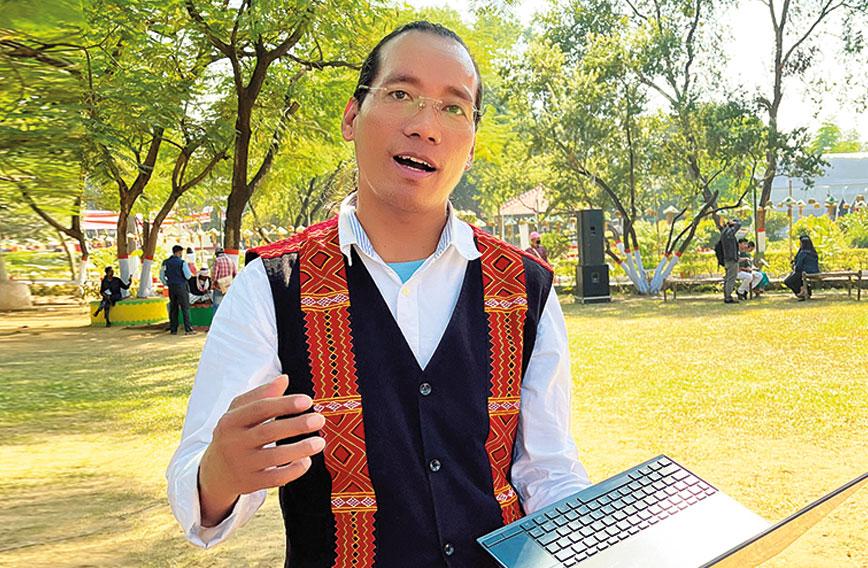

Banwang Losu: ‘We are just starting to teach the script and document folktales and folksongs which are dying’

‘It took 12 years to research and come up with a script’

Civil Society News, Jamshedpur

MUCH store is placed by early learning in the mother tongue. But what if a child is born into an oral language and if the way the community speaks varies from one set of villages to the next with intonation changing the meaning of the same word?

Such is the case with the Wancho tribals of Arunachal Pradesh. There are 56,886 of them, mainly in 67 villages in the district of Longding. But the dialects spoken by different village clusters differs so much that members of the community have to intuitively swap words to understand what is being said.

But now the Wanchos have a script of their own thanks to the innovative efforts of Banwang Losu of Kamhua Noknu village. He has brilliantly used sounds and objects native to the Wanchos to create an alphabet of 46 letters consisting of 15 vowels and 29 consonants. There are digits from zero to nine. Punctuation marks are the same as in the Roman script.

Linguistically, the Wanchos are classified into three groups: Upper Wancho (Tang group), Middle Wancho (Sang group) and Lower Wancho (Sang group). Each has its own dialect with variations in intonation completely altering the meaning of words.

The script for the first time empowers the tribe to communicate uniformly in writing. Tone markers make it possible to understand the Lower, Middle and Upper Wancho meanings of the same word. The script is entirely steeped in local culture. The letters represent human actions, animals, birds, plants, tools, tattoo marks and so forth.

|

|

|

|

| School primer: Common words in the | Wancho script with Hindi and English equivalents |

Losu says his purpose is to improve communication as well as keep the Wancho ethos alive. The script has been adopted by the government and is being taught in schools with primers as a language. On the internet it is available as a language in its own right.

It took Losu, who is now 40, all of 12 years to create the script. He started at the age of 20 when he was still in Class 11. Given an assignment to collect social and economic information from Wancho villages, he couldn’t find the Roman equivalents for the sounds of the local words and this prompted him to begin creating a separate script.

As a child Losu heard only the words used by the Upper or Tang group of Wanchos. At a very young age he was admitted to the hostel of the Inter Village School, a government-run institution, where the use of Hindi and English by teachers bewildered him and reduced him to memorizing letters and numbers.

But he persisted, finally completing his board exams and then going on to become a schoolteacher, taking classes in maths and science. The decision to invent a script also came out of his memories of his struggle to get an education in alien languages.

In 2017, Losu was given a fellowship by the Tata Steel Foundation as part of its initiative to revive and promote tribal languages and culture. As a fellow, he has been travelling to other countries and gatherings within India to talk about the script and of course the Wanchos. He leads the Wancho Literary Mission. Edited excerpts from an interview he gave Civil Society on the sidelines of Samvaad, a tribal festival in Jamshedpur:

Q: What gave you the idea of inventing a script for the Wanchos?

Actually I had no intention of developing this writing system. But when in Class 11 we started working on a socio-economic profiling of the Wanchos and I tried to put data we had collected into my mother tongue using Roman alphabets I found I couldn’t. The Roman alphabets were not adequate for capturing our sounds. Our language comes under Tibeto-Burman languages and is a tonal language. Meaning changes with the sound.

