The Keoladeo National Park, famed for its birds

Deep dive: Inside story of wildlife reserves

Civil Society Reviews

INDIA’s wondrous natural heritage is still a hidden gem for most Indians. Not for them the deep jungle, the steep climb or a chance encounter with a slithery snake. No offence, but heritage for middle class India implies the Taj Mahal, the ruins of Hampi or perhaps the Ellora Caves.

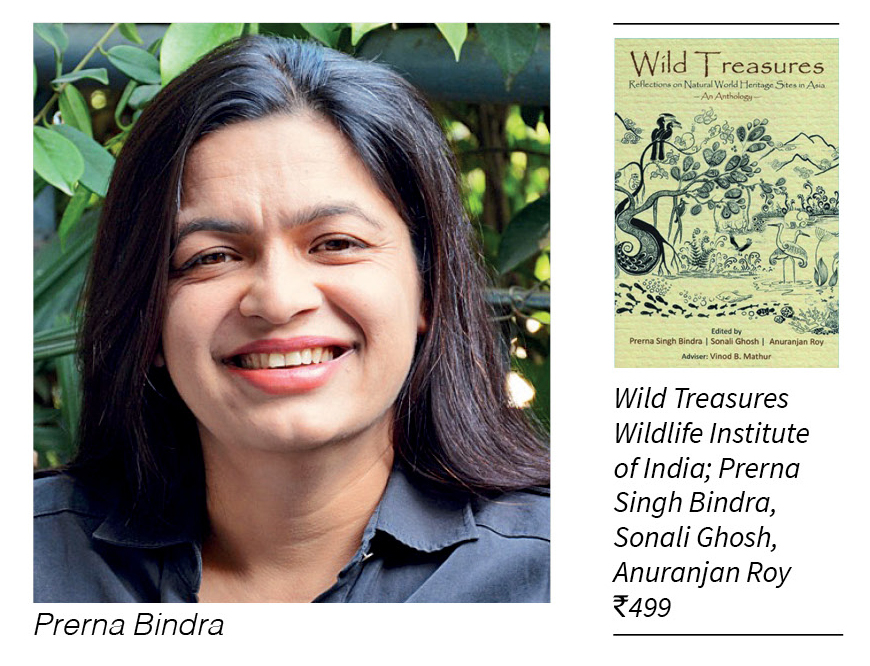

This anthology, Wild Treasures, lures readers into another world of heritage sites, of forests, mountains, grasslands and a plethora of wildlife. The editors, Prerna Singh Bindra, Sonali Ghosh and Anuranjan Roy, have put together a series of pieces by a galaxy of writers: wildlife conservationists, scientists, researchers, forest officers, biologists, historians, journalists and even Amitav Ghosh.

This is nature writing at its best, compelling and informative.

Almost all of India’s major national parks, protected areas and wildlife sanctuaries are covered: the Great Himalayan National Park, Kaziranga, Keoladeo, Khangchendzonga, Manas, Nanda Devi, the Valley of Flowers, Sundarbans and the Western Ghats. The anthology then crosses borders to write about natural heritage sites in Nepal, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Myanmar and Iran.

“People aren’t aware of natural heritage sites like Manas or Kaziranga or the 39 sites in the Western Ghats,” remarks Bindra. “We wanted the anthology to be readable and inspire people to care about our ecological wealth.”

Bindra got a visiting fellowship from UNESCO’s Category 2 Centre which works under the aegis of the Wildlife Institute of India (WTI) in Dehradun. Her mandate was to organize a nature writing festival which she did in February 2017. “It actually morphed into a nature and cultural festival. We had writers like Stephen Alter and Ranjit Lal. Forest officers spoke of their experiences. Regional poets recited poignant poetry in beautiful Hindi. It was all very moving.”

The festival got people interested in natural heritage sites. Sonali Ghosh, a forest officer, headed the Category 2 Centre at that time. She was keen to build on the momentum created by the festival and that’s how the idea of an anthology was born.

Putting together varied writings wasn’t very difficult, says Bindra. A community of people came on board because of their shared interest in nature. Sanctuary magazine, where Bindra once worked as a journalist, gave her access to their archives. The book is also beautifully illustrated by Vivek Sarkar and neatly edited.

“This range of writing depicts India’s diversity. We are such a blessed country to have such a diversity of landscapes. I especially liked getting forest officers on board because they represent voices from the field that we rarely hear,” says Bindra.

As forest officer, Sonali Ghosh’s first job, in the male-dominated forest service, was as Assistant Conservator in Kaziranga, famed for its one-horned rhinos. She writes of her life in the park, of managing its vast terrain, of being chased by an irritated rhino and getting stuck on the back of a recalcitrant elephant. She’s written another piece on her time in Manas as well. It’s an interesting history of the park, how it fell on bad times during the insurgency and its revival by Kampa Borgayari, an astute Bodo political leader.

