Visiting Kobad in jail as he goes from case to case

