‘Good advice on Joshimath ignored,’ says Ravi Chopra

Civil Society News, Gurugram

The religious town of Joshimath is sinking and making headlines. Buildings have developed cracks and people are being moved to shelters. It is not every day that a mountain reclaims a whole town, but in Joshimath’s case the signs were all in evidence. It is just that they were ignored.

Prescient votaries of careful development in the fragile ecology of the Himalayas have been cautioning against the building of wide roads and hydropowerdam projects. But both have been happening on a scale that mountains can’t cope with.

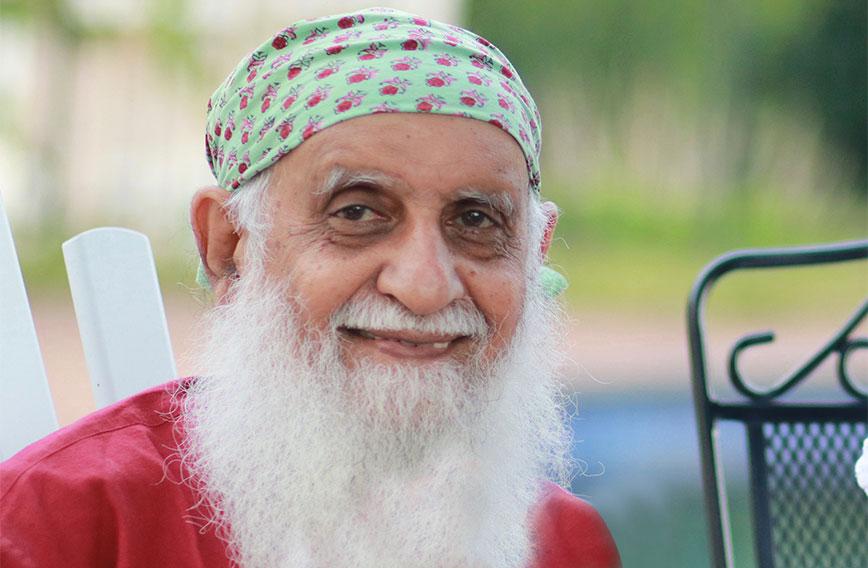

Ravi Chopra’s has been one such voice over the past 34 years.An engineer with an IIT degree, he set up the People’s Science Institute in Dehradun in1988. More recently, he was on an expert committee appointed by the Supreme Court to study the impact of hydropower dam projects in the Himalayas. He finally chose to resign from the committee in 2021 because he felt the government was impervious to scientific advice.

Civil Society spoke to Chopra, 73, in an extended interview, excerpts of which appear below:

Q: Why is Joshimath sinking? What is your assessment?

My assessment is that a number of factorsare causing Joshimath to sink. This phenomenon has a history and an immediate cause. If you look at the history, this is old landslide debris left behind by glaciers which has stabilized over centuries. The first major assault on this location begins after the 1962 war with China after which roads were built. An army cantonment was located here later, which is necessary.

In the building of roads, however, the kind of care that was needed to be taken, it appears, has not been taken. That can also be excused. In those days there was no experience of building roads in such mountainous areas. Thereafter,cracks began to develop in different parts of the town and the UP government appointed the Mishra Committee — Mishra was the divisional commissioner at that time and Bhure Lal, the famous IAS officer, was the DM.

The committee cautioned against unplanned urbanization. It cautioned against deforestation and, most importantly, it cautioned that the toe of the hills should not be disturbed because the slope above is sensitive and prone to sliding. Now this is in 1976.

The tunnel construction goes back to 2005 or so. That’s when construction of hydroprojects began. I was just reading a paper, published in 2006, which talks of the development of cracks, particularly in Ravigram in Joshimath — the area most affected now.

After the state of Uttarakhand was formed, to boost tourism, infrastructure wasenhanced, and the population of the town increased to

around 20,000-25,000. The care that mountain towns and cities require was not given. The Mishra Committee’s recommendation not to deforest was forgotten.

To make the slopes attractive to skiers in Auli, which lies above Joshimath, the slope was ‘designed’ and a ropeway was built. In 2009, I think, the first signs of a major disaster occurred— the sudden leakage of water from the hillside which is traced to the tunnel boring machine of the Tapovan-Vishnugad project that seems to have punctured an aquifer.

There are reports that several of these kinds of ingresses in aquifers have occurred. So, 700-800 millionlitres of water wasbeing discharged per second and the aquifer was discharging 60-70 million litres per day. At that time a report by two scientists from Garhwal University says:“This sudden enlarged descale watering of the strata has the potential of initiating ground subsidence in the region.”