Q: Even a slight change means something completely different?

Yes, a different meaning. It was also difficult to capture that sound in another script writing system. I was not aware of phonetics, being in Class 11, and there was nobody to help me. You know, an expert like a linguist. So, it took a very long time for research because of the variations in our community — that is, Upper Wancho, Middle Wancho and Lower Wancho.

Q: And you are?

I am Upper Wancho. So, I was not very familiar with the language of the Lower and Middle Wanchos. To create the script I had to learn their language also.

Q: How many years did it take?

It took as long as 12 years to finish my research. Then I showed my research work to my friends, some seniors, those who were well educated and in government service. After seeing my work they came forward to support me.

Q: How do people from the Lower, Middle and Upper Wancho speak to one another? How can they understand one another?

The sound is different. The tone is different. But we understand. It is like you use different words for the same thing. In Hindi, for instance, when you say pahad and parvat they are synonyms. So also gagan, akash and asman. It is like that. We recognize one another’s words for the same thing. So in Upper sky is gang, in Middle it is zang, in Lower it is rang. When we speak we understand.

Q: Can you give another example?

For water, in Upper Wancho we say csi and also sung. In Middle and Lower it is ti.

Q: Now for all three there is one script?

For all three the script is the same. Only the tone marker is different.

Q: What was the turning point for you?

It was when I could not write our sounds using Roman letters. We needed some different tools to write the tone and sounds. So I was doing continuous research and collecting sounds in our language. Finally, I found 46 sounds with glottal stop. Glottal stop means to stop suddenly. Like ‘Ka’, ‘La’, ‘Na’, ‘Pa’. These sounds were not available in other scripts like those used for Hindi and English. We have 15 vowels and 29 consonants with diacritical marks to identify the tones. The long mark means Upper language, the dot Lower language. The script doesn’t vary. Only the tone does.

Q: How many letters are there in your script?

There are 44.

Q: And you came to 44 based on the sounds you are using?

Yes.

Q: How did you choose the letters?

It is all relevant to our culture, cultural items or crafts.

Q: So where do they come from? There was no script.

These designs come from tattoo marks, insects, birds, animals, crafts.

Q: It means these are all creations of yours. You have created them?

Yes, I have created them.

Q: Okay, you took the sounds and then you came up with the letters based on what was around you from tattoo marks to animals to postures and so on.

So that people understand easily.

Q: Are children being taught in the script yet?

Yes. In government schools. This is the schoolbook (he shows a primer) printed by the government of Arunachal Pradesh. This book is for the sixth, seventh and eighth standards. This is by the State Council of Education and Research and Training department of Arunachal Pradesh.

Q: Is there a problem getting teachers?

There is a huge crisis. So I approached the government to recruit teachers especially for this, but the government says it has no funds for salaries.

Q: Are you then using the regular teachers?

Yes.

Q: But they don’t know the script.

We are training them. But it is not up to the mark. Not as we wish.

Q: Of course there is a shortage of teachers, but does a child learn geography or history or mathematics in this script now?

No. We are just starting to teach the script. Folktales, folksongs which are dying — to document them.

Q: You are propagating the script which matches the way people talk and you are reviving your folktales and songs.

Yes, at first only this. It is important to revive folktales and songs otherwise they will die. Next we will translate course material in science, social science, mathematics, geography.

Q: For how long has this script been in use in schools?

It was started in 2016. At first it was in select schools. Now the government has introduced it in upper primary and middle schools for Classes 6, 7 and 8.

Q: This is an achievement. From a village in Arunachal you create this script. You’re a leader. What does your community think of it?

They are very happy.

Q: You come from a farming family.

My father and mother both are farmers. Now I’m basically a government servant. I am in a teaching job.

Q: When you went to school you knew only the Upper Wancho dialect?

Yes, at that time.

Q: What language were you studying in?

It was mainly Hindi and English, as in government schools.

Q: And you had no difficulty using Hindi and English though you only knew your Upper Wancho dialect?

It was difficult. It’s very difficult for children.

Q: What was the process of learning?

We used to learn the alphabets and numbers.

Q: Fully paid for by the government?

Yes. It was the Inter Village School in my village, Kamhua Noknu.

Q: The school was located in your village and it was serving a whole lot of other villages as well?

Yes, five villages.

Q: Your family home was in the village but you used to live in the hostel?

Yes. It was very strict at that time. We were never allowed to meet our parents except on holidays.

Q: But they never came from your village.

Not from my village.

Q: So they were teaching from scratch? You were learning Hindi and English.

And Assamese.

Q: You were saying that in Class 11 you were 20. Delayed schooling, was it?

Yes. In terms of the literacy we talk of, you know, we are still behind. I got to go to school very late.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!