Pradip Krishen: 'You have to grow trees that belong to Delhi's ecosystem'

'Delhi's Central Ridge could be a beautiful urban forest'

Civil Society News, New Delhi

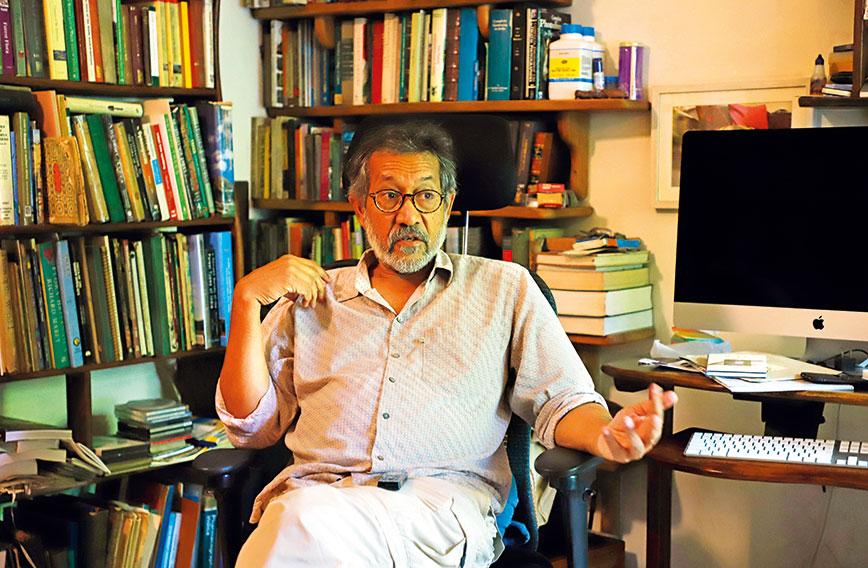

Pradip Krishen is a home-grown expert on trees. Insightful and sensitive to cultural influences, Krishen breathes life into botanical knowledge. His popular book, Trees of Delhi, is perhaps the only one of its kind on green cover in an Indian city.

A filmmaker, Krishen, now 70, began researching trees when he hit a lean patch in filmmaking. Literally, he saw from the window of his beautiful house in Chanakyapuri a tree which had always been there but whose name he didn’t know.

From then to now has been a memorable journey, which has taken Krishen all over India and across continents. Most recently, he has been greening the desert in Jodhpur and Jaipur by helping nature restore itself.

Civil Society spent a morning with Krishen in his tightly packed study for some tree talk over coffee and tea. It was a long conversation and what appears below is mostly on Delhi where citizens’ concerns over losing their trees have been growing as in Mumbai and other cities.

People are becoming increasingly concerned about trees in their cities. Delhi, in comparison to, say, Mumbai or Chennai, is still quite green. What is your impression today of Delhi’s current green cover?

Lutyens’ Delhi is green, unusually green, shall we say. Some of these trees are going to start failing because as our water table drops further, trees are going to start struggling.

The rest of Delhi isn’t quite so green. Look at the Central Ridge. It is 900 hectares, a huge chunk of territory. Almost 96 to 97 percent of it is overrun by vilayati kikar (Prosopis juliflora), an exotic, invasive species introduced by the British.

This happened due to an ecological misunderstanding or naiveté. The first eight species that were planted on the ridge were not native to rocky, thin-soiled areas. They were the wrong species. So the minute they stopped being watered, they died.

If you look at Delhi from a satellite or an aeroplane, the Ridge will look green. But it is a degraded forest.

Which species would you replace on the Ridge?

The species that you would get in a dry, deciduous forest in Delhi. There are some 28 such species on the Ridge. When I take people for a walk to the Ridge, there is a particular place, for reasons that I don’t fully understand, where vilayati kikar stops growing. That creates an opportunity for

native species to exist. It’s not as though those indigenous species were planted there. They grew there on their own.

So you’ll get amaltas, a species you get in a dry, deciduous forest. You will also get bistendu, a very beautiful smallish tree that has been planted ornamentally on Vijay Chowk where it is trimmed into these large bushes, maybe seven to eight feet high. It is the only native species that has been used in Lutyens’ Delhi. You also have the hingot tree. It sends out suckers and new plants emerge. Once hingot establishes itself, the chudail or Indian elm takes root. You get Ehretia laevis or the chamrod.

