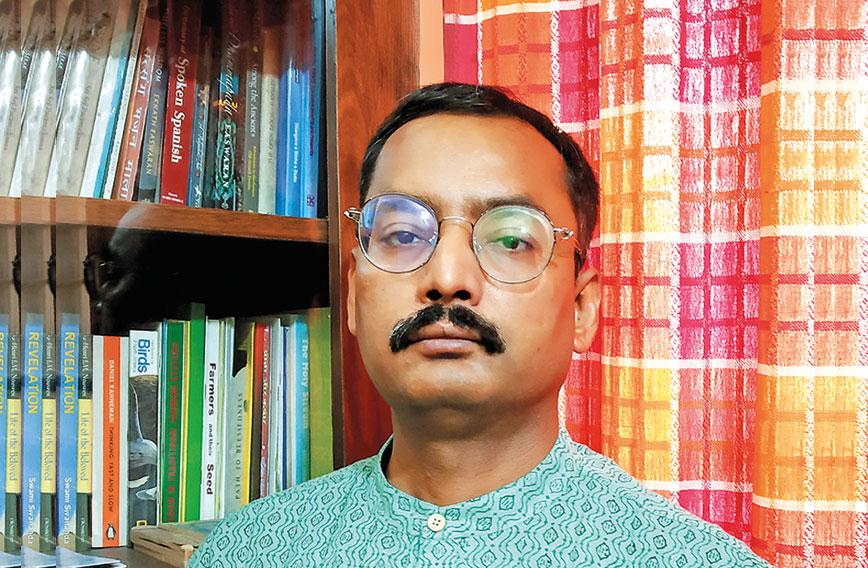

Venkatesh Dutta: ‘River cleaning is not river restoration’

Venkatesh Dutta: ‘Every river must get recognition’

Civil Society News, Gurugram

INDIA’s once-splendid rivers have long been in decline. Traditionally, rivers were managed as part of larger water systems. Ponds, tanks, streams and smaller rivers worked seamlessly to retain water. Present-day governance doesn’t know to envision such harmony.

As a result, rivers like the Yamuna dry up in summer. In Lucknow, the Gomti is practically a dead river. When the river does have water, it is polluted and smelly. The focus of most governments is on cleaning rivers by spending copious funds on Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs) and long pipelines. In Lucknow, a riverfront was built to pretty up the view of the half-dead Gomti. It ended up throttling the river.

“We have to see the river in its totality,” says Venkatesh Dutta, professor of environmental science at the Babasaheb Bhimrao Ambedkar University in Lucknow.

A passionate campaigner for waterbodies, Dutta undertakes field work to unravel ecosystems to which rivers belong. For instance, he took his students on a 10-day yatra along the Gomti during which they lived with villagers and mapped river restoration plans with them.

“The best solutions are usually nature-based and don’t require concrete, metal and cement. We also don’t require unlimited funding and resources,” says 43-year-old Dutta, a staunch believer in the strength of community action.

As Waterkeeper of the Gomti, a designation conferred on him by the Waterkeeper Alliance, a global network of people fighting for clean water, Dutta is spokesperson, researcher and activist for the river and its wiry territory.

He works with government agencies, including Namami Gange, to restore rivers including much-ignored small rivers. Government officials don’t always share his zeal and there is the bane of frequent transfers to contend with.

“I have a love-hate relationship with the government. It’s not easy but we have to be vocal,” he says. Dutta has campaigned in Lucknow too with schoolchildren. ‘My river, my pride’ got children involved in cleaning up stretches of the Gomti.

He is an admirer of India’s historic tradition of building waterbodies and views the Chandela rulers who built 100 waterbodies in Bundelkhand as an inspiration. “We don’t have such vision,” he says.

Recently awarded the Neer Foundation’s Rajat ki Boonden National Water Award, Dutta is also a Fulbright Fellow and a British Chevening Scholar.

He spoke to Civil Society on why our rivers continue to languish.

Q. Why are rivers like the Yamuna and Gomti filthy and polluted? STPs have been built at considerable cost. Why has nothing changed?

Such changes are merely cosmetic. The problem is we have a short-term view of river rejuvenation. There is no long-term planning, no vision. Nobody asks how our rivers should look in 50 or perhaps in 100 years. No one is asking this question, be it in a metropolis or a small city. The river is seen as just a small stream lost in the background, not very prominent and not as part of our cultural and historical landscape or even our urban landscape. The river is seen as drainage, which is there to ease our sewers.

