An SEZ being constructed. India has over 500 SEZs.

‘SEZs need enabling environment to succeed’

Civil Society News, New Delhi

Ten years after the SEZ (Special Economic Zones) Act was passed, India has over 500 SEZs scattered all over the country. The idea was copied from China where SEZs fuelled economic growth. The government believed that in India too SEZs would become engines of growth.

The SEZ policy did hit a wall: land acquisition was bitterly opposed by people who had to give up their fields. NGOs and activist groups said SEZs were just a ruse to grab land from small farmers. When Export Promotion Zones (EPZ), set up by the government, had failed what was the guarantee that SEZs wouldn’t meet the same fate, they asked. Dazzled by China’s success, states went ahead anyway.

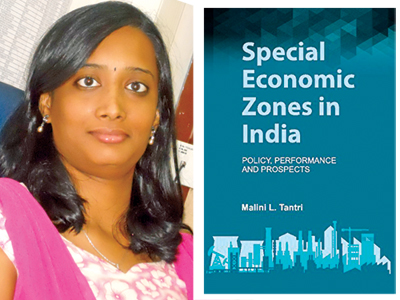

Not many have tracked the progress of SEZs. Malini L. Tantri’s book, Special Economic Zones in India: Policy, Performance and Prospects, is a detailed and realistic appraisal of India’s SEZs and of China’s SEZ policy. It compares the policies of both countries and the contrasts are stark.

Tantri is an assistant professor at the Centre for Economic Studies and Policy, Institute for Social and Economic Change, in Bengaluru. She carried out extensive fieldwork for her study, travelling to China to study their SEZs. In India, she went to SEZs in seven places – Kandla, Santacruz, Noida, Chennai, Cochin, Falta and Vishakapatnam.

“These were the only SEZs that had been previously performing as EPZs. If we look at a policy we have to examine it from a ‘before and after’ perspective,” says Tantri. Secondary data was crosschecked by speaking to exporters and to the Development Commissioner’s office in the respective SEZ she was tracking.

Speaking to Civil Society, Tantri says SEZs in India do have the potential to become engines of growth, but an enabling environment is needed.

Speaking to Civil Society, Tantri says SEZs in India do have the potential to become engines of growth, but an enabling environment is needed.

Have SEZs in India become engines of growth just like in China, as the government said they would?

The answer to your question is a bit tricky. For SEZs in India or China to become engines of growth really depends on how policy is formulated and implemented. In terms of policy, yes, it’s a very good concept. But in India we failed to understand why the EPZs failed. Perhaps we should have first understood that, then put in corrective measures and reworked the policy accordingly.

In 2000 Murasoli Maran thought the Shenzhen SEZ was a fabulous thing and the SEZ policy came into being. If you look into any government policy or literature on SEZs, they don’t talk about how China’s policy has been able to make SEZs engines of growth. So my take is that policy alone is not enough. One has to look very closely at how policy is being implemented at ground level. There we have absolutely failed.

Look at one aspect: incentives. We thought, let’s give incentives and performance will improve. Actually, that’s not the case. When you give an incentive you are giving an income tax benefit. This means, as an exporter I am able to pay a little less to the government. But the government is not doing anything to improve my competency or performance in the international market.

How can competency be facilitated? In China they did it by promoting better infrastructure and institutions which actually cut down costs and gave them a cost advantage. In India, we do not have a cost advantage.

What is the problem?

The problem with India’s SEZ policy is that the ground level understanding of how trade policy can push economics – engines of growth – has not taken place. Nothing has been built at an institutional level. They say for SEZs a single-window facility has been created. But the way it is implemented is questionable. All clearances/licences should be given through a single window, from trade to labour to investment to environment. But that’s not what actually happens on the ground. In fact, the SEZ single-window facility can’t really be called single window.

The Union ministry of commerce has a separate wing on SEZs and they are trying to see how the SEZ policy can still be pushed. But they are still batting around MAT (minimum alternate tax). They continue to think if we give waivers we will be able to perhaps attract investors. This is questionable.

The IT sector has got the maximum approvals. If you look at individual companies, many have closed operations elsewhere, maybe in a domestic area, and relocated to an SEZ because they are getting tax waivers. They are, of course, still providing employment and investment. The numbers of smaller players has not increased because single-window clearances and institutional mechanisms have not been addressed properly.

So you are saying what is needed is an enabling environment?