I have counted 28 species that you could expect on a rocky, ridge-like area. You have to adjust tree species according to the substrates you have.

According to the ecological zone.

According to the soil and availability of water, yes.

Sunder Nursery had done something similar.

I joined them for a year and a half in 2009 or 2010. They asked me to help create an arboretum. In my book, Trees of Delhi, I have said that you can divide Delhi into four and a half micro-habitats, which correspond almost exactly to what the Mughals might have done in Delhi. The Mughal state had an interest in assessing the quality of land and its productivity, and levied land revenue accordingly.

So if you owned land in Malcha village, for example, where the soil is rocky and ridge-like, no revenue was assessed at all. It was regarded as gair mumkin zameen.

The bangar area, on the other hand, which had rich soil and water close to the surface, was regarded as land with the highest productivity. The bangar was the old floodplain of the Yamuna which was subject to periodic flooding. Then there was the khadar, the riverine area between the banks of the river which had its own ecology. The Ridge was called the pahadi or kohi area. Finally, you had dabar which was the salt-affected area, primarily the Najafgarh jheel and its surrounding area.

These four are actually very good sub-divisions of Delhi’s ecological habitats. Each of them still has a few trees with the resilience to grow in that area.

I think 900 hectares of the Central Ridge has the potential to become one of the most beautiful natural forests that any capital city has in the world. It will take a lot of money, effort and design sense along with ecological familiarity and knowledge. I don’t think all those factors exist in any agency at the moment. Certainly not in the forest department.

Unfortunately, there has already been an attempt by Dr C.R. Babu and the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) to start something on the Ridge. I feel very sad about it because Dr Babu’s work (as head of the Centre for Environmental Management of Degraded Ecosystems) with the biodiversity parks that I’ve seen does not inspire confidence. It is not aesthetic. He knows his species well but does not plant them in a manner that simulates a natural dry forest.

For the DDA and Dr Babu to now redo the Ridge at this stage, given what we know about the way they work, think and design, is to prick that bubble of hope of the Ridge becoming a beautiful place.

But the Ridge could become a showpiece for Delhi.

There are a lot of models of what the Delhi Ridge could be like. When I first discovered Mangar Bani in 2002-03, I was completely thrilled because right here at Delhi’s doorstep was a template for what the Ridge could be like. Utterly beautiful and sustainable.

It is a sacred forest because the Gujjars who live in Mangar Bani and two adjoining villages consecrated this forest in the memory of a baba who was a holy man for them. They let it be known that whosoever breaks a twig in that forest, great harm would come to him and his family. They were the only people who lived there. Those villages are entirely Gujjar. They are pastoralists, who own cattle, goats and buffalos. When the chor becomes the kotwal, it is very effective.

Mangar Bani is under enormous threat?

It is but it is still worth a visit and it is still amazing.

What about indigenous grasses in Delhi? There has been renewed interest in grasslands in recent years.

For me, the big learning about grasslands happened in the desert. In 2006 I was given a 70-hectare plot of rocky land next to Mehrangarh Fort and asked if I could revive it. I’ve been doing that since then. We travelled a lot in the desert looking for seeds of plants that are adapted to grow among rock.

We found grasslands extremely productive, beautiful and important. Not just for themselves, but also for all the creatures they support.

In Delhi, there are no habitats left that could be grasslands. They are more like thorn forests. The words ‘thorn forest’ have a slightly pejorative sense, but I don’t mean it like that at all. I think originally, Delhi would have had a mosaic of habitats among which there would have been grasslands but there are none left, or none that I have seen. But grasses, as components of ecosystems, are very important.

Jodhpur, which is much drier and rockier than Delhi, has a volcanic substrate where I work. The rock is called rhyolite, harder than quartzite. There is no soil there except at the bottom of valleys and in the cracks between rocks.

We have 72 species of grasses there that are native to the rocky desert and lithophytes. They play a very important role and are visually very attractive and an important component of the landscape.

People talk about growing trees. But there seems to be little awareness of indigenous species.

If you ask people about the trees they would like

to have in their gardens, they will either say flowering trees or evergreen trees. We need to factor in Delhi’s climate where you have a monsoon that normally ends in September and then no rain till July the next year.

Four or five months after the monsoon, trees begin to drop their leaves as a way of adapting to drought. That act, of dropping leaves and becoming dormant, is what characterises a dry, deciduous forest everywhere.

