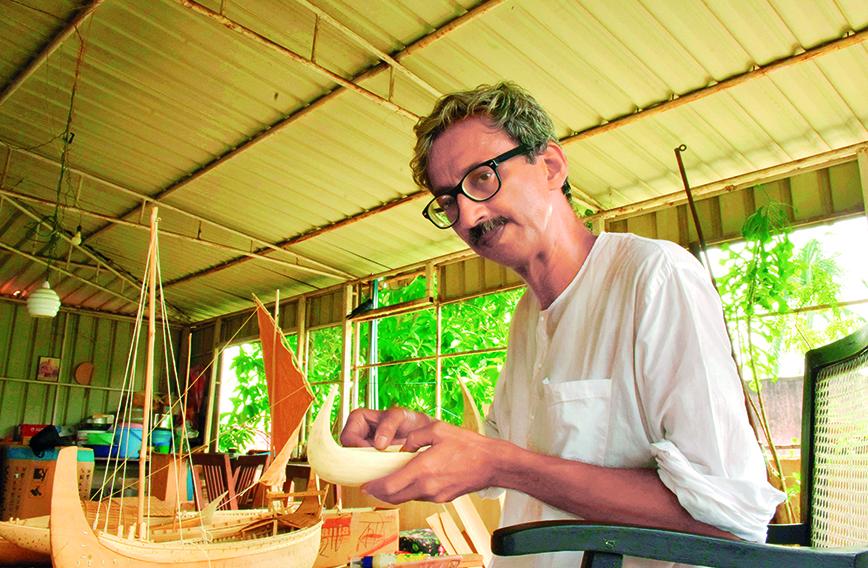

Swarup Bhattacharyya studies and builds boats to chronicle human evolution

Get the drift: The saga of Bengal’s ancient boats

Subir Roy, Kolkata

Every river has its own distinctive current, wave pattern, wind and tides. And rivers mean boats which predate the wheel, says anthropologist Swarup Bhattacharyya who has spent the better part of his academic life pursuing the saga of the boats of Bengal. If you wish to study the evolution of man in society in geographies where rivers predominate, a highly rewarding way would be to study the evolution of its boats which used the winds and the tides and the brawn of boatmen to get around the world long before mechanical boats arrived.

Riverine “Bengal”, as it was called before it was divided, resides in the delta that comes at the end of the north Indian rivers before they meet the sea. Its life is intricately linked with the boats that it has been using since prehistoric times to negotiate the rivers that criss-cross it.

Historically, migration of people was not possible without boats and once they came they enabled barter trade which was conducted through the exchange of surpluses. This happened long before money was invented. Bengal’s boats evolved so early and robustly that they have featured prominently in the narratives of medieval times. An early sketch book has a chapter on the “boats of Bengal”. Within Bengal boats have featured prominently in the terracotta panels that are found across the region.

Historically, migration of people was not possible without boats and once they came they enabled barter trade which was conducted through the exchange of surpluses. This happened long before money was invented. Bengal’s boats evolved so early and robustly that they have featured prominently in the narratives of medieval times. An early sketch book has a chapter on the “boats of Bengal”. Within Bengal boats have featured prominently in the terracotta panels that are found across the region.

Tamralipta, a port city in ancient India, was located on the coast of the Bay of Bengal. It has left behind an earthen toy boat which is similar looking to the boats excavated in Harappa. Thus, boats in a way linked and made India one from early civilizational times. But this chain of historical evidence was broken during British times when there was a gap in records. Coming up to the present, there are records of at least 50 types of boats currently in use in West Bengal. Bangladesh has records of 176 boat types.

Explaining why he finds the study of the boats of Bengal so engrossing, Bhattacharyya (51) says, “Bengal is heaven for those pursuing maritime ethnography.” He is a PhD scholar in the department of anthropology of the West Bengal State University. He is also associated with the Nehru Museum at IIT, Kharagpur and has worked as a senior research fellow with the Anthropological Survey of India.

