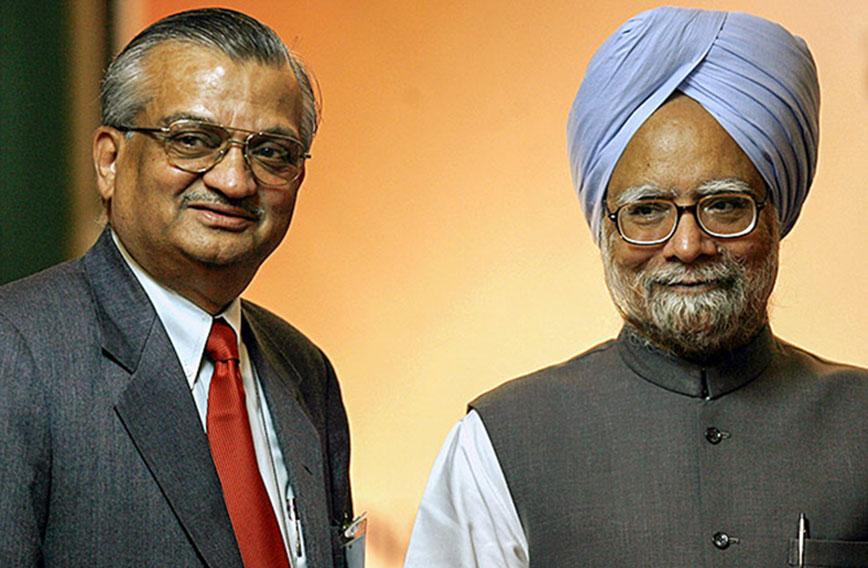

Anil Kakodkar with Manmohan Singh

Insider's account of India's nuclear setup

Sanjaya Baru

A decade ago this book would have hit the headlines. It is a testimony to media’s short memory that Anil Kakodkar’s brief but interesting autobiography has not yet made waves. Indeed, many young readers of today may not even understand why the book ought to be news. In the politically contentious months of 2006-08 when the fate of the negotiations towards an India-United States civil nuclear energy cooperation agreement hung in the balance, every word that Kakodkar uttered on the arcane specifics of the deal made a difference to the stability of the Manmohan Singh government. Fire and Fury is, therefore, an apt title for Kakodkar’s autobiography. But, let us not get ahead of the narrative.

Anil Kakodkar is without doubt one of India’s most distinguished and talented scientist-engineers. I say ‘scientist-engineer’ advisedly since Kakodkar himself argues that in the field of nuclear science and technology “treating scientists and engineers differently is counterproductive”. This “silo mentality”, he observes, has “deep roots in our society” — alluding to the caste system. Kakodkar, like many of his colleagues at the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC), was a scientist-engineer who mastered the physics, chemistry and the engineering of India’s largely home-made nuclear energy and weapons capability. He had a key role in the nuclear tests of 1974 and 1998.

Kakodkar was born into a Maharashtrian family of modest means and grew up in an atmosphere of patriotism and service to society. His father worked at Mahatma Gandhi’s Sevagram after graduating from Kashi Vishwavidyalaya and was imprisoned for nine years in Goa by the Portuguese rulers he was fighting to oust. Consequently, Kakodkar’s mother became the central figure in his life in his early years. She ran a school, made ends meet and deeply influenced her bright son. Kakodkar has dedicated his book to her.

After a brilliant run at school and college, Kakodkar took up a job in a private company to help his family’s finances. After securing a job at Premier Automobiles he opted out, disgusted at the feudal obeisance demanded by the owner, Seth Lalchand Hirachand, from his employees. By happenstance he landed up at a training school at what was then called the Atomic Energy Establishment. Chapters 2 to 5 recount in great detail Kakodkar’s experience rising up the ranks at BARC and his deepening engagement with India’s nuclear programme.

His observations on Indian work culture are valuable. After a one-year course in Britain, where he declined a job offer and returned home to BARC, Kakodkar observed that while the organisational culture within the British institution was based on trust, in India the British had left an administrative system based on distrust. Indian bureaucracy only perpetuated that culture.