As a member of the Expert Committee set up by the Supreme Court in 2013, we also looked at this issue of dams being built in the higher regions of the Himalayas. The Vishnuprayag hydropower project had been destroyed at that time. We came to the conclusion that this is a paraglacial zone, that there is a lot of glacial debris left behind in this zone which during heavy rain can be mobilized and brought down with devastating effect.

We said that at roughly 2,200 m elevation, dams should not be built. Later we revised it to beyond the main central thrust. That means beyond Helang in this valley, dam construction should not take place.

Of course, the government does not listen to all this.

Q: Then you have disasters?

You have the 2021 disaster. It results in a lot of debris and water coming into the tunnel. The tunnel work is then suspended. But that water is sitting there. Local residents have said that there have been blasts in the tunnel thereafter.

It can be that during that blasting some new fissures opened up. The mass of water was trying to push its way forward. And ultimately it finds a route and in finding that route it weakens the soil cover above it. That is what we saw on January 2 or 3 whenwater leakage started appearing below the Jaypee (Vidya Mandir)campus.

I should addthat the heavy release of underground water in 2009 may have also led to subsequent subsidence.

The final straw came when the Helang-Marwari bypass was to be built. The people of the town were apprehensive about the road. They thought their economy would suffer because tourists would just bypass the town.

We were not too keen on sanctioning this particular project because of the Mishra Committee’s recommendation that the toe of the hill should not be disturbed. The BRO (Border Roads Organization) was adamant about building the road.

In the course of discussions, we undertook a field visit. The BRO pointed out that their road, from Helang to Marwari, a stretch of five and a half km or so, would be constructed along a hard rock portion of the hill and not the debris portion of the hill.

So, given its importance for defence purposes, which the government put forward, we made a compromise suggestion. We said that the traffic going to Badrinath should go through Joshimath so that people’s businesses are not affected but for the returning traffic this bypass can be opened up. There are traffic jams in the town during the tourist season, so returning traffic can come via this road. In which case you don’t need a 10-metre tarred surface road. You need to cut (the hill slope) less.

So, we approved the Helang-Marwari bypass with the additional caveat that before any work starts there has to be a very thorough geological, geophysical and geotechnical analysis. Locals tell me there has been blasting for that road. This should have been avoided as far as possible.

This is the history, and the immediate cause of subsidence is dewatering of the tunnel, I suspect.

Q: Is Joshimath doomed? Can it be saved?

It is too early to say until I make a field visit and talk to senior geologists whom I can trust. I would say what appeared in October 2021 was dismissed as a localized phenomenon. Even a year later, people were thinking this is a localized phenomenon happening in one or two wards.

By December 2022, some 500 houses were in trouble. And now it appears houses through a large part of the town are damaged. The Experts Committee sent by the state said that an area of about 1.5 square km is affected. The chief secretary has informed the PMO that a strip about 350 m wide in that area has crashed. Dr Piyush Rautela, director of the Disaster Mitigation and Management Centre of Uttarakhand,says that the slide is affecting the whole town.

We have friends who live close to Auli and they are saying their houses have developed cracks. So,I suspect a large part of the town is threatened by the slide. We are fortunate that we are not in the monsoon season. We still have time to do a careful study and see how much of the town can be saved and retrieved.

Q: Isn’t there any urban planning specific to hill towns?

There isn’t. But there is a very serious need to devote deep thought to how to plan mountain cities. You look at Shimla, Mussoorie, Nainital. Buildings are precariously located. Trees are chopped down. The green cover drastically reduced. Vegetation has disappeared.

Most of these cities are unfortunately located on old debris. We have seen problems in Dharchula in the east, and in Uttarkashi district in the west. We need a completely new understanding of how to build mountain cities, based on carrying capacity studies.

Q: Do you see many more towns and villages in this region getting similarly affected? Is there going to be a cascading effect? What has been the effect of the Char Dham road building, for instance?

If you see the report of the high-powered committee, you will see a list of vulnerable zones that have been created as a result of the Char Dham Pariyojana. There are certain zones that may be described as being permanently affected. There will be landslides there. It will be difficult to stop that.

As I said, the kind of care that was needed to be taken was not taken. It was clear to many of us in the committee that the ministry had given a certain deadline and engineers were working according to that deadline. All caution was thrown to the wind.

Q: Is this entire pilgrimage route now subject to landslides, subsidence, flooding and so on?

I would say there are vulnerable zones. There are landslide zones on all the highways and government officials now recognize that. To give you an example, a little while ago, they agreed to build the last 25 km of the highway to Yamunotri on an intermediate width design. We had been arguing that the full road should be built according to that design. Now they’ve concluded that it is a very vulnerable stretch, and they will use the intermediate width design.

