The state is a hub of research efforts on hornbills and plant ecology

The deep forest and its many treasures in Arunachal

Civil Society Reviews

IT was the search for plants that hornbills feed on which brought Navendu Page, a botanist and wildlife expert, to the Pakke Tiger Reserve in Arunachal Pradesh. Dr Aparajita Datta, a senior scientist with the Nature Conservation Foundation, was studying hornbills with her student, and needed a helping hand.

“Hornbills are predominantly fruit-eating birds. Almost 60 to 70 percent of their diet consists of fruits. The Northeast, and Pakke in particular, has three or four species of hornbills. Although Aparajita had identified many plants the birds feed on, they never had a botanist go there and formally identify all of them,” explains Page.

With its misty forests, gorges, rivers and wildlife, Arunachal is a paradise for plants. A mosaic of indigenous tribes adds to its allure as a destination for travellers and tourists. Located at the junction of Myanmar and China, the state has the largest forest cover in India after Madhya Pradesh.

“One of the first forests I explored in detail was in Arunachal. And I was absolutely mesmerized, blown away, by the huge diversity of plants the state has. It is by far one of the most biodiverse states in our country. It’s also one of the least explored,” says Page.

|

| Aparajita Datta |

As Datta and Page began their floristic explorations, they realized that the state’s plant life had barely been documented. For the lay reader, there was nothing. That’s how the idea of doing a book took root. Their third co-author, Bibidishananda Basu, also of the Nature Conservation Foundation, joined as an intern and proved himself so useful he became a co-author.

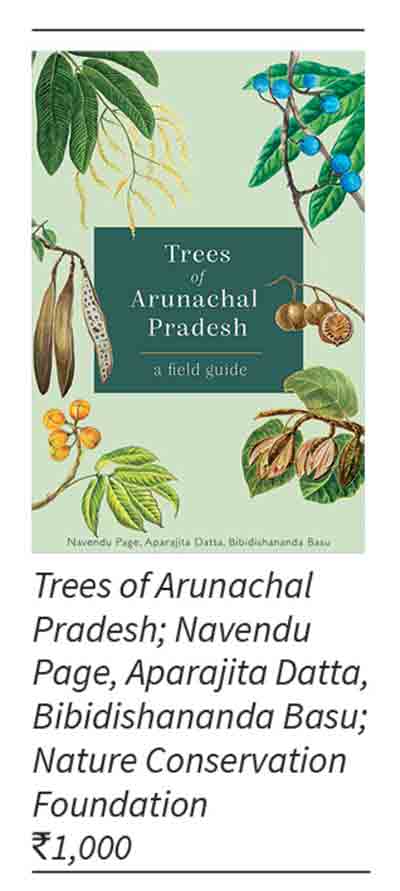

The explorations of the three intrepid field biologists into Arunachal’s forest ecology, spanning two decades, is contained in this book, Trees of Arunachal Pradesh. Attractively designed, it has 1,500 pictures of 241 species of trees, shrubs and climbers mapped by them. Also included are flowering and fruiting times, who eats the fruit and how seeds are dispersed, explains Datta.

The book is easy to use with ‘keys’ to help the reader navigate. “These ‘keys’ are based on easily observable characters such as leaves, flowers and fruits. They provide pointers to compare similar-looking species, helping to get past the lookalikes and identify the plant of interest quickly and accurately,” explains Page.

To ensure local people can use the book, the authors have included names of 18 different

|

| Bibidishananda Basu |

languages of the northeastern states, including Nyishi, Idu Mishimi, Adi, Apatami and Lisur from Arunachal. There are names in Bengali and Nepali for some species as well.

Why is Arunachal’s ecology so unique? Because it has a large family of plants from Southeast Asia, China, Myanmar as well as central India, all living in happy unison.

“It’s unique, like the rest of the Northeast, in terms of its species composition and huge number of species,” says Datta. “The region is contiguous with Southeast Asia which is part of the Indo-Burma floristic region. So, in terms of species composition, the Northeast is very different from the rest of the country.”

Arunachal also has a wide gradient in elevation, meaning you have forests that range from as low as 100 m to 3,000-4,000 m. So you get to see distinct vegetation types. And with that comes a great diversity of plants.

|

| Navendu Page |

The book is not the last word on Arunachal’s plant ecology. There are approximately, say Datta and Page, around 6,000 to 7,000 flowering plants and taxonomists are constantly discovering new species. The book covers woody plant species in the tropical lower elevation forests. Their numbers are quite high, says Datta. There are no uniquely temperate or subtropical species in the book.

There is also information on habitat, dispersal modes as well as flowering and fruiting periods. It is mostly birds who disperse seeds here and then mammals and not wind or gravity so much.

“For 20 to 25 years, we’ve done a lot of studies on plant-animal interactions, especially seed dispersal and frugivorous. We found that, in Pakke Tiger Reserve, 78 percent of tree species are animal-dispersed. Out of that, at least 40 to 50 frugivorous bird species are important. Bird-dispersed species are really represented in the forest,” says Datta. “The threat or conservation status of a species assigned by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is also provided in the book.”

Arunachal is, in fact, a hub of research efforts. It has a Hornbill Research and Conservation Programme and a Hornbill Nest Adoption Programme. Scientists here are working with local communities to protect hornbill nesting habitats outside the Pakke Tiger Reserve. “We have a forest restoration project and a nature education programme as well. Most field staff is from local villages. Their involvement is what makes the programme a success,” says Datta. A hornbill festival is organized in Nagaland every year.

The threat to this treasury of plants is from road building and plantations, especially palm oil. People need roads, says Datta. There has also been a transition from agriculture to the formal economy. The problem is that roads are being built without guidelines. During the monsoon, landslides occur, the road crumbles and the rubble is dumped, damaging entire slopes of forests. Cash crop plantations, like palm oil, subsidized by the state, are being promoted. Experiences in Mizoram show these are unsuited to the ecology of the state.

Local species like Livistona jenkinsiana, Himalayan fan palm, and Phoebe cooperiana, a lauraceae family fruit tree, dispersed by hornbills, could be promoted, says Datta. Phoebe cooperiana is prized by locals and is becoming quite rare because of overharvesting.

family fruit tree, dispersed by hornbills, could be promoted, says Datta. Phoebe cooperiana is prized by locals and is becoming quite rare because of overharvesting.

“A lot of people love the fruit. During the fruiting season they pay a huge amount for a small bundle of fruits. It’s a very important timber tree also. It doesn’t fruit every year. Many people are already growing it in their home gardens,” says Datta.

Another option is medicinal plants. Arunachal has some 500 species of medicinal plants used by indigenous communities. Many of these have already been mapped. The Apatami tribe in Ziro valley uses as many as 158 medicinal plants.

“I think agroforestry, where people plant a mix of native species, could be an income earner instead of monoculture plantations,” says Datta.

The problem is that the incentives provided by the state for monoculture palm oil lure people away from native species. Environmentalists fear the slow denudation of Arunachal’s magnificent forests. The book is timely.

Comments

-

Bappu Deshmukh - March 19, 2022, 7:18 a.m.

Let’s face it! The Arunachal state government is clueless about the costs of monoculture and the damage that palm oil plantations can wreck. Just look at Indonesia and learn from their mistakes. Just because the Central government is encouraging palm oil plantations, the state govt in Arunachal is parroting the same tune. When experts like Aparajita are available there is no reason not to take their inputs when formulating a state forestry policy. But then sycophancy always pays better in the short term than common sense!