‘Let this be the last photo-op for drought’

Civil Society News, New Delhi

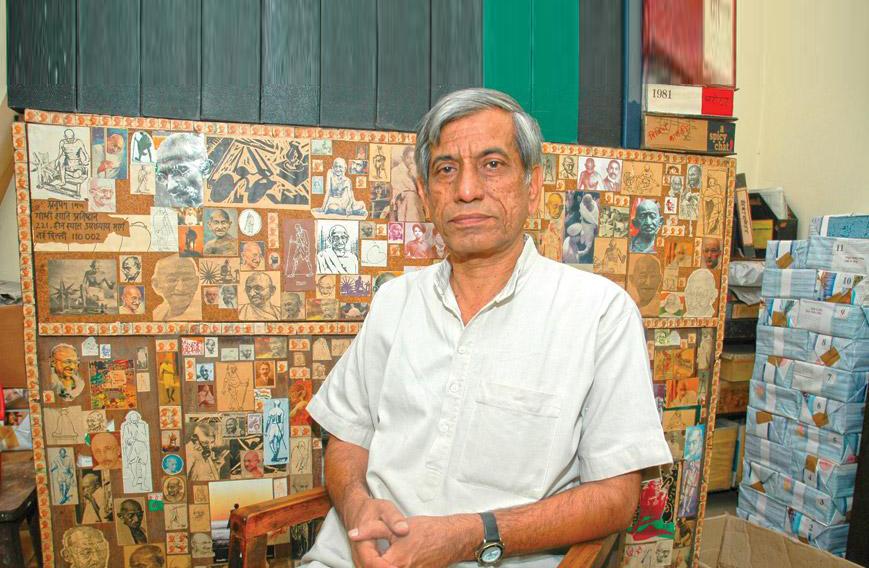

As India swings between these extremes, we spoke to Anupam Mishra, India’s most respected thinker and researcher on water, on where water policies have failed. How is it that Latur runs dry when desert communities that receive much less rain than Latur manage so well?

Mishra has spent long years studying social traditions and ancient water systems. He is the author of a revolutionary book on community water harvesting. Excerpts from an interview:

Q. We lurch from drought to flood. We have had two years of scarce rain and now we are told the monsoon will be bountiful. How should we manage our water so that we are drought-proof and flood-proof?

Drought does not come alone. It arrives after a drought of thoughts and ideas. But, sadly, we don’t see this. Nature has given us the monsoon. Even today those in positions of power think development is the panacea that will reduce our dependence on the monsoon. We have been listening to such talk since the days of the Bhakra Nangal Dam. Today, Punjab and Haryana won’t share water via a canal even though the BJP is in power at the centre and in the two states. So, thinking that this year we will have a good monsoon and all our problems will be resolved is like burying your head in sand.

The monsoon experience isn’t like going to a Mother Dairy booth. You insert one token you get a certain quantity of milk. You put in two, you get more.

It’s only when the rain falls that we know how much precipitation has taken place. That’s why since time immemorial our society, from Kashmir to Kanyakumari, designed a range of water harvesting systems to capture rain whether it was copious or scarce. This has been our tradition.

You could even say that we over-designed such systems. Perhaps, in those days, people estimated that 20 inches of rain would fall. Or maybe 35 inches. The system was designed to capture the extra 15 inches and not let rain run off into drains. So regardless of how much rain fell it was all carefully collected.

Drought would strike in those days too. There were floods as well. But the ability of an intransigent monsoon to cause devastation was blunted. People could continue to lead normal lives.

Q. Every year districts in Maharashtra are in the news for being the worst-affected by drought. Why have no lessons been learnt?

For the first time the question being raised is: should we hold IPL matches in Mumbai when the state is reeling under a drought? It is a practical question.

We have 48 stadiums where international cricket matches can be played apart from the Wankhede Stadium in Mumbai. Is there a single stadium that has a water harvesting system? Around 50,000 people can sit in a stadium. We can harvest at least 50 million to 500 million litres of water.

One minor drought in the state has bowled out the IPL. Every stadium should instal a water harvesting system so that it has surplus water which can water the pitch and supply water to Latur, if needed.

