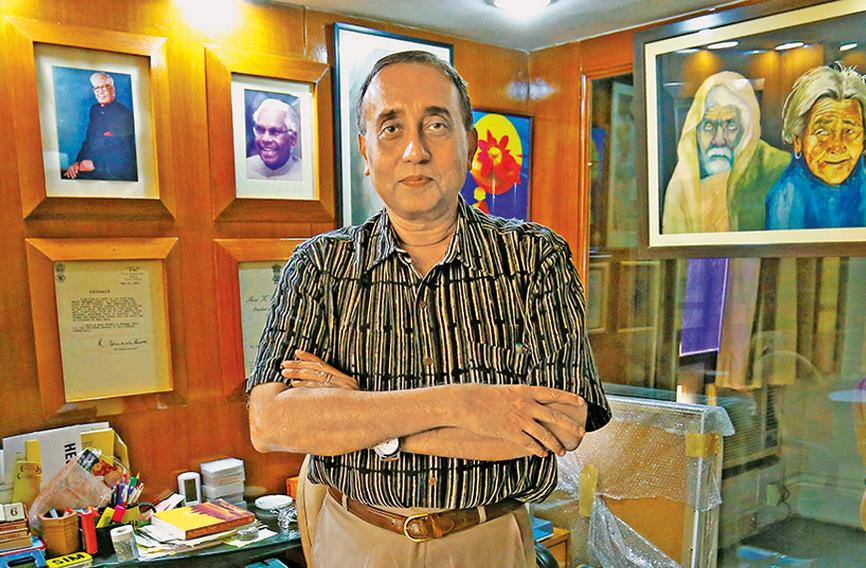

Mathew Cherian: ‘Nobody is aware of what the implications of GST are for the NGO sector’

‘NGO funding has been falling quite drastically’

Civil Society News, New Delhi

The voluntary sector in India has been under regulatory pressure for one reason or the other. Thousands of organisations have seen their licences cancelled for violating norms relating to foreign contributions. Income tax provisions, on the other hand, make it difficult to show any income at all even though it may come from bona fide social initiatives and be intended to achieve financial sustainability. Now there is GST to contend with as well since there is lack of clarity on what NGOs should be paying at the time of making transactions.

The role of NGOs as agents of development and change is well-documented. They have proved to be reliable and innovative solution providers, especially in last-mile situations. Even as the government draws on them, it makes their functioning difficult — a trend that began with the Congress-led UPA and has continued with the NDA under the BJP.

A major reason for the problem is that no clear policy governs the voluntary sector. NGOs themselves have done little by way of self-regulation so that governments can’t meddle with them.

In response to a public interest litigation (PIL), the Supreme Court in July asked the Union government to consider drafting a law to regulate NGOs. Such a law was drafted under the UPA but it didn’t see the light of day.

We spoke to Mathew Cherian, head of Voluntary Action Network India (VANI), an apex body of NGOs from across India, for his views on what could be the way forward.

It is being said that grassroots NGOs are under severe stress because of government regulations and taxation. Is this so?

We have been facing a lot of scrutiny both from the Income Tax Department and the Union Home Ministry. Slightly large NGOs have been getting scrutiny notices. There seems to be some internal circular that the moment an NGO crosses Rs 50 lakh of overall income it will come under scrutiny. In the scrutiny, the officer can ask for anything — all details, accounts, passbooks. In certain organisations, that would run into thousands of pages. So you have to take multiple copies of that and leave it with the scrutiny officer. He can demand more documentation. Most NGOs have one accountant or half an accountant so it’s very difficult for them to handle all this.

The other issue is if NGOs are doing slightly commercial work, they have to declare it else this income will be taxed in full. So NGOs selling books, magazines, artisanal craft or handicrafts all come under Section 215 of the income tax rules. Their income is treated as commercial income and not charitable money. A demand notice is sent to them.

The process is first you pay what is demanded in the notice and then you go in for appeal. If you win the appeal you can get your refund from the Income-Tax Department which is not a simple procedure and can take anywhere between two to three years.

Nobody is aware of what the implications of GST on the non-profit sector are. But one area that is going to cause concern is CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) funding. Some companies have brought CSR under their service tax provision. So non-profits getting CSR funds become vendors of services. As a result, we will also come under GST.

The company may deduct 18 percent GST and give you the chit. Then the only way you can offset that 18 percent GST is through some other GST which you can claim. But no chartered accountant is clear about the rules. So we don’t know.

Does GST apply at all to NGOs?

There are two opinions. One says if you are in the nature of providing services you may have to pay GST. So if you are providing medical services you may be classified as a service provider of medicines. If you are running educational services, and to cover costs charging a nominal Rs 50, they can classify it as a service. The quantum of charge is not important. Even for Rs 50 you will have to pay service charge.

Should the non-profit sector have been treated differently?

Yes. We should have been treated differently because the nature of the service provision is not a for-profit provision. It’s a charitable service. You can speculate whether a nominal charge of Rs 50 for remedial education or a token fee of Rs 10 for charitable health services is commercial. Many NGOs in the health sector charge a small amount for medicines.

