Kerala's fishermen: Heroes of a terrible flood

Civil Society Reviews

Disasters make headlines and are remembered because of the disruption they cause. Life just can’t be the same after an earthquake, flood or fire — till, of course, survivors move on and the next generation has no reason to look back.

But what about rescuers? The heroes of the day, who put their own lives at risk to save others. How much space is there for them in public memory? Do people on the verge of death ever remember the people who saved them? Do they go back to say thank you and help them in their lives? Do governments reward them adequately? The answer is mostly no.

In the floods that swamped central parts of Kerala not so long ago, fishermen went from the coast to the interiors and saved thousands of lives. They took with them their boats, their unique knowledge of dealing with currents and waves and their hardy bodies with enormous reserves of strength.

The fishermen went with resolve and a spirit of service. They left behind anxious families who depended on the meagre earnings of these men from fishing. Had something happened to them, their families would have been destitute — down from very little to nothing.

The call to serve came from the government on loudspeakers and TV and through the churches. It was just an appeal and they need not have heeded it. There was no compulsion to go. But they went, at no notice, without telling their families who would have almost certainly tried to hold them back for fear of their safety. They took their own boats or borrowed boats, put them on trucks and travelled several hours to the flooded areas.

So heavy had been the rain that swirling water had submerged the lower floors of residential buildings and in some cases gone over the roofs. These were wealthy areas — Gulf earnings had been used to build lavish homes where elderly parents lived in isolation.

By contrast, the fishermen came from shanties on the coast with dwindling incomes from fishing and mounting debts. It is a great irony that people with so much wealth should have been so helpless and the fishermen with very little should have had the fortitude and indomitable spirit to contend with nature’s fury.

The fishermen had just recently had their lives thrown into turmoil by Cyclone Ockhi. Boats and lives had been lost. Some of them had spent two and three days in the turbulent sea, buffeted by giant waves but keeping themselves afloat by treading water and hanging on to the remnants of their boats, their bodies bruised and battered, till they were rescued. They hadn’t recovered from Ockhi’s battering but joined in the rescue readily, putting their lives at risk again.

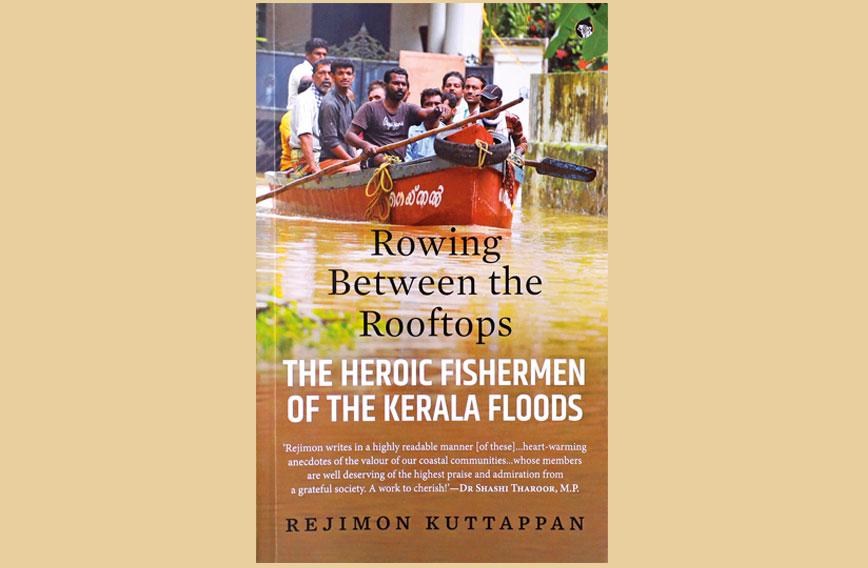

In this outstanding book, Rejimon Kuttappan has told the stories of these fishermen whose courageous feats made news at the time of the floods but deserved to be remembered with something more substantial and respectful of their efforts than the day’s papers and TV shows.

Speaking to the fishermen much after the event, Kuttappan’s narrative carefully stitches together the events of those days when the floods were at their worst and every hour was valuable in getting people out of their homes and into boats and reaching them to relief camps.

The fishermen would be navigating neighbourhoods they knew nothing about. They would take a policeman or some local person along. Many a time the boats would get stuck in iron gates and even on rooftops. They would dock at buildings, use ropes to climb to higher floors and carry people down. It wasn’t easy because how do you bring down into an unsteady boat a heavy old person who doesn’t know to swim or a pregnant woman who is almost ready to give birth and has her other children clinging to her.

The book also goes beyond the events of those days to introduce us to the fragile existence of the fishing communities. Mechanised fishing has impacted the incomes of traditional fishermen, forcing many to become daily labourers. They have growing debts that they can’t settle and no access to affordable healthcare and reliable housing.

Kuttappan goes into the personal lives of the fishermen. The unpaid debt, the sightless child, the shattered house. These men were heroes of the central Kerala floods. But back on the coast

they were vulnerable and struggling against the everyday odds of running their lives and fending for their families.

Kuttappan’s book is an example of how journalists should go beyond the sensational to explore the multiple layers of a story. The fishermen are both heroes and victims in a flawed system. As heroes they make good for the government, which doesn’t know to deal with disasters. As victims they suffer because of the callousness shown towards their needs as productive citizens with a traditional skill.

We should look back on disasters because there is a lot to learn from them. The obvious lesson from Kerala is that India needs to prepare for the vagaries of changing weather patterns. We can also see that our urbanisation is flawed and building as we do in our cities, we invite tragedy to strike. But most of all Kerala’s flood should awaken us to the strengths of a composite society — the fishermen were Christians and they were saving Hindus and Muslims without a thought about which religion they came from.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!