We did a preliminary calculation which included a few factors for the carrying capacity of Gangotri. We concluded that most likely the carrying capacity of Gangotri has already been reached or is about to be reached in the near future, in this decade.

The current road from Uttarkashi to Gangotri, about 100 km, has a tarred surface of about seven or eightmetres and traffic is moving on it. We do not think it is necessary to expand the width of that road. But the BRO and the ministry are bent on making a 10-metre road. Now to do that you will have to do substantial cutting of the mountain slopes which, at many locations on that stretch, have a very high degree of slope. The official recommendation is that more than 35/36-degree slopes should not be cut.

But on the Uttarkashi-Gangotri stretch, slopes are 50 degrees, 60 degrees and 70 degrees. But they are pushing ahead, saying this has to be done.

There are treasures on that route. If you go to the Char Dhams today I can guarantee you will get asensation when you travel on the Uttarkashi-Gangotri stretch. You will think, Yeh elakakitnasundarhai. You will get this sensation because it has been declared an eco-sensitive zone and haphazard construction has been restricted.

Beyond Uttarkashi there is the town block headquarters of Batwari where the slope is sinking just like Joshimath. The river cuts past it below and from the town the earth is sliding down.

In 2010-11, the road just sank. Several shops on the side of the road cracked. These are not new things. We know where the vulnerable zones are, but we have no plans on how to handle them.

Q: Why are people not objecting. Uttarakhand has a history of protests against ecological destruction, the Chipko movement, the Tehri Dam agitation and many more. Is Joshimath going to be a turning point?

If Joshimath can’t be a turning point phirtohhalat bahut kharabhai. Then only the Almighty can save us, though I’m not a believer in God. Because a number of warnings that have been given, have come true.

It is not as if there haven’t been protests but the construction lobby and the dam lobby are the strongest lobbies in the country. They are not stupid. They deploy their intelligence to safeguard their business. Therefore, they have learnt ways of breaking up society into people for them andagainst them.

Just like the dam lobby splits society, the government too has its scientists who are worried about their jobs, if they don’t toe the government line. I’ve seen this in the Char Dham committee. Out in the field when we were seeing landslides and disasters, the scientists would all castigate the construction companies. But when it came to writing these views down, then they would not support criticism. They always wanted to moderate their statements. So, the scientist community can be easily split.

Q: Have any dams been cancelled?

Three projects on the Bhagirathi were cancelled after Dr G.D. Agarwal’s fast. The Wildlife Institute of India had recommended that 24 projects on the Alaknanda-Bhagirathi basin be removed. The court had asked us in 2013 to review those projects. Our recommendation was that 23 out of the 24 dams should be cancelled.

We wanted to cancel all of them but one of our members, a representative of the Central Electricity Authority, refused to sign. Since much of the damage on that stretch had already been done by the Tehri Dam and the Koteshwar Dam, we agreed he could build one dambut we gave him a series of conditions. We were confident it would be hard for them to meet those conditions.

But all those 24 dams are still stuck in court. At some point in the past decade there was a meeting in the PMO where a PMO official said we will permit only seven dams to be built and no more. This was in reference to the Alaknanda- Bhagirathi basin where 70 dams were to be built.

Comments

-

Pavitra Mohan - Jan. 16, 2023, 3:34 p.m.

Among the glorious snow white mountains, the Sage pondered on nature of reality The world is real and is unreal too, The world exists and exists not, God is of form and is formless too. God is efficient cause of the world And its material cause too. Majesty of the high mountains and Calm of their snow peaks were witness To the lofty thoughts of non-duality - revealed to or by the great sage? Majestic and calm, they stayed witness to many seekers who passed by Or stayed on to reflect on what the great sage. Had pondered over and spoken with clarity. Many centuries ago, on their sacred lands. When faced with greed of the modern world, which, armed with earthshattering machines, stormed in their sacred lands; they thundered, And the sacred lands cracked, sinking down in disgust.

-

Amit Kumar Bose - Jan. 16, 2023, 8:44 a.m.

On Joshimath, I'm told that there is an overground 'development' issue, as well as an underground seismic issue for any breakdown of soil and environmental ecology to take place. Our own 'young fold' Himalayas -- our pride, our possession -- will need to 'unfold' in geological time. I think it's begun. A flattening out. Couple that with our unregulated building of reinforced concrete residential structures across states that share the fragile Himalayan ecology. All over, from Darjeeling to Dehradun, Namdapha to Nainital, have these ugly heavy steel-and-cement pillars plunging into fragile soil systems of sub-Himalayan and Himalayan India. Can't we see it? It's been happening over 50 years! No regulation, yes. But what about no concern by greedy local landholders and builders? Finally, they will learn a lesson. Thanks to Joshimath. Or will their formidable avarice overcome it?