Now this will fall under the ambit of GST and cause problems. Many organisations will not pay this GST because under each receipt you can’t say ‘GST Rs 2’. Supposing you are charging Rs 10 for a service. Instead of 18 percent you will charge Rs 2. Then they will say you charged 20 percent so you violated the 18 percent rule. You should be charging Rs 1.80 paise on a Rs 10 provision. So there are lots of things that can happen. The problem is many chartered accountants are not clear on this. There is overall confusion.

VANI doesn’t do any service for which it charges. But the sector is much larger than VANI so they might have problems with this.

There seems to be a sense that the government is deliberately doing all this to harass the voluntary sector. Is this a fact?

The scrutiny notices by the Income Tax Department seem to go to NGOs whom they want to harass. Even VANI has got one notice, by the way.

What impact is this having? Are NGOs closing down? Is the sector shrinking?

On the FCRA (Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act) front there have been huge implications. Mostly NGOs dependent on foreign funding have been struggling. There were 18 international organisations on the banned list and they have all started closing shop. Many have sent off their employees. The FCRA accounts of Henri Tiphagne’s organisation, People’s Watch, was closed and they had to lay off their employees. They have gone in for appeal.

Other smaller NGOs have closed down because they have no money to pay salaries. NGOs being supported by CORDAID (Catholic Organisation for Relief and Development Aid) or DAN Church Aid have all had to shut down or pare down their operations. In that sense, there has been a shrinking of the sector.

But because of this trouble the membership of VANI has grown. Non-profits find that we are raising our voice. They say that if tomorrow they come for us at least there will be somebody who will speak up for us.

How many NGOs have lost their FCRA licences?

About 10,000 NGOs were not given their FCRA. Some of the reasons cited were that they were not showing their full accounts. But many of these were simple clerical issues. The ministry also seems to have lost some of their submissions. VANI appealed so they allowed those NGOs to once again file online and fill in whatever was missing.

At last count about 8,000 out of 10,000 NGOs had cleared their FCRAs. At least that outcome was good and VANI’s services were found to be useful. This also led to an increase in our membership.

But the government’s online system still doesn’t work completely. When you try to upload, the system often goes on the blink. And this happens in Delhi. So you can imagine how difficult it must be for a small rural NGO in UP or Bihar to file online. Digital connectivity is so poor.

During the UPA rule there was a move to have a law for the voluntary sector. The NGO sector leaders opted for self-regulation. Do you think a proper law might have prevented this sort of situation from developing?

There was a move for self-regulation. I had chaired an accreditation committee with the Planning Commission and suggested ways to accredit. Credibility Alliance and Bright Star were also doing accreditation. We have at least 40,000 NGOs who have uploaded their accounts. It may not be a huge figure compared to the millions of NGOs around but at least so many filed.

A PIL was filed in the Supreme Court which has now established a committee to examine the issue of a law for the voluntary sector. Again we have revived the same law we had drafted during the UPA regime. Nobody in the law ministry took it up then. The issue was which ministry will deal with it. They tossed the draft law to the Ministry of Corporate Affairs, saying they have lots of experience since they have recently drafted a Company’s Bill. The ministry tossed it back to the law ministry.

What were its highlights?

It said to implement a new law, put in an accreditation system, bring transparency into the system, etc. NGOs want to be transparent and accountable but the government is not creating the systems for it. They simply publish a report each time, saying only so many NGOs have filed their returns. Under the Societies Registration Act, 1860, there is no provision that says you have to file your returns. Only Uttar Pradesh has a five-year registration law with a provision of filing your returns. So NGOs in Uttar Pradesh have been filing because it is mandatory.

NGOs working with VANI are mostly in health, education, environment and grassroots issues. Are they getting financial support from companies or the government?

Funding has been falling quite drastically. CSR money is accessed mostly by the better-off NGOs who can draw up proposals according to corporate standards. Rural NGOs don’t have access to CSR funds except if there is a factory around or a company near their place of operation. Many of them are not getting funds. The amount available to NGOs under CSR has been drastically reduced because a lot of it is being lost to Swachh Bharat and Skill India. Other ministries, too, are grabbing that money, especially from public sector companies.

Is VANI taking any measures to bring NGOs up to date on the new regulations?

Actually, VANI has done more than 15 regional workshops across the country in places like Raipur, Guwahati and Lucknow. We take chartered accountants with us to explain these rules. We have started a VANI southern hub in Chennai and an eastern hub in Kolkata. We also want to start VANI Shiksha which will explain service tax, income tax, GST and all financial regulations to NGOs.

Is VANI thinking of helping NGOs to access funding from the government or from companies?

We have been discussing this. But there are already some organisations like the Charities Aid Foundation and United Way and some so-called consulting agencies who are trying to access corporate money for non-profits. There was an article in the Mint describing them as the new set of middlemen. Actually, within VANI, there is a division of opinion on whether we should go down this route. Once we become a funding agency it will change the nature of our organisation.

Are young people keen to join or start NGOs? Is the surge to join or start non-profit building on the decline?

The surge is still continuing. BITS in Goa has started a non-profit incubator. They want to create five million NGO start-ups which can solve India’s problems. Atul Satija of Nudge Foundation has started an NGO incubator called N/Core in Bengaluru. Youngsters are coming up. New NGOs have ideas and passion but even they don’t know about the tangle of new laws.