Exactly. But an enabling environment for the IT sector is completely different from an enabling environment for, say, the manufacturing sector. One size does not fit all. It has to be sector-specific.

China followed a very systematic approach. Initially, they pushed small industries because those had a labour advantage. Policy was formulated accordingly. Then they moved to capital-intensive industries. In the 1990s they realised the SEZ industries were causing environmental degradation. So they restricted FDI in industries that hampered the environmental standards of the Shenzhen region.

An enabling environment differs from sector to sector and from state to state. In Karnataka, for example, Bengaluru has a good enabling environment for the IT sector. We have engineering colleges, you get fresh graduates and we have road connectivity. IT companies don’t require a port facility.

But you can’t have textile companies in Bengaluru. You need a port for export and they would need to go to Chennai, Kochi or Mangalore. Look at the transport facility you have. One needs to examine the details of this enabling environment.

Are the SEZs providing employment? Does labour receive a fair deal?

Again, it differs from sector to sector. Many companies in the IT sector relocated from domestic areas to SEZs, so what has taken place is a shifting of employment opportunities. Some manufacturing by Indian companies has started so intermittent employment has improved because of the SEZs.

The general impression of the layman is that since SEZs are considered a public utility there are no labour laws. That is not true. Labour laws exist, it’s just that trade unions, strikes and lockouts are not supposed to take place within the boundaries of the SEZ.

In the gems and jewellery sector the feedback I received on labour was pretty good. When I went to Hassan in Karnataka where there is a textile SEZ I spoke casually to workers there. They reported that conditions were not that great. The problem, it seemed, was lack of dedicated power from nine to five. The management made it mandatory for them to work a second shift irrespective of whether the workers were men or women. I have not examined the wage component very much so I would not like to comment on that. Many SEZs are just taking off so we have to wait and watch.

You have also mentioned in your book that land acquisition and rehab are still issues for SEZs?

The EPZs were mainly set up by the government, so these are government SEZs. In Falta, the government acquired land in 1986. I visited the SEZ in April 2008. You will be surprised to know that the government is still sending cheques to people whose land was acquired. One of the respondents showed me the cheque.

The new SEZs are private ones. When I was doing fieldwork on new SEZs in the south I found rehab is an issue because the policy still has a lot of ambiguity. The Mangalore SEZ is government-owned with private sector participation. Land acquisition issues did come up. Why? Again, it’s a policy failure. I mean, who are you going to give compensation to? The farmer? I have agricultural land in my village but someone else tills it. So I get compensation but what about the tiller who loses his livelihood?

In India we have ownership rights over land but in China they have ‘right to use’. The government had to acquire this ‘right to use’ from people on the land when it set up the Shenzhen SEZ. They assured employment to each individual. Not just that, they set up a technical institute because farmers weren’t well-educated and couldn’t be absorbed into jobs and management. In fact, the whole purpose of having a Shenzhen University was to have an educational institution that provided skills and evaluated the performance of the Shenzhen SEZ.

It means that academics were directly involved. Here, professors from the IITs and IIMs are supposed to be on the SEZ board of approvals. But in reality there is no active involvement.

We failed to understand the problem in land acquisition. It is not just about giving compensation to the farmer and the tiller. People need to have skills so they can be absorbed into this kind of employment. We have educational institutes but the overall structure of pushing a policy is missing in India. Everything is standalone.

Won’t it make sense to whittle down the number of SEZs?

I agree. See, initially China had just five SEZs. But there are differences. Shenzhen had six districts. Four were converted into an SEZ and two were left out. That means that 60 to 70 per cent of the city has been converted into an SEZ. China has a real population living in the SEZ. In India we have only the working population in the SEZ.

But I think the SEZ policy was pushed through with haste. We thought more numbers will push performance. We didn’t look into what actually pushes performance. Definitely we need to slow down.

The other issue is – around 500-plus SEZs have been cleared but how are you going to integrate them? The existing ones need to coordinate with each other.

If you look at the SEZ policy of Karnataka, Kerala or Tamil Nadu, they are all competing in providing incentives and tax waivers. No state talks about the absolute advantage it has in a particular sector and then decides to promote an SEZ around it.

You look at the five SEZs in China. One, location pushed their performance. Second, their government actually thought thematically about which industry would be promoted where.

The exporters find many of the government’s incentives most difficult to access. Many of them don’t even think of applying because it is so much of a hassle. Better to create an enabling environment and fulfill your promises.