillars of Buddhist faith.

“How do you light the camphor?” someone from the walk asked the elderly church keeper, Maria Teng. “The way you light up Om,” she smiled. “Everything is the same, just different systems,” she said. Maria, now 74, has been devoted to this church all her life. Her son has followed in her footsteps. Her grandson, however, has chosen a different path: “He’s 23 and works at ICICI bank,” she said with quiet pride.

Our second stop was Toong On Church. After climbing a flight of steps past damp walls, we gathered around a long table in the dimly lit prayer hall. “Below this hall was Kolkata’s first Chinese restaurant: Nanking. It attracted the elite from across India, including legendary actors like Raj Kapoor and Shammi Kapoor,” he said as his small audience gasped, visibly impressed.

Then, with the Chinese God of War watching over us, Chowdhury stepped forth and began relating the story of the church from scratch.

“Tiretta, often mispronounced as Tiretti, was named after Eduardo Tiretta, a Venetian who arrived in India in 1782 after setting Europe on fire,” he chuckled. “He was connected to Jacques Casanova.”

In the late 1700s, amidst Kolkata’s squalor with no roads, no sanitation, rotting corpses on the streets, he proposed a pucca market where hawkers could sell their wares.

With Warren Hastings’ permission, Tiretta Bazaar was built. But the venture led to his bankruptcy in 1787. It was bought by a European named Charles Wester, as recorded in the Calcutta Gazette. Four decades later, in 1827, another Gazette notice announced its resale. This time, it was bought by the Maharaja of Bardhaman.

And so the years rolled by. Empires shifted. Independence from British rule came in 1947. “Now this is under the Kolkata Improvement Trust (KIT),” Chowdhury said.

But how did the Chinese come here? We were teleported to a history class peppered with humour and dialogue. Ong Atchew was the first Chinese settler in Calcutta. He came from Guangdong in South China, arriving at Budge Budge (then Bajbaj) around 1778 while working on a British cargo vessel. “He was employed by the British as a trading agent of sorts. His job involved sailing from China with cargo, supervising its offloading on arrival, and then heading back,” explained Chowdhury.

Instead of returning to China, he got himself a large land grant from Governor-General Warren Hastings and set up sugarcane cultivation, at a time when India still imported sugar from Java. To run the operation, he brought across Chinese labourers from Guangdong, sowing the roots of Kolkata’s earliest Chinese community. The word for sugar, chini, traces back to this legacy.

As we made our way to the last church, we passed timeworn churches, curious nameplates, and flashes of red everywhere. Chowdhury explained the layered history of Calcutta’s Chinese community, whose migration began in the late 18th century.

“The Hubeis were teeth setters, Chinese dentists,” he began. “The Cantonese were initially ship fitters who by the 1950s transitioned into carpentry. The Hakkas were talented shoe makers and leather manufacturers.” He noted that they are mostly restaurant owners now. “Interestingly, none of them came to India to cook,” he said.

Finally, we stepped into the last Chinese temple, Nam Soon, with an open courtyard filled with trees. It looked straight out of a painting. Tony, the elderly caretaker, greeted us with an embarrassed smile.

There was darkness all around. “Taqdeer hi kharaab hai,” he said. There had been no electricity since last night, he explained. Still, with the glow of his phone’s flashlight, he led us in, pointing out every idol with care.

“In the old days, the poor and the needy worshipped him,” he said, stopping at a statue he called a king. “You’ll find him in every Chinese temple. Chinese businessmen still worship him.” The gold crown on the statue glinted in the dark. We stood listening, sweat trickling down our backs.

He dismissed any talk of challenges in maintaining the church. They didn’t want it declared a heritage site, was his contention. “If we accept heritage status, the government takes over. What the Chinese community wants is just a little privacy,” he explained.

The last few minutes were spent explaining the community’s move from Tiretta Bazaar to Tangra. We listened intently, for history had also explicated the flavour of food that lingered as the walk came to a close. ν

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!