Samir Sinha, former Field Director of the Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve, writes of the Valley of Flowers, the intelligence of local people and countering the bane of tourism. Sanjeeva Pandey’s article is on the Great Himalayan National Park in Himachal Pradesh, the deep connect of the people with nature and the importance of an integrated approach to conservation.

Sandeep Pande was posted to Sikkim. His piece, “Securing Khangchendzonpa: Happy Forests, Happy People,” is a remarkable story of how this region, revered as sacred, was creatively rescued from poaching, ranching and tourism with political backing by Chief Minister Pawan Chamling. When the lucrative cardamom crop was struck by disease, new plantations were raised with MGNREGA funds.

Bindra also recommends reading Stephen Alter’s essay, “Writing Outdoors.” There is good advice here for aspiring nature writers. Read Samia Saif, a brave researcher and conservationist, on the difficulties of saving tigers in the Sunderbans.

Read also Ullas Karanth on the predators of Nagarhole, Asad Rahmani on the Bengal Florican in Kaziranga and on Manas, Anuranjan Roy’s affectionate piece on the creepy crawlies of the Western Ghats, Erach Bharucha on sacred groves and E.R.C. Davidar on saving the Nilgiri Tahr. Bhutan’s Queen Mother, Ashi Dorji Wangmo Wangchuck, has penned a memorable piece on the Royal Manas National Park. Bindra too has written a lively and engaging piece on her journey through sites in the Western Ghats.

There are also archival material and historical narratives. Salim Ali’s humorous piece on the birds of Keoladeo is reproduced. And, moving back in time, Francis Younghusband’s rapturous ode to Kanchenjunga is almost funny. Read also E.P. Gee’s first-hand account of discovering a primate near Manas and how it got named after him.

So how does one protect this valuable natural heritage? The universal axiom is that local people protect forests best. In the past, forest departments and locals were at loggerheads many times but things are changing.

“In all these years in my interaction with forest officials and staff I find that they interact with locals especially in buffer zones and involve them in conservation. It’s part of their mandate,” says Bindra.

“In all these years in my interaction with forest officials and staff I find that they interact with locals especially in buffer zones and involve them in conservation. It’s part of their mandate,” says Bindra.

In many remote forested areas, she says, there is no other government department apart from the forest department. It’s the rangers and guards who represent the administration. “There is cooperation. Locals give information of any illegal activity and the forest department helps if they have a health crisis. Villagers also come out to assist if there is an emergency like a forest fire because it impacts them too. The level of participation has increased. The forest department trains locals as guides and there are tiger conservation foundations which help with livelihood and skilling projects.”

In fact, some of the pieces penned by forest officers, especially Sandeep Pandey’s, are case studies in people’s participation in protecting forests.

The real threat to natural heritage sites is from a spate of linear projects likely to come up in ecologically sensitive areas. To make matters worse, a new draft environment impact assessment notification seeks to weaken laws and silence local communities. Environmentalists have objected and called it regressive.

Since it’s mostly industry which lobbies for such policies, shouldn’t protesters also talk to the business community? “We can’t ease pressure on the government. Political will is very critical. Sure, industry lobbies but it is the government which dilutes or changes laws. We do see a weakening of political will. But we have to engage with the government to conserve these areas,” emphasizes Bindra.

Perhaps the pandemic will change business perceptions. It has ruined businesses. Environmentalists point to the exploitation of nature and the consumption of wildlife for an upsurge in zoonotic diseases. “So every ministry, whether it’s mining or infrastructure, should be mindful of its impact on the environment and not the environment ministry alone,” says Bindra.

“There is a lot of greenwashing that goes on. Look at Oil India’s blowout in Baghjan Tinsukia in Assam. It started in May and ruined one of our finest wetlands, the Dibru Saikhowa Wildlife Sanctuary. Local people are suffering because their groundwater is ruined. It’s an ecological disaster by a public sector company,” says Bindra.

Another threat is the degradation of forests, and construction of roads and railways through ecologically sensitive areas increasing human-animal conflict. Corridors where animals traditionally crossed over have been segmented by such infrastructure.

“Animals like tigers, lions, leopards, bears are all migrants. They need to travel for sustenance or to find a mate. Earlier they had safe passage because forests were connected. Now they don’t so there is more interaction with people and more conflict. I always say, if an animal is invisible it’s safe," says Bindra. Her suggestion is to educate people to just let the animal pass. Instead, the sight of a snake or a leopard or a herd of elephants results in crowds, hysteria and violence. The poor animal is beaten up and forced to retaliate.

But, all said and done, in the final analysis, most Indians, especially in rural India, don’t mind having animals as neighbours. “We do have conflict but we also have remarkable co-existence. We have 1.3 billion people, grinding poverty, a fast developing economy and in this matrix, an amazing diversity of wildlife. What doesn’t get reported is the remarkable acceptance of our people towards animals and that is what has contributed to saving our wildlife," says Bindra.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!