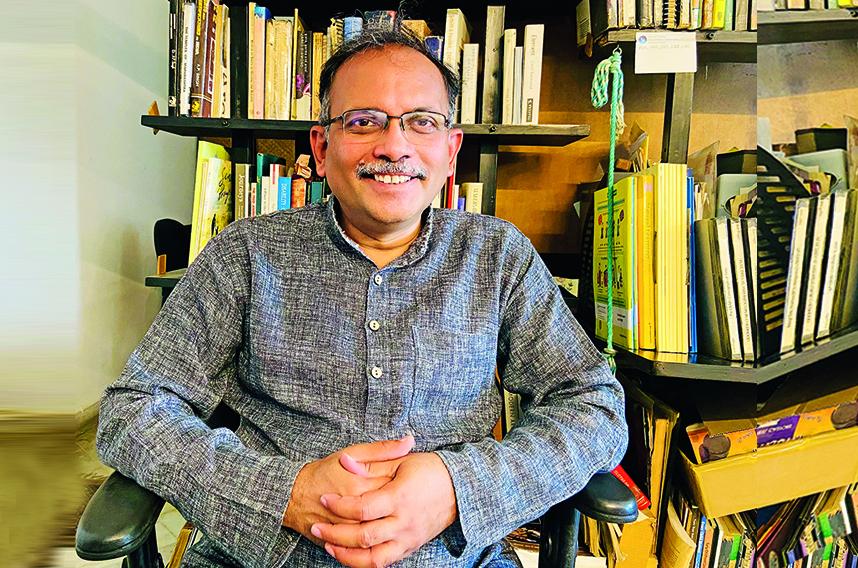

Kabir Vajpeyi: 'Rudimentary facilities for making the anganwadi worker effective are lacking'

‘We have not understood the value of child development’

Civil Society News, New Delhi

For the past seven years, Kabir and Preeti Vajpeyi have been involved in bringing architectural and design changes to anganwadi centres so as to make them more child-friendly and inclusive.

With the New Education Policy’s emphasis on early childhood development, their work acquires yet greater significance. More than ever, anganwadis now need to be vibrant and creative places where pre-school children begin the process of learning and development.

The Vajpeyis are public-spirited architects who have in the past used their training to transform government schools through low-cost solutions. All of 26 years ago they were involved in a programme in Rajasthan to enhance learning in government schools at minimum cost. From that effort came BaLA or Building as Learning Aid, a programme widely adopted by state governments.

As in BaLA for schools, the Vajpeyis have explored design solutions for anganwadis, which are mostly neglected and lacking in infrastructure.

To understand the challenges involved in improving anganwadis, Civil Society spoke to Kabir Vajpeyi in an extensive interview, an extract from which appears below:

You have been working for several years on the infrastructure needs of anganwadis across states. In what condition do you find anganwadis in general?

I am first going to talk about the state of anganwadis as an institution, based on my experience. The anganwadi centre is the dissemination point of the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) scheme.

The ICDS programme is a very important programme. It has been conceived more holistically than many others. It looks at child development in connection with so many critical aspects.

It addresses the early-age child, the infant, the mother, the caregiver, the family, and, even before that, the adolescent girl who might become a mother later.

But the focus and attention such a well-conceived programme deserves is lacking. You don’t often see focus in the programming or in the financing or on the ground.

So what do you think is lacking in the implementation of the concept?

I think it is the intent to engage with the issue of child development holistically. We have not really understood the value of child development and what it means in the later phases of life for everyone.

There are studies which show that if you invest wisely in the finer details of implementation and monitor quality, the returns are nine to 15 times for every rupee spent. Good programming translates into effective childhood development, education, health, employability, livelihood and so many things. So it has a huge economic spin-off.

What are the three or four things that you think must be quickly done in terms of implementation?

I think engagement is needed to really develop a child. The capacity of our anganwadi workers needs to be enhanced and augmented.

So are you saying they’re not trained enough?

They come with experience, but they need more systematic knowledge which they can use to transact with children on the ground. For instance, they may often think children are supposed to be very disciplined and sit quietly. I mean, at the pre-school stage children are meant to explore their environment and not sit quietly and be disciplined.

Rudimentary facilities for making the anganwadi worker effective are lacking. Often, she fights a lone battle. At times, for days together, she may be bringing food from her home. There might be several things she might be doing out of sheer dedication and affection for the children. The state of anganwadis is the culmination of several shortcomings in the system. Unfortunately, the blame and focal point is on the anganwadi worker.

Nutrition is key to the programme, but if you look at the kitchen and where the food has to be stored you will often find rodents, dampness and all kinds of things percolating there. Why? Because nobody in the system ever thought of securing it properly.

Take the simple example of water. We did a study in Rajasthan, West Bengal, Bihar and Maharashtra. We found that the local panchayat or municipal authority was not fulfilling its responsibility of providing water to the anganwadi. As a result, the anganwadi worker or her helper had to fetch water from her personal resources. She’s supposed to be a voluntary worker who gives four to six hours of her time every day. But 25 percent of that time is spent in organizing water instead of being focussed on the core activities of the anganwadi.

Under the national curriculum framework for early childhood care and education, outdoor activities are given high importance. They involve play, engaging with nature and so on. They’re so critical at that stage. Such activities are not just about physical development but about social, emotional, cognitive development. You develop self-confidence. You develop social engagement by way of playing. You learn to negotiate.

Now, the significance of that outdoor space is just not understood. It is not for the anganwadi worker to first understand it. It is for the system, for the people who are sanctioning, financing and planning the anganwadi to understand it and then only can it percolate.

You are saying that the programme needs to be better conceptualized and managed?