The journey began, symbolically via boats if you like, with joining the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) project on boat typology and fishing communities of West Bengal and the Andamans to document the boats of Bengal. With this background, curating India’s first boat museum, work on which began a decade ago, naturally fell upon his shoulders.

Bhattacharyya makes wooden models of boats — some tiny and others a little larger. In 2006 he had an exhibition in Delhi. But it was in 2017 that he began crafting models on a regular basis. Then came the pandemic when he found all the time to focus on his passion.

It takes between 20 and 30 days to make a model and Bhattacharyya now has a personal collection of 20 such model boats. He would dearly like to have a permanent exhibition if he could find the financial support. But going forward he might also sell the models a piece at a time.

Among international authors, he mentions Sean McGrail who has written Boats of the World and Boats of South Asia which seek answers to the question as to why a particular type of boat came up in a particular region and then travelled to others. The South Asia book in particular covers different styles of boat making unlikely to be found outside the subcontinent. It also documents an array of traditional boats used in the subcontinent today for fishing and other coastal river tasks.

Bhattacharyya’s collection of his handmade boats

Bhattacharyya’s collection of his handmade boats

Today the ‘Patia’ boat is available only along a 15-km stretch of the Bengal-Odisha coast. But there is a relief of the Patia in the bhogamandap of the Jagannath temple in Puri. The Victoria and Albert Museum in London has a three-dimensional sculpture of the Patia boat which belongs to the 11th century. In the Indian Museum in Kolkata there is a 12th-century Patia relief which was found in Bhubaneswar. Clearly, boats connected Bengal and Odisha long before highways, railways and aeroplanes.

The Patia in use today is of course not the same as in early times. It has added a few planks over the past 800 years! This is a fine example of how boats have evolved, capturing the progress of human knowledge and the result of human ingenuity taking key articles of use forward. This work took Bhattacharya to Balagarh village near Kolkata on the bank of the Hooghly. He learnt a lot from this famous centre of boat-making and home to many of the fishermen of the Tiyor Rajbangshi caste.

In the process of his research Bhattacharya has found evidence of how boats have entered the human consciousness in Bengal. Today a child in Bengal will draw a boat on his own, but a child in Punjab will likely not; this is despite the fact that few children today manage to take a boat ride. His consciousness about boats comes from the illustrated material which is given to him by his elders with encouragement to draw what he likes. Where does the inspiration for the illustrations come from? It has been found that in the art colleges of West Bengal students will typically draw landscapes with boats in them.

How ingrained boats have become in the consciousness of the Bengali can be found from the fact that they share a platform with the other Bengali obsession, football. The Mohun Bagan club symbol is a boat. Things have been taken to an altogether different plane with the ruling Awami League of Bangladesh adopting the boat as its symbol. So the boat has been on an unending and uninterrupted journey in the Bengali consciousness from prehistoric times till today.

If boats hold hands with football and politics, then the creative arts cannot be far behind. The works of prominent Bengali litterateurs like Rabindranath Tagore, Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay and Bankim Chandra Chatterjee feature boats. A good example is Chatterjee’s novel Debi Chaudhurani. More recently, we have Manik Bandyopadhyay’s Padma Nadir Majhi and Samaresh Basu’s Ganga. Particularly noteworthy is the role that boats and boat journeys played in the life of Tagore. He had his own boats and one was named Padma, after the great river in Bangladesh, in which he travelled and stayed while looking after his zamindari in Shilaidaha. The boat was made by craftsmen from Dhaka for his grandfather, Prince Dwarkanath. Tagore did a lot of his writing while aboard the Padma.

Musical traditions like the Bhatiali and Sari all grew out of the lives of boatmen. Bhatiali songs are essentially love songs sung by boatmen in their loneliness when away from home. The Sari is a rhythmic song sung together by boatmen while rowing so as to make the task both endurable and enjoyable. As they rowed they created the music which the music directors of today use, not the other way around.

