How PV’s middle way sought to strike a balance

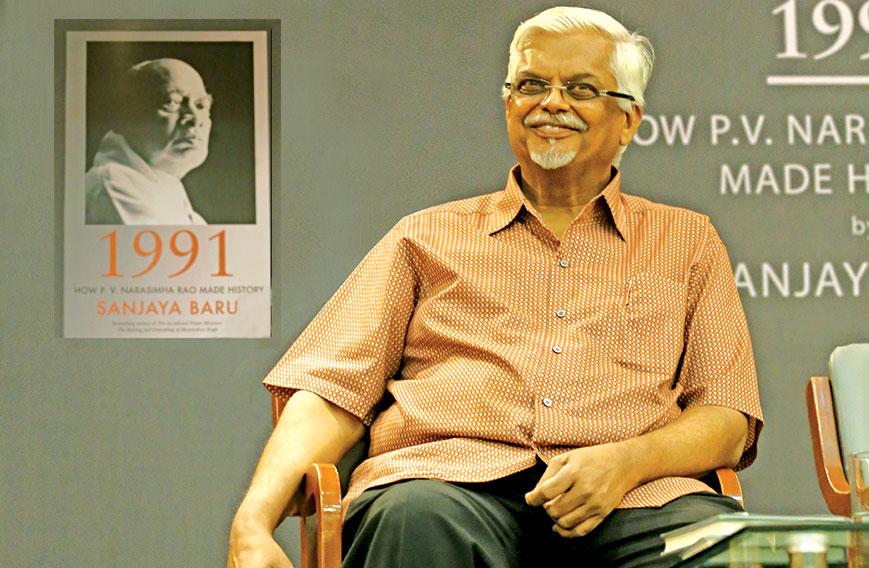

Sanjaya Baru

A few years before P.V. Narasimha Rao passed away a former official of the finance ministry asked him how much credit he would like to take for the reforms of 1991-92, and how much credit would he give to Manmohan Singh. PV praised Singh and acknowledged his loyalty and his contribution to reforms. Then, in his characteristic deadpan manner, he said to his interlocutor, “a finance minister is like the numeral zero. Its power depends on the number you place in front of it. The success of a finance minister depends on the support of the Prime Minister.”

By taking charge of policy in the summer of 1991, PV made history. But, he made sure he took no individual credit for it, claiming that what he did is what Rajiv Gandhi would have wanted to do. He told the Tirupati session of the All India Congress Committee (AICC), in April 1992, “In the past ten months, our Government has initiated far-reaching fiscal and financial reforms. This was done in conformity with our Election Manifesto of 1991 which gives the main features of the reforms.”

Self-reliance

Suggesting that there was no deviation in his policies from Nehru’s vision of a ‘socialist India’, PV projected his initiatives as ensuring ‘continuity with change’. A country of India’s size “has to be self-reliant”, PV told the AICC, but self-reliance did not mean the pursuit of import substitution as a dogma. “The very level of development we have reached has made us independent of the world economy in some respects, but more dependent on it in others.”

Self-reliance in 1991, PV believed, could be defined as being “indebted only to the extent we have the capacity to pay". Reducing foreign debt, being able to avoid default, promoting exports and liberalising the economy so as to attract foreign investment and earn foreign exchange were all elements that would define the path to self-reliance. In the past, self-reliance had been defined as securing ‘independence’ from the world economy, now self-reliance was being redefined as creating ‘inter-dependencies’ that would give others a stake in India’s progress.

Next, PV went on to redefine the role of the public sector, reminding his party that both the profits and the losses of public enterprises were in fact the profits and losses of the people of India. Making the public sector more efficient, so that it would cease to be loss-making, was in the interests of the people. Further elaborating the role of public and private sectors in the economy, PV claimed his policies “do not represent the withdrawal of the State altogether, but a reconsideration of the areas in which it must be present".

Finally, PV went on to redefine yet another Nehruvian idea that had been reduced to a shibboleth by Indira Gandhi’s diplomats. Non-alignment was not just about remaining outside antagonistic military alliances. It was not about being ‘neutral’. Non-alignment is “an urge for independence in judgment and action, in exercise of the sovereign equality of nations". As a non-aligned nation India could be on one side or another in international relations, depending on the issue. While India chooses to be outside any alliance, it retains the freedom to work with one or the other alliance depending on its own national interest.

This was a pragmatic, not ideological, view of non-alignment. After all, in 1962 Nehru was willing to seek US military help to deal with China and in 1971 Indira sought Soviet help to deal with the ganging up of the US and China on the issue of the future of East Pakistan. The Polish economist, Michel Kalecki, described non-alignment as “a clever calf sucking two cows”, drawing attention to the policy’s pragmatic rather than ideological basis.

Fine balance

Linking his economic policies to his foreign policy, PV concluded, “This self-reliance must consist in trying to find solutions to our own problems primarily according to our own genius.... We reject nothing useful for its plainness, we take nothing irrelevant for its dazzle.”

PV called it 'The Middle Way.' PV’s ‘Middle Way’ is not to be confused with a ‘middle path’. It was not a mean or a median, a compromise between extremes. It was a path unto itself. “To interpret Nehru’s middle way as being valid only in a bi-polar situation is not to understand our ancient philosophy of the Middle Way", PV told the AICC.

Writing a few years later, in 1998, to be precise, British sociologist Anthony Giddens called it the ‘third way’ in his politically influential book, The Third Way: Renewal of Social Democracy. It was said to have inspired the politics of Prime Minister Tony Blair who was himself battling the Right and Left within the Labour Party. Rejecting top-down bureaucratic socialism, and its emphasis on public investment and controls, as well as rejecting laissez-faire ‘neo-liberalism’, PV’s ‘middle way’ sought to “strike a balance between the individual and the common good”, as PV put it.

“The Middle Way was meant to be a constant reminder that no assertion or its opposite can be the full and complete truth. It meant that we looked for Truth in the interstices of dogmas. It means today that we will accept no dogma even if it happens to be the only dogma remaining in the field at a given moment.”

It was the best expression of a liberal principle that in a different world a very different man summed up as “seeking truth from facts”.

Book extract from 1991: How P.V. Narasimha Rao Made History, Aleph Book Company, 2016.