Instead, trains loaded with water are being sent to Latur. Around 12-15 years ago, water was sent by ship to coastal areas of Gujarat. So, for Vibrant Gujarat or Vibrant India — since the same leadership now rules from Delhi with the same model — just one more feat is left: to send water by air in just two hours. We could also send water by Bullet train. That would be the apex of development in India!

The monsoon has the last laugh for it bestows us rain for four months. We don’t capture it. We let the rain flow into the ocean instead.

Last night, I spoke to my friend, Chhattar Singh, in Jaisalmer. He laughed at the idea of trains loaded with water making their way to Latur.

He wanted to tell me about the last two years of rainfall in Jaisalmer. In 2014, they got 11 mm of rain and in 2015 they received 51 mm. He said in 10 villages where they had revived old water systems none suffered a scarcity of drinking water, fodder or foodgrain.

Can’t the chief ministers of Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka or Andhra take their chartered flights to these villages? And understand the strength of this wisdom?

I mean, much more rain falls in Latur than in Jaisalmer. I agree it’s not the Konkan but nature hasn’t deprived Latur of rain entirely. Maybe Latur’s population is more than Jaisalmer’s. But not a single tanker has gone to these villages in the desert that receive such scarce rain, for two years.

Q. How did the villages in Jaisalmer district become drought-proof?

Jaisalmer has an unusual geography. Thousands of years ago, nature created gypsum in stretches and patches under its sand. Gypsum halts moisture and doesn’t let it evaporate. It also prevents sweet water from mixing with saline water below.

Jaisalmer's villages have beris, kuans and talaabs with this gypsum belt. The sandy soil above blocks the sun and prevents evaporation. The sand feels warm if you touch it. But a few inches below you will find moisture blocked by the layer of gypsum.

Q. You have explained the science to us. But what about the village community’s role?

Their success and strength lie in their tradition. They know how to care for their tanks and catchments. Catchment areas are kept clean and free from garbage, cow dung and animal droppings. They take great care to ensure that their drinking water isn’t contaminated. They say with immense pride, please come and see.

And such a tradition isn’t just practised only in Jaisalmer, which is in a desert. Just five hours from Delhi is a village called Laporia which receives just 22 inches of rain. At one time three of their tanks were lying broken and it affected their lives. They decided to repair them.

That year they received 35 inches of rain, more than what they normally receive. The tanks filled to the brim. Laporia had wisely made provision for excess rain. Neighbouring villages were flooded with water. But not Laporia.

In years to come, the area would witness drought. A mere six inches or eight inches of rain would fall. Tankers, fodder and foodgrain had to be sent to villagers near Laporia.

But Laporia’s people said they didn't need any of this. They have 103 wells and every year they say, please come and see. We have enough water in our wells and we have groundwater too. There is synergy between groundwater and surface water. If surface water dries up, you can tap groundwater.

In Latur, in Marathwada, we have used technology to completely squeeze out groundwater.

In Mumbai we see a 22-metre cricket pitch but we don’t see thousands of hectares of sugarcane in Marathwada. We don’t see 125 sugar mills.

In Laporia they took a decision not to grow crops that demanded a lot of water. The community decides wisely. But if society stops making decisions, and then faces drought and then thinks it will learn from Rajasthan, it's not going to happen. You can’t copy what the villages of Rajasthan did. You have to first change the way you think.

There are places where water harvesting is just a charade. NGOs put up a board saying they have done it. All that they are doing is self-promotion. In villages in Jaisalmer they don’t put up a board announcing that they have carried out water harvesting.

Q. So it is part of their lifestyle?

It is their way of life, their culture, their tradition, and a responsibility that they pass on to their children. In Haryana and Punjab they grow paddy today. It was never their traditional crop. These states have the highest number of agricultural universities. What do those vice-chancellors do? What do they research? Why don’t they tell the government that we will not be able to undertake paddy cultivation beyond another five years because we will run out of water by then?

