Medicines, sent by Doctors For You, arriving in Manipur

Done with your meds? You can pass them on to others

Sukanya Sharma

Decluttering is the order of the day. Clothes, books, shoes, cosmetics, crockery and such like are relatively easy to give away. But what about those medicines that one no longer needs and haven’t expired? What does one do with them? Putting them in the trash is a waste and passing them on to second-users requires medical supervision.

Sushmita Bhatia faced such a dilemma when her husband passed away. A whole lot of drugs had piled up during his long treatment. She began searching on the internet where she discovered Doctors For You (DFY). A phone call later she had arranged to pass on the depressing stash of medicines, reassured that they would now be in the hands of professionals who would put them to appropriate use.

“I read about a couple of others too but this organization seemed reliable, especially because doctors were running it at the forefront — that is what caught my attention first. I was also inspired by the founder’s profile, which made me choose to donate here,” she says. “With medicines, you have to be careful because there is always a risk of them falling into the wrong hands.”

Doctors For You was founded by Dr Ravikant Singh in 2007 in Mumbai to rush medical support to crisis situations. It could be a flood or an earthquake or the outbreak of some disease. DFY supports government services in such situations. It was a lifesaver during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Recycling of unused medicines is a natural extension of DFY’s activities. It happens in three ways: collection boxes at health centres, collaboration with other organizations and walk-in donors.

Dr Rajat Jain, DFY’s president, explains, “It is based on community participation — people who have leftover medicines which are due to expire within a period of three to six months can donate them. We sort them, create a pool and then use them for patients who visit our healthcare centres or during relief camps in crisis areas.”

For instance, recently in Manipur, donated medicines were added to the stock that was already being sent for aid. DFY’s footprint is pan-India. It has a presence in Pulwama, Patna, Guwahati, Dimapur, Bengaluru, Delhi, Mumbai and so on.

Among tie-ups with organizations, Goonj is one of the main partnerships. Goonj is better known for collecting old clothes and other recyclables. Medicines also come in and go to DFY for use.

Apart from its own health centres, DFY partners with government hospitals which are willing to take unused medicines. This is typically in a scenario when medicines such as potent or injectable drugs for complex medical conditions are donated (since such patients do not come to DFY clinics, they are better utilized if donated to government hospital set-ups).

“We have had people calling in to say their parents have passed away and they want the leftover medicines to go to a good place — where they know it will be used well,” says Rohini Wadhawan, a healthcare professional at DFY.

“A lot of things come in, there are adult diapers, painkillers, antibiotics, injections and vitamins,” she adds.

A recent example is of a donation consisting of diabetes medicines that were due to expire in three months. The team made urgent calls to find out where they were needed on a priority basis and the drugs were put to good use. “The most important area I want to work upon is setting up community engagement medicine banks in almost every city and in hospitals as well. Whenever a patient is discharged, there are a lot of medicines in their possession which are of no use to them and end up being wasted,” says Dr Jain.

“In fact, even in a regular household, sometimes six or seven tablets from a single strip go waste. I wish all of us could develop the habit of donating instead of wasting,” he says, likening it to the concept of donating used clothes or books in good condition.

|

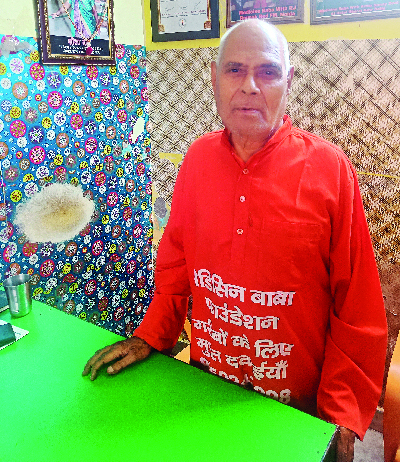

| Omkar Nath is called Medicine Baba |

Any conversation about medicine banks is incomplete without the mention of 87-year-old Omkar Nath, better known as ‘Medicine Baba’. Famous for walking around neighbourhoods of the capital in an orange kurta that bears his sobriquet along with his phone number, he goes from home to home collecting surplus medicines for the poor. Nath used to be a laboratory technician who, after retirement, found that he could make himself useful to society by recycling medicines.

“I have been doing it for the past 17 years. You will see me doing this for as long as I am alive,” he says.