It is well conceptualized. But, yes, management needs attention. There’s another aspect to the anganwadi story which is alarming. It is corruption and it is across states. Every anganwadi worker is supposed to pay the higher-ups and the money comes from the food they buy. Imagine, we are stealing from the very food that is meant for the youngest members of our society! This is outright shameful and outrageous. How do we stoop to such a level?

In which states is this happening?

I mentioned Bihar, West Bengal, Rajasthan and Maharashtra. From the overall ration amount that she gets, the anganwadi worker is supposed to pay a cut to the higher-ups. I feel it’s the system which is responsible for this, and not this lady, the anganwadi worker. She is forced to do this.

What is the relationship between infrastructure, which is your domain, and the successes and failures of this programme?

What we’re trying to do in different states has to do with the infrastructure at an anganwadi level. But, yes, certainly we try to look at the linkages. We are adapting and augmenting existing anganwadi spaces so that all services under the Integrated Child Development Services programme are delivered more effectively.

I’ll give you an example. If we find that there is severe malnutrition in a particular district or block or project area, we try to identify deficiencies from the infrastructure perspective.

My take would be, what can we grow on the anganwadi premises to take care of some of this malnutrition? What nutrients are deficient which can be grown at home and on the anganwadi premises using whatever minimal resources are available?

Do you get to connect larger health concerns with the lack of infrastructure?

Not always, but I’ll give you an example from Rajasthan. We discovered that many of the adolescent girls who were also going to an anganwadi for counselling and other support were experiencing urinary tract infection.

There were two reasons. One was that the anganwadi was located in the school, where the sanitation facilities were not good. So these girls were either not coming to the anganwadi when menstruating or, when they were, they were holding their urine because the toilets were so bad. They couldn’t go back home to use the toilet because that would mean having to cover one or two kilometres.

There was a toilet there, which was part of the anganwadi system. But it was not designed for use by multiple users such as mothers, very young children and the adolescent girls. An investment had been made in the toilet but it was dysfunctional. So while the programme is clear that toilets are needed for children, adolescent girls and mothers, in fact they are designed for none of them!

It is claimed that water is reaching a whole lot of schools and anganwadis. What would you say about water quality or the manner in which it reaches the schools?

There are a lot of issues around getting water. In most cases the direct source of water itself is not there or if it is there, it is often dysfunctional.

The quality of water is supposed to be tested by the PHED (Public Health Engineering Department) at every anganwadi. But, invariably, when we asked for the report, the schools and the anganwadis said they had never seen a report from the PHED about the quality of the water they were drinking. And when we asked the PHED about it, we never found that report anywhere. Somebody must have conducted the test for sure, but we could never see it. That’s our finding.

So, in Dungarpur and Barmer, two districts in Rajasthan where we could not get PHED reports, we decided to conduct tests ourselves. Fortunately, there was some old data prior to 2014 which was available on the website of the Central Groundwater Board and some other sources about the quality of water in every gram panchayat. So some of our team members dug up that data and they discovered high levels of fluoride and chloride.

We conducted tests ourselves and involved the school functionaries, children and their science teachers. We also invited some of the people from the local village community.

Our tests showed alarming levels of fluoride. We then drew samples and asked the PHED to conduct tests in its laboratory. As per the results, all the parameters matched our findings, except for fluoride. The fluoride level was shown by the PHED as normal when, in fact, it was very high. The ground evidence of this was showing up clearly in the deformed bones and teeth of children in these areas. How can we allow this?

When it comes to the quality of food, are we faced roughly with the same kind of problem?

There is more than one model under which the anganwadi provides the supplementary nutrition. One is where there is a centralized kitchen somewhere, perhaps run by a Self-Help Group (SHG) or some central entities who are making the food and then supplying it, perhaps at the village level, the cluster level or even at city level. So it is not really being cooked within the anganwadi.

Anther model is when food is cooked at the anganwadi. In that case, funds are provided to the anganwadi worker to procure the raw materials. Some food is provided by the department through the Food Corporation of India (FCI), for instance, oil and cereals. But the anganwadi worker has to procure vegetables and the like on her own. In some cases, they are doing a very good job. I’ve tasted the food myself, sitting with them. It was very well cooked and very well served.

But, in many cases, there’s a numbers game. They would show a figure on the register and say this is the number of children who are enrolled (and present). But actually those children do not ever come to the anganwadi because nobody actually invites them there. Meals are being prepared only on paper, not in reality.

So the ingredients for the meals are all procured and then sold. The anganwadi worker gets part of that money and the rest goes up as part of that corruption process I mentioned.

Another kind of food distribution is pre-packed foodstuff meant for distribution to malnourished and undernourished children in the anganwadis. These orders are bagged either by SHGs or by some central agency and provided to the anganwadi centres.

I don’t think there is much pilferage happening in this model. I haven’t gone into the nitty-gritty of how pre-packed food is procured. I have seen some of the packing units in rural areas by SHGs and they were quite meticulous.

Comments

-

Jyotsna Lall - Aug. 1, 2022, 11:47 a.m.

I agree with Kabir Vajpeyi that we have not understood the value of child development - he may recall the Nizamuddin project where he helped us transform the MCD school. The ICDS is one of the oldest programmes that we have and looks at several aspects of child development - if only it were implemented in letter and spirit. For instance, one problem that we have constantly faced in Nizamuddin is that aanganwadis in urban areas receive have such limited space and the rent that the government offers, even after the increase is just not enough to rent a dignified space. The option of having the aanganwadi in the primary school space is often not implementable for a variety of reasons. It is well established that the brain develops to the maximum in the first 5 years of life - we really dont need further research on the importance of ECCD - we just need to put our heads down and do it.