Kakodkar is candid about the scientific work culture within which he grew up. Tales of squabbles within research teams and worries about “sharks” in the organisation suggest that BARC was full of highly competitive and, perhaps, egotistic individuals. When his boss, V.S. Meckoni, who gets full marks for mentoring him, pushes him up the ladder for promotion, Kakodkar’s hesitation tells a tale. “I am a small fry,” he says, “and if I get in, these big fellows will chew me out.” Was that a necessary downside of bringing the best and brightest together to undertake a project under difficult circumstances and with limited funds?

The story of India’s nuclear programme is a story of perseverance in an environment of modest financial means and external sanctions and Kakodkar tells it well. India was fortunate to have had such leaders as Homi Bhabha, H.M. Sethna, Raja Ramanna, P.K. Iyengar, M.R. Srinivasan, R. Chidambaram and a host of others who worked with dedication and secured India’s strategic autonomy. Kakodkar repeatedly celebrates the “team spirit” that enabled him and his colleagues to make India a nuclear weapons state. He has valuable advice on how India can improve its educational and research capabilities.

The chapter on the nuclear deal is what will generate controversy. One consequence of the nuclear establishment working under debilitating sanctions imposed by western nations led by the United States was the deep suspicion it developed towards the West in general and the US in particular. So it was not surprising that Kakodkar remained deeply sceptical of US motivations and intentions in entering into the nuclear deal with India. The framework agreement of July 18, 2005, was inked by Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and President George W. Bush after many internal differences were ironed out by both leaders within their respective teams. Kakodkar believes he alone stood between a bad deal and one that served India well. He quotes Singh giving him that credit, saying, “You have saved the country.” (p.101)

The differences within the government spilled out into the media. Objecting to draft formulations coming out of the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) and the Prime Minister’s Office, Kakodkar says, “I had to put my foot down and that was the reason I went public with my stand. While doing so I kept my resignation letter in my pocket.” (p.107) “I began to look like a villain,” he complains. (p.99) “I was being singled out as the fall guy.” (p.100) He quotes Ron Somers, who headed the US-India Business Council and lobbied hard for the deal, telling him that he had been told that “Anil Kakodkar was the only hurdle” in the completion of the deal. (p.105)

Kakodkar has not shied away from naming individuals in government who were supportive of his stance during the negotiations. By not naming the others who were equally involved we must conjecture that he is either censuring their role or believes they played no role at all! He does not hesitate to call the external affairs ministry a “divided” house, adding, “I had sympathisers and supporters in MEA who would urge me to be careful and firm… Through them I would also receive the next day’s news in advance.” (p.108)

Kakodkar has words of praise for Foreign Secretary Shivshankar Menon but none for his predecessor, Shyam Saran. On the drafting of the contentious civil nuclear liability agreement, handled by Menon and Prithviraj Chavan, then minister of state in the PMO, Kakodkar says, “The way it happened was rather impractical, very disruptive and without sufficient stakeholder engagement.” (p.112) It was left to S. Jaishankar, as foreign secretary, to finally tie up the loose ends of the civil liability law.

In response to opposition criticism that the deal was being ‘rushed through’, the PMO clarified repeatedly that the time-table was partly set by the US political calendar, with Bush’s term coming to an end, and by the fact that India’s nuclear plants were running out of fuel. Kakodkar admits that the latter was indeed true. The Union government’s inability to secure adequate uranium, with domestic supply constrained by environmentalists holding up mining and imports restricted by even Russia and France saying they could supply only if India secured an exemption from the Nuclear Suppliers’ Group, made an early conclusion of the US-India deal imperative.

Kakodkar and his associate, Suresh Gangotra, have written an interesting book that should be widely read. The book will stir controversy with its observations on internal differences within government. Interestingly, Kakodkar’s claim that he alone protected India’s strategic autonomy by securing a good deal finds resonance in Manmohan Singh’s foreword where he credits Kakodkar for being “the key contributor to India’s emergence as a full-grown nuclear power”. If there ever was a ‘key’ contributor, it was George W. Bush Jr. That’s another story.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!