Female street politics

ANITA ANAND

|

|

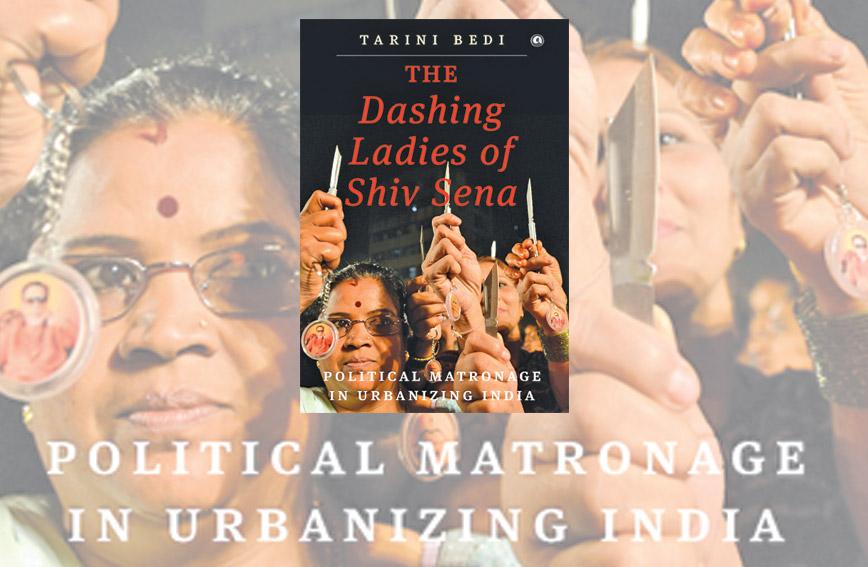

Who would imagine that Bala, a leader of the Shiv Sena women’s wing in Mumbai, would ride astride her motorcycle in her sari, fiercely? Tarini Bedi, author of The Dashing Ladies of Shiv Sena, as part of her doctoral research, also jumped on Bala’s bike to get to know firsthand the world of Shiv Sena women.

Bala tells Bedi that on her bike, she is like Shivaji and the Rani of Jhansi on her horse. People can hear her coming and that is what makes her dashing! Bedi writes that this danger-inflected persona of ‘riding’ is entirely exceptional for women and what the Shiv Sena women call “dashing”.

It’s a world where women emerge from their homes and families for the common good of community politics. They bring to it their female experience — and some machismo — to bond over community rights and wrongs. They work and play together, in a sisterhood of changemakers. At the lowest rung of the political party, it is these women who are the movers and shakers of the Shiv Sena.

Dashing Ladies is an ethnography of the everyday lives of women like Bala who have learned to navigate the political space that is occupied predominantly by men. Bedi points out that while the book focuses on women political animators, it also addresses broader scholarship on women’s participation in cultural-nationalist politics in India. It builds on the already extensive scholarship on Hindu nationalist women, which has been vital in probing the political presence of women who enter the public sphere through routes that are at odds with liberal feminism.

Bedi conducted her research over an extended period in the cities of Mumbai, Pune and Nashik. Starting in 2003, she travelled to these cities with the cooperation of the party women and got to know their workings at close level. The book has numerous narratives of how the Sena women organise and resolve community disputes and restore order. Adopting female and male tactics, they have built for themselves and their party a broad-based cadre of women workers and leaders.

The book takes us through the rituals and psychologies of the Shiv Sena women — why they do what they do and how this has enabled them to get where they have. Over decades, women have watched and slowly consolidated their power — by watching men and how they function. Therefore, it is of little surprise that the ‘matronage’ practised by the women is not that different from the ‘patronage’ of the men in their parties, or society in general.

The various descriptions of how Bala and other women leaders conduct their business is rather revealing. Whether it is to garner votes in an upcoming election, or respond to the community needs of water taps, toilets, schools, health centres or a road — it’s done with the calculated mind and muscle of the men in local politics. They cajole, threaten and bully their party workers and community members. Surrounding themselves with sycophants, they consolidate their power and position. This would stand to reason as there are no other real role models in politics for women. And, as mostly working class women, they are attached to their families and communities — and to their men — in a visceral way.

Bedi argues that the ‘matronage’ of Shiv Sena women is different from ‘patronage’ of men. She defines matronage as “those strategies of political effectiveness and political connection produced among those who in all conventional understandings of patronage and clientelism, are the most unlikely of patrons. It is often produced among those who are economically, socially and spatially marginalised in the cities they live in, and structurally marginalised in their political party. But, these patrons are, nevertheless, often central to the grids of electoral politics that emerge in spaces of precarity and uncertainty in particular locations.”

In this she could be right. However, given the reality of national or local politics, it is questionable whether the strategies of the ‘matronage’ of Sena women are that different to the ‘patronage’ of men. And, if they are, how then would these enable the women to move ahead (and indeed up) into party echelons?

But, that aside, the book is an impressive work by the author, who has lived in Maharashtra and now is in the US. It makes an important contribution to the burgeoning body of literature on women in politics in India, especially since the 1992 Constitutional amendment and quota for women in municipal and grassroots politics. As an extension of a doctoral dissertation, it is heavy on theory (old and new) and language.

The book is useful for those who want to understand the women’s cadre of the Shiv Sena, local Maharashtrian politics, and the evolving phenomena of women in local politics in India. While there isn’t anything new or revealing about the situation of women in Indian politics, the book is a window into the intimate lives of the dashing women of the Shiv Sena.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!