After the Ganga Action Plan Phase 1, the focus was on construction of STPs. We haven’t looked at the design or technical aspects of running STPs. It is a highly energy-intensive process. In a typical urban area, it is very difficult to connect everyone with the sewer system. There are squatter settlements, informal colonies, unplanned areas, rural areas…. We haven’t looked at where the energy will come from to run these STPs. I have examined many STPs. But I haven’t found a single STP which is giving you water of sufficient quality that can be released back into our rivers.

Q: That is a startling statement.

Yes. On paper it looks like we are following all norms and protocols. But rivers are still polluted especially in urban stretches and from the outlets of STPs to two km downstream. You can see a huge amount of foam floating on the river and the smell is so foul, you can’t even stand there. We haven’t looked at the circulation of water. Water should be used, reused and returned to nature. We must understand the sanctity of waterbodies, their carrying capacity and the entire fluvial dynamics of water systems. They are like living entities.

To what extent can the river rejuvenate or heal herself? This we have not examined. We are good at the science of extraction. But we are really bad at the science of restoration. We haven’t invested in restorative science or restorative principles. You hardly come across scientists working on river restoration using nature-based principles.

Everyone loves cement and concretized riverfront development. You can take a selfie by the river but you can’t hold its water in your hands because it is so dirty. This is happening everywhere whether it’s the Yamuna or the Gomti, the Hindon, the Kali or the Krishni river.

We have so many regulatory bodies — the Central Pollution Control Board, the State Pollution Control Boards, municipal authorities, Namami Gange…. But can you show me any stretch of a river which got healed due to STPs? We have built so many STPs for rivers like the Yamuna and Ganga in Kanpur, Allahabad.

But smaller rivers are not on anyone’s radar. A river is a river whether it is a small stream or a large channel. Every river must get recognition. Every river must get due importance. They are part of our cultural history, its tapestry. But due to lack of sound ecological principles there is heavy emphasis on the STPs. River cleaning is not river restoration.

Q: What exactly do you have in mind when you say river restoration? You also went on a Gomti yatra. What did you find?

I’ll make it very simple. Two things are required for the river. First, the river must flow. And second, the river must flood. So if you stop the pathway of the river, you are killing the river.

The immediate river banks or the flooding pathway of the river, its fluvial corridor or terrace have to be protected. It is part of the river. We think the river is merely the channel through which it passes. We don’t consider the lateral connectivity of the river with wetlands or its vertical connectivity with groundwater. We have to see the river in its totality.

During my 10-day yatra along the Gomti, I found that wherever the river was protected by a vegetative corridor, a forest on both sides, even sandbanks or grasslands, it was in good health. Wherever there was space for the river to spread sediments, it was in good health. The river’s relationship with the local habitation must be maintained and not alienated by a concrete project which makes it very elitist.

A river can’t be called an urban river. Its catchment can be urban. Or its watershed could be urbanized. It should not be fragmented, over-allocated, or diverted through canals, dams or barrages. Whenever there is need for water, natural designs and principles should be given first priority. We also found the Gomti connected with its old paleo-channels, its lakes and waterbodies, ponds, smaller streams or its tributaries which fed its main channels and gave it fresh water.

Q: You are saying the flow of the river depends on its surrounding habitat?

The habitat is very important. The Gomti is a groundwater-fed river. Rivers like the Ganga, the Yamuna, or the Gandak and Bagmati coming from Tibet or Nepal, are snow-fed. But even those get groundwater in huge quantities during the lean seasons. The snow melt quantity could range from 15 to 60 percent only. The rest is groundwater supplied by base flows through the river’s channels because the water table is high and keeps contributing to its main flow.

The Gomti gets groundwater even during the lean season. During the monsoon it gets rainwater through its tributaries and connective waterbodies. Good rain is confined to only 18 to 20 days. Nine to ten months of the year, the flow is contributed by groundwater. If you lose the groundwater, you lose the river. Somehow that connectivity has been lost.

But this was known to our ancestors. They built waterbodies. The idea was to make these streams perennial. If you could hold large amounts of water through surface impoundments, like ponds, the recharge would contribute to the flow of the river system. But today we are losing those historical waterbodies. We are converting them into built-up areas in Lucknow, Kanpur and Allahabad, or most of the upcoming towns. Land revenue departments are not serious about protecting them.

Q: Those waterbodies should be protected as a matter of policy?