The traditional food of Punjab was makki ki roti and sarson ka saag. Today, it is wheat and rice and both are not of good quality. A sack of wheat will be invariably branded as wheat from Madhya Pradesh to emphasise its quality. Why don’t they write that it is from Punjab or Haryana? If you are using so much water, grow better quality wheat and rice.

Q. Many regions in India have turned water scarce. What should we do to make them water rich?

Politics in India has sunk so low it can only sink our water tables further. Politicians seem to compete with each other in reaching new lows. The politics of today cannot raise water levels. Sure, in an emergency situation you need to send water by train. Send it by plane, by all means. But ask yourself, next year how many gallons of water can be collected from the monsoon when it arrives?

Maybe the monsoon will fail. But there will be some rain. We should start with Marathwada and ensure that from 2017 these regions never ever experience such drought again. This should be the last photo-op of drought in Latur.

Q. Urbanisation is increasing at a rapid rate swallowing traditional modes of water harvesting, tanks, lakes and wells. Instead, we are depending on extracting water from rural India. Look at Dwarka in New Delhi.

Absolutely and where are the tankers drawing their water from? From villages. For how long will rural India supply urban India with water. If we can build stadiums, a Metro station and shopping malls in Dwarka, then why can’t we plan and build four large tanks? There will be rain in Dwarka and there will be flooding too. Gurgaon floods so much.

The definition of a smart city should be that the city’s management of water is very smart. Instead of depleting villages of water, cities can load up on rainwater and take what they need every day.

Whether it is Chennai or Mumbai, our cities will lurch from flood to drought. People are condemned to suffer because they are not changing their ways. The politics of this country is not changing either. And then we want water harvesting to be a success? It won’t happen. In Jaisalmer and Laporia people show immense courage.

Q. What about globally? Water harvesting is a part of modern infrastructure as well.

It is so globally. Frankfurt airport installed water-harvesting systems around 15 years ago on 10 of its runways. They did not do it out of moral compulsion. The municipality told the airport that its water needs were huge and that it would have to pay the highest cess.

Frankfurt airport did not have the money to pay. Somebody suggested rainwater harvesting. Today they don’t need to ask the municipality for water.

So why can’t Jaipur, Jodhpur, Delhi and Mumbai do it? The T-3 terminal in Delhi Airport was built in 2010. The arrival segment has been waterlogged four times since. We broke up 10 tanks to make this terminal. So can we make up the loss of 10 tanks by designing water harvesting structures? If we don’t then the monsoon will arrive and say I will drown your airport.

Chennai airport drowned for seven days. The monsoon warned its citizens, 'my strength isn’t limited to drowning bus stops, I can drown your airport too.'

Apart from Latur there is an industrial township called Dewas near Indore. Twenty years ago, they witnessed a devastating drought. Indore used to receive a pipeline of water from the Narmada. It was decided that a train ferrying water would travel to Dewas from Indore to provide relief to its citizens. The water used to be emptied from the train and with booster pumps the municipality would supply Dewas with water.

The railways said that it cost them Rs 16 lakh to carry water to Dewas every day. Who was going to pay, they inquired. Why should only the MP government pay, said its citizens. After all various industries, central government employees and so on were also beneficiaries of this water. The municipality was broke.

So it was decided to construct a pipeline from Indore to Dewas. How many cities will the Narmada supply water to? How much will you store in the Sardar Sarovar Dam? How many cities will draw water from the Ganga?

The UPA government allotted 1,100 acres for an IIT in Jodhpur. Among the team of architects shortlisted to build the new IIT was a person who asked the municipality how much water it could supply the new IIT. The municipality retorted that it could just about supply water to the citizens of Jodhpur.

For the first time, a group of architects decided to build 30 tanks for the new IIT. They decided not to grow extensive lawns. Instead they opted for agriculture to add greenery to the campus.

But what about the other IITs? Smriti Irani has started Unnat Bharat in the IITs , a programme by which the IITs are supposed to adopt villages and develop them. I was invited to speak at a meeting at IIT Delhi.

I told them, forget villages and adopt yourself. You suffer from a shortage of water. Of what use is technology and degrees when one drought in Latur overwhelms us?