The British didn’t understand when they were planting trees in Delhi that species must be suited to the ecological conditions of the city. It is almost a requirement that trees be deciduous, that they drop their leaves in the dry season.

The minute you talk about evergreen trees you are talking about trees that don’t belong to this ecosystem. You are talking about trees that are thirsty. And thirsty trees in Delhi’s ecosystem are unsustainable.

For me, the biggest problem that faces Delhi now and in the future is the scarcity of water. The CPWD carved out the Buddha Jayanti Park from the Ridge. They planted the same species as in the Lodhi Gardens, assuming that since they were growing there, they would grow on the Ridge. Then they realised that their trees were dying. They needed water every day. So they brought a pipeline right up to the Ridge and now they’re watering it every day using copious amounts

of water.

You grow the wrong kind of trees and then use water in a stupid profligate way.

I mean, lawns are some of the worst things to happen. Sunder Nursery has repeated that silly mistake of having vast lawns. Lawns are so inappropriate to Delhi’s climate and ecology.

What we need is a much better understanding of what is endemic to Delhi. What works for Delhi?

Absolutely. All the work I’ve been doing in Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh or Gujarat is about creating a landscape that is totally sustainable. Jodhpur is a desert, right? We don’t water anything. We don’t give any nutrients to any plant. If we see a plant dying, we say, “Look, you’re the wrong plant in the wrong place and you need to be replaced with a plant that will survive here without any aid.” And that is the way to treat large landscapes like the Ridge, not to take a pipeline all the way there and plant the wrong kinds of species.

How can it happen here?

Just by ideas spreading, really. I think the work that the Aravali Biodiversity Park does in Gurgaon is a huge catalyst. On the other hand, to my horror, I saw a pit, a water sprinkler, exotic orchids and ferns growing in Professor Babu’s biodiversity park in Vasant Kunj. And this place is touted as being all about natural flora. Is he ashamed of our native flora? That attitude has to change.

The ecological work we have done in Rajasthan, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh are, in a way, models. People come away, saying, “We never knew that you could actually achieve this.” This will spread. There are four or five people doing similar work in rainforests, dry areas of Tamil Nadu, in Auroville, and in the Northeast. It is a small movement but hopefully it will spread.

What about Delhi’s government agencies?

I once did a presentation at the request of Hardeep Puri. The CPWD was there, so was the NDMC, the Cantonment board and the DDA. They all wanted solutions. They said: “We have these kachnar trees, what do we do with them?”

I made three or four proposals. I told them, set up a large nursery for native plants in Delhi that all of you can dip your beaks into. Nothing happened.

The Urban Arts Commission did ask me if I had any suggestions for Delhi’s gardens. I had one. You need to budget for open spaces, I told them. Otherwise they will all disappear if you go on planting more and more trees every year. They said it’s a good idea but nothing has happened.

So you need a movement to promote indigenous trees?

After Trees of Delhi, my next book was about trees that belonged to the dry, deciduous forests of central India. One of the most telling statistics is how many native species we have in this country.

According to one of the Kew Institutes, it’s roughly 2,400. Now compare this with the UK which has 37. England has 11. The whole of Europe has anything between 1,200 and 1,500. The US has 1,000. Germany has 50. China and Indonesia are ahead of us, so is the Amazon rainforest. Lots of Middle American countries have more than us.

But India has an incredible wealth of trees. Do you know how many we actually use in our parks and gardens? It’s something in the range of 60 to 70 trees out of 2,400.

That is a terrible statement about us as a civilisation and the extent to which we are curious or even just open about working with our own flora and fauna.

One of the reasons I did that book was because I wanted more people to start planting trees that they hadn’t heard of. There are at least 20 species in there that are obvious candidates for horticulture, in gardens or in parks. They have never been tried, only because people haven’t been curious.

Nurseries everywhere stock the same thing and then say there’s no demand so what is the point in keeping other species? So when people go to nurseries asking for native species they are told that they don’t keep them because of the lack of demand.

People don’t plant them because they can’t get them and nurseries don’t raise them because people don’t ask for them. It’s a vicious cycle. In the last year and a half there are people who have started modest attempts to grow native plants and at least five to six other people are beginning to mull the idea that if they get a nice plot of land, they’ll plant native species. So I think the moment has come.