Tracing India's art cinema

Saibal Chatterjee

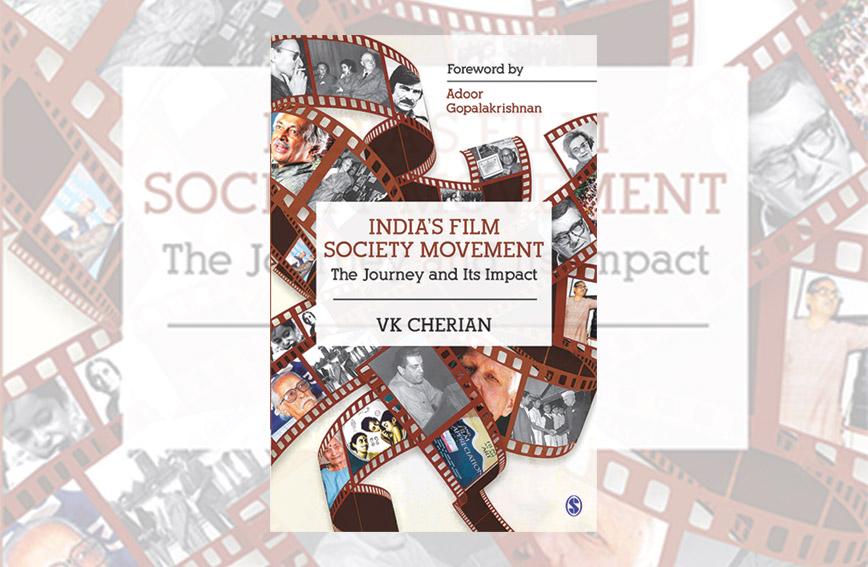

The importance of this book, authored by V.K. Cherian, a film society activist and communications professional in New Delhi, is that it is the first serious attempt to write a history of the film society movement — a movement that helped alter the landscape of Indian cinema by fostering an appreciation of the works of filmmakers from all over the world and consequently understanding the aesthetics of the medium.

India’s Film Society Movement: The Journey and its Impact is also significant due to the granular manner in which it goes beyond just history and paints a vivid narrative peopled with passionate individuals who saw cinema essentially as an art form, as a way of developing new ways of seeing and grasping, and as a means to understand societies and nations. Cherian does this on the strength of meticulous research and numerous trips to different parts of the country, not the least his hometown, Thiruvananthapuram, and interactions with the men and women who were at the forefront of this post-Independence cultural movement.

The book opens with a foreword by Adoor Gopalakrishnan, who pioneered the film society movement in Kerala (which now has a massive cluster of film societies), and a note by Shyam Benegal, who was instrumental in setting up a short-lived film society in Hyderabad in the wake of the release of Satyajit Ray’s epochal Pather Panchali. It then places the early initiatives in this domain in the global context and traces the eventual setting up of the Calcutta Film Society (CFS) on 5 October, 1947, at a meeting in Chidananda Dasgupta’s attic of 19 founding members led by Ray.

The author quotes Dasgupta thus to underline the purpose of CFS: “It was a period of discovery. Suddenly, we saw what cinema could mean and how different it could be from what went under its name.”

CFS was indeed a turning point. From there on, there was no looking back as the number and geographical spread of film societies increased steadily.

In his illuminating foreword to the book, Gopalakrishnan writes: “At a time when the cinemas of Europe and the East were inaccessible to cinephiles of our subcontinent, film societies provided us with the special privilege of watching, relishing, debating and writing about the very best of world cinema.”

The process of enrichment, hastened by the founding of film societies in many cities and towns of India and the eventual advent of the Federation of Film Societies of India (FFSI) in the late 1950s, led directly to the emergence of a new kind of cinema that went beyond the purpose of providing sheer entertainment to the masses.

Films cast in the popular song-dance-and-melodrama mould have continued to hold sway over India, but the film society movement as a force (that has galvanised makers and lovers of alternative cinema) has never lost relevance. Cherian brings that out, falling back on the reminiscences of the leading lights of the movement as well as on his own experiences as a film society activist forever committed to seeking out films and filmmakers not easily available in this country rather than being excited at the fads of the moment.

That spirit is central to his book as it traces, step by step, the progress of the film society movement. As film societies, with the active participation of enlightened personalities as well as governmental and institutional support, took root in Calcutta, Delhi, Bombay, Madras, Lucknow, Patna, Bhopal, Agra and Faizabad (yes, even Faizabad), it became clear that they were here to stay.

Cherian identifies British film scholar Marie Seton’s eventful lecture tour of 1955-56 and the global critical success of Pather Panchali (1955) as the catalysts for various film societies coming under the umbrella of a federation and lending the movement sustained coherence. The illustrated lecture tour took Seton, who later wrote a biography of Ray, to Allahabad, Benaras, Gaya and Ahmedabad, besides Delhi, Bombay, Calcutta, Madras and Bangalore.

Vijaya Mulay, a key member of the federation for decades, remembers the historic day of the formation of FFSI (13 December 1959) thus: “I went to Teen Murti House and told Ms (Indira) Gandhi that she must become the vice-president of FFSI. She asked me who the president was and I told her it was Satyajit Ray. She readily agreed to be the VP and remained in the post till she became the minister for information and broadcasting in Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri’s Cabinet in 1964.”

Would any contemporary politician, no matter how insignificant, deign to work under a filmmaker in any federation? Politics has changed and so has cinema. Yet, all these decades on, there is no reason to believe that even though the world has been shrunk by technology and the means of delivery has changed dramatically with the likes of Netflix and Amazon the film societies have outlived their utility. They haven’t: that is the unequivocal takeaway from Cherian’s book.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!