How did this great boating tradition evolve? The craft and skill of boat making was transmitted through the guru-shishya parampara system by master craftsmen to their apprentices. The key element that every youngster had to learn was the way to coordinate what the eye saw and the hands crafted through the metamorphosis that took place in the brain. Having picked up what the guru handed down, the apprentice chewed on it in his mind and innovated, then passed it on to the next generation. This is how the craft and, if you like, art evolved.

It is noteworthy that in this transmission of knowledge through generations, nothing was written down. The two occupations of boat making and fishing were originally carried out by the Chandal caste which is now called Nama Sudra. It belongs to the currently listed Scheduled Castes. The Chandals were in fact among the original inhabitants of Bengal. They traditionally had no formal education and skills were handed down by execution and observation. Although the Chandals formed a particular caste, people from any social group could join and become a part of the tradition.

In recent times there has been a large number of Muslims among Bengal’s boat people. Importantly, Brahmins have had nothing to do with boat making or sailing and the recording and transmission of the attendant knowledge. Thus such a powerful and distinctive tradition has been preserved and transmitted by people deemed to be illiterate and of lower caste!

But such people have as powerful and enduring emotions as any others. A boatman gets emotionally connected to his boat. He believes he is bringing into this world a beautiful daughter who will one day go to some other home after marriage. She is also a symbol of fertility as she starts her journey in the water and helps earn a productive living.

The boatman’s life has even earned him a place in the Bengali almanac. There is an auspicious day for starting to make a boat, Nouka Gathon, a day for handing over the boat to the client, Nouka Chalon, and finally the day the boat becomes water-borne, Nouka Jatra. Bhattacharyya is on a long and engrossing journey in the wake of the boat which is far from over.

Comments

-

Subhra Bhattacharyya - Nov. 7, 2023, 7:40 p.m.

Very interesting! Swarup is keeping the tradition alive... He has worked hard to achieve this perfection and accuracy in carving the detailed structure of the boats... I truly appreciate his work of art... Best wishes to Swarup and thanks to Mr Subir for bringing out this excellent article on a genius researcher.

-

SANJAY BASU - Nov. 5, 2023, 8:46 p.m.

An extraordinary presentation with excellent, appropriate design & description, this wonderful harmony of the socio-cultural evolution of civilization & the water- transportation mediums deserve strong patronage & sincerest appreciation.

-

Rajita Agarwal - Nov. 1, 2023, 9:09 p.m.

A very engaging read. So much can be gleaned from the history of boats. Hats off to Shri Swarup Bhattacharya's passion and dedication.

-

Anis Raychaudhuri - Oct. 30, 2023, 9:35 p.m.

Swarup Bhattacharyya has been pursuing this study with an exceptional zeal for years now. It is high time his work gains appropriate recognition and gets showcased in a museum. That will serve the coming generations by making knowledge and models available and will also support the boat-making tradition of Bengal.

-

Subhra Bhattacharyya - Oct. 30, 2023, 7:38 p.m.

Very interesting! Swarup is keeping the tradition alive... He has worked hard to achieve this perfection and accuracy in carving the detailed structure of the boats... I truly appreciate his work of art... Best wishes to Swarup and thanks to Mr Subir for bringing out this excellent article on a genius researcher.

-

Bibhabori - Oct. 30, 2023, 3:28 p.m.

Proud of you

-

Anindita Ray - Oct. 30, 2023, 9:25 a.m.

Proud of you ....... alwayzzzzz

-

Anindita Ray - Oct. 30, 2023, 9:25 a.m.

Proud of you ....... alwayzzzzz

-

Anindita Ray - Oct. 29, 2023, 9:48 p.m.

Proud of you ...... alwayzzzzz

-

Subrata Das - Oct. 29, 2023, 4:56 p.m.

Congratulations for the wonderful Publications

-

Parag Ray - Oct. 29, 2023, 2:31 p.m.

Dr. Swarup Bhattacharya is a very endearing , erudite person. He has the most impeccable story telling style. I had been witness to his growing passion from early youth and a zest to walk the uncharted road. His contributions are many, which include national and international research areas in anthoropology related to rivers and boats. My regards for a life well lived.