There is no dearth of policies. Seriousness is lacking in the lower levels of governance. You might have a beautiful policy document and it really looks like you are going bottom up. But the person responsible for its implementation will be transferred after a few months or years. So his focus is on short-term goals. He muddles along and this is the way it goes from one person to the next.

Secondly, there is conflict between the land revenue department, the irrigation department and other local bodies like the municipalities. When you ask who owns the pond or the waterbody, you won’t find an easy answer. Their area is shrinking even in revenue records.

The Gomti passes through 16 or 17 districts. Since 1976 — when I first made a land use map (of such waterbodies) — to 2021, using satellite pictures, we have lost almost 70 percent of waterbodies in the catchment of the Gomti. The land revenue department, which has the database of waterbodies, doesn’t seem serious about looking after these areas. Anyone can encroach, fill up the waterbody or build an apartment block. If anyone complains, he gets threatened. There is no security for the whistleblower. There are no groups which complain, just one or two isolated persons.

Q: You have mooted the idea of water sanctuaries. Can you explain that?

We have wildlife sanctuaries, national forests and protected areas. Waterbodies have beautiful landscapes with turtles, otters, frogs, and birds surviving in those isolated patches. Such landscapes should be declared as water sanctuaries. Nobody should be able to change their land use. Secondly, you could store rainwater in those areas and you would have a year-round supply of fresh water. Nature has designed these areas as natural storehouses of water.

The origin of the river — whether small or big — must be declared a water sanctuary, an eco-fragile zone. It should be demarcated and the river’s fluvial terrace on both sides must be protected just like the railways protect their land on both sides with pillars. The river should be zoned and nobody should be able to change land use. Water sanctuaries are the need of the hour. They can protect you from extremes of climate whether it is flooding or drought. Look at the IPCC [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] sixth assessment report. The weather is so unpredictable.

Q: Have you identified such stretches along the Gomti river?

We did and we submitted our report to the government way back in 2011. We identified 25 streams or tributaries which contribute to the flow of the Gomti. They all originate from a small forest patch or a wetland. These are critical landscapes. They are being threatened by intensive farming, or being levelled up. The very origin of the Sai river, a tributary of the Gomti, is threatened today by a highway which cuts the Sai into two parts. This year that area is almost dry. If you don’t protect the origin of the river, how will you ensure nirmal dhara?

The Sai has around 50-odd tributaries which contribute to it and it then is a tributary of the Gomti. UP alone has more than 1,000 smaller rivers. And there are thousands of kilometres of smaller channels. It’s very disheartening to note that these rivers have not been scientifically mapped. If you examine older satellite maps you will find many channels braiding, meandering or changing their course. These areas should be mapped and protected and not used even for farming. When you start farming you lose the river banks. There is a tendency to encroach. The edge of the farm and the terrace of the river intermingle and there is so much threat to the eco-zone — the transition zone from the wet ecosystem to the dry eco-zone, from a running river to a dry landscape, which is a refuge for turtles, birds, frogs and all sorts of diversity. A river is not mere water. It includes the biodiversity which flourishes in and around it.

Q: Would reviving waterbodies within the city, creating a wetland ecosystem and flowing in treated sewage water help improve groundwater levels?

Cities should have a decentralized system of water management. Water should be used and returned to nature at the colony or zonal level. The water should be treated so that it is of sufficiently good quality to be returned to a wetland or a pond. If you compromise with water quality you lose your groundwater quality and then there is no way to treat it. There are examples of bioremediation with aquatic plants. It’s a good approach but the quality of water is very important. It must conform to regulatory standards.

Q: But STPs are not the solution, you said.

I was talking about the large STPs. STPs should be decentralized and small. My thumb rule is: the STP should not be more than 10 MLD (million litres per day). More than that entails heavy costs of pumping, transport and conveyance. A lot of pipelines need to be laid. Ideally, you should divide your city into many zones and pockets and have a series of STPs. You could even make an STP below a park and use the water for gardening or irrigation or construction purposes.

We should not opt for the large STPs of 300 MLD or 100 MLD which they are putting across rivers. These are difficult to operate and costly. It costs `40 to 50 to treat 1,000 litres of wastewater. We must invest in the science of treatment and in economies of scale and for that the small STP at colony level will work better than the large STP near the river.

Large riverfronts are not for our rivers. Our rivers swell during the monsoon. They need space to spread their sediment. Rivers make their own natural riverfronts. Our rivers, particularly in the Ganga plains, meander a lot. You can build ghats. That was more rooted in our culture. Those are natural riverfronts.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!