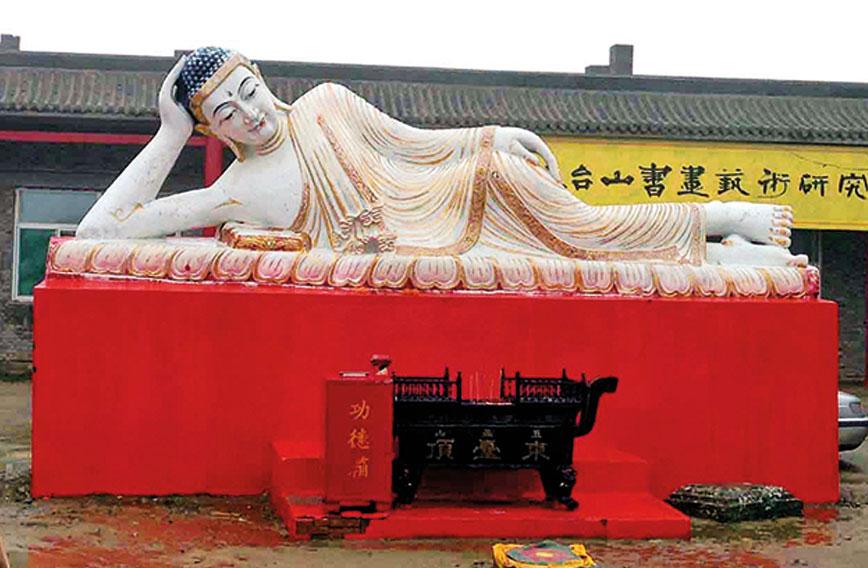

A reclining statue of Gautama Buddha

Tracking monks and pilgrims

THERE was a time when monks and wanderers travelled seamlessly from India to a swathe of territory across Central Asia and East Asia. No passport, no visa. They took with them the message of Gautama Buddha. Over the years an indelible Buddhist philosophy, art, architecture and culture took root which till date is incredibly Indian at its core.

THERE was a time when monks and wanderers travelled seamlessly from India to a swathe of territory across Central Asia and East Asia. No passport, no visa. They took with them the message of Gautama Buddha. Over the years an indelible Buddhist philosophy, art, architecture and culture took root which till date is incredibly Indian at its core.

We know that such journeys began from the time of Emperor Ashoka and ended with the destruction of Nalanda, the most revered university of those days. Travellers and pilgrims like Hiuen Tsang and Fa Hien came to India and wrote extensive travelogues. What was the impact of this intermingling of minds? Why did Buddhism spread so deep into the heart of East Asia?

Deepankar Aron, an Indian Revenue Service officer, answers some of these questions. He set off on a series of journeys along many of the routes travellers and monks trod in those years. He visited Mongolia, China, Taiwan, Korea, Japan, to explore their historic ties with India. His book, On the trail of Buddha, is startling because it reveals the extent to which those links continue to be robust, even in communist China. Many of the Buddhist sites he visits are World Heritage sites.

Aron illustrates his travelogue with eye-catching pictures so the reader gets an idea of the places he describes. His travelogue is also anecdotal and includes his meetings with local people, the bustling bazaars of Kashgar, the serenity of Japan’s gardens, the rhythmic beating of drums and chanting at the monasteries of South Korea and Taiwan.

Everywhere Aron goes Buddhism is revered and respected. He sees art, architecture, paintings inspired by the Buddha. There are Buddhist temples atop hills, rock-cut temples, temples cut into mountain sides, caves with paintings like Ajanta and Ellora, grottoes, even a hanging temple on a sheer cliff. Every country has astonishingly massive statues of Lord Buddha in different positions: standing, sitting and reclining. Or etched into high cliffs with an array of Bodhisattvas. The most spectacular one seems to be the Dafo, ‘the world’s largest rock-cut Buddha ’, in Leishan.

Aron’s book is full of revelations. Here’s one: the White Horse Monastery in Luoyang, built 2,000 years ago, is regarded as the birthplace of Buddhism in China. In AD 67, he writes, Chinese Emperor Han Mingdi dreamed of a golden angel flying in front of his palace. He asked Fu Yi, his consultant on divine matters, to interpret his dream. Fu Yi told him about Lord Buddha in the ‘west’. A caravan was sent to learn more about Lord Buddha and they returned with two Indian monks, Kasyapa Matanga and Dharmaratna. The Temple of White Horse was built for them: they had come on white horses down the Silk Route.

Aron’s book is full of revelations. Here’s one: the White Horse Monastery in Luoyang, built 2,000 years ago, is regarded as the birthplace of Buddhism in China. In AD 67, he writes, Chinese Emperor Han Mingdi dreamed of a golden angel flying in front of his palace. He asked Fu Yi, his consultant on divine matters, to interpret his dream. Fu Yi told him about Lord Buddha in the ‘west’. A caravan was sent to learn more about Lord Buddha and they returned with two Indian monks, Kasyapa Matanga and Dharmaratna. The Temple of White Horse was built for them: they had come on white horses down the Silk Route.

The two monks did remarkable work. They translated Buddhist scriptures from Sanskrit to Chinese, bringing out the Sutra of 42 Chapters, a treatise on Theravada Buddhism. Other compilations followed. Luoyang with its 1,300 Buddhist temples, became a centre of Buddhism and its many versions, spreading into Korea, Japan and southeast Asia. The two monks, interred in the temple, are deeply revered by pilgrims.

Here’s a second revelation. Another monk, Bodhidharma, known as Tamo in China, came from Kanchipuram in South India to the Shaolin Temple. He is considered the founding father of Zen Buddhism and the Shaolin martial tradition of kung fu which probably originated from kalaripayattu, Kerala’s ancient martial tradition. There are many more such stories.

But what happened to the redoubtable Hiuen Tsang or Xuanzang? He returned from Nalanda with Buddhist scriptures in Sanskrit written on leaves. He set himself up at the Wild Goose Pagoda in Xian and started a Sutra Translation Institute. He got 350 monks to translate almost 1,335 volumes of 74 Buddhist sutras, the magnum opus of Chinese Buddhist literature.

It was this immersive body of profound philosophy, collated by Indian monks and Hiuen Tsang, along with the patronage it received from royalty, that helped the spread of Buddhism. When Nalanda was razed all its manuscripts were burnt. If you want to see some of those ancient writings, travel to the Wild Goose Pagoda.

The practice of Buddhism continues to flower in South Korea, Taiwan and Japan. In China, it seems mainly the older generation continues to follow the path of Lord Buddha. There is the imprint of the Indian monk across East Asia, apparent in the use of Indian names: a lovely Deer Park in Japan and mountains named Gayasan in South Korea. Nara has as many as eight World Heritage sites devoted to Buddhism, and a 16-metre bronze statue of Buddha. The three monkeys which Gandhi often cited are actually from the temple of Toshu-gu in Japan.The best of ancient India lives on in East Asia.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!