His journey began in 2008 after he witnessed a Delhi Metro bridge collapse in Lakshmi Nagar that left four people dead. They were poor labourers who died because they couldn’t afford adequate medication. The tragedy had a profound impact on him and he resolved to devote his life to making medicines more accessible for the poor.

“My wife,” and he points to her garlanded picture above his desk, “thought I had lost my mind and didn’t speak to me for a few months until she saw my photograph in the newspaper one day, and realized I must be doing good work! She was very supportive after that.”

Medicine Baba operates out of a small, dilapidated set-up in Uttam Nagar. He rents this space for Rs 12,000 a month. He says he squirrels together the cost of his operation through donations and whatever little he can afford. There is a simple desk, a lone computer, shelves full of awards he has received for his work. A small room inside is brimming with tall racks full of medicines that have been donated.

A fridge for the injectables and perishable medical supplies such as insulin and human albumin is placed in a corner. There is a small opening in one of the walls — a window where the action takes place. People from vulnerable backgrounds line up with their prescriptions to collect medicines. This is one way in which the poor access his collection.

|

| An elderly patient collects medicines from Medicine Baba’s store |

Other ways include Nath’s visits to government hospitals like AIIMS and Safdarjung, trusts like the Ramakrishna Mission and old age homes.

Until last year, he would call for medicines on foot despite a problem with his leg. He has now switched to going on his bike, which one of his workers drives for him.

“I have one goal and that is to serve the poor — sewa brings me satisfaction,” he explains. “I am not a social worker or activist. I am a beggar. Just like any other beggar or fakir, I am a beggar for medicines. That is how I see myself and I have no shame in saying so.”

To donate, one can either approach him directly when he is on his visits to neighbourhoods or medicines can be dropped off at his office in Uttam Nagar. His small team has also set up collection corners across the city — gurudwaras like Sikh Sangat in Green Park, crematoriums and some private clinics, where medicines can be donated.

He now receives medicine donation packages worth lakhs of rupees from all over the world, including countries such as France, England, Germany, and the US. A recent delivery from the UK was a box of 200 colostomy bags (a pouch used to collect waste from the body after surgery). These were then donated to the gastroenterology department of a government hospital.

The SCERT English textbook for Class 10 in Chhattisgarh features him. He proudly shows the page and says, “Being a small part of the school curriculum is a bigger award for me than the Bharat Ratna!” His card bears the slogan he has coined himself: ‘Bachi dawaiyaan daan mein, naaki kudedaan mein’ (leftover medicines should be donated, not discarded). His dream is to have a medicine bank in every district. India’s size and population worry him but he doesn’t lose hope. Explaining his cause, he says, “We all have to die one day but my wish is for no one to die because of lack of access to medicines.”

ShareMeds Foundation came up five years ago when a Mumbai-based family realized that the problem of surplus medicines and subsequent wastage was a reality in most homes. To bridge the gap between surplus and lack of access, the foundation began medicine collection at their main centre in Mumbai and has donated more than 30,000 medicine items over the years. Medicines can be donated at their office.

Ripa Sanghvi, co-founder, says, “The problem is real so people are more than happy to contribute to the ShareMeds initiative, which is heartwarming to see. It is quite easy to collect unused medicines but the real challenge is distribution.” It would be ideal if the medical fraternity and pharmaceutical companies also do their bit, so that the medicines reach the right people, says Sanghvi.

The internet shows there are other compassionate crusaders working for this cause. Uday Foundation, founded by Rahul Verma, is based in New Delhi’s Sarvodaya Enclave and accepts medicines and medical equipment in usable condition like wheelchairs, walkers and canes. These can be donated at their office. Then there is the Mallikarjuna G.-founded SERUDS (Sai Educational Rural and Urban Development Society) in Kurnool, Andhra Pradesh. Medicines are mainly donated in four major areas — distribution in slums via medical camps, old age homes through personal visits, health camps in under-served areas and emergency relief. Janaseva Foundation in Pune, Hope Kolkata Foundation in Kolkata and Saath Charitable Trust in Ahmedabad also accept medicine donations.

Comments

-

Chandralekha Anand Sio - June 8, 2024, 10:27 p.m.

This is a most wonderful system of giving medical aid to the less fortunate. Medicines can be very expensive and thus unaffordable by many.Instead of throwing away or keeping medicines not required ,the collection and distribution of these is a wonderful idea. To make this a success we do need several charitable minded people.All the best to those who have already taken the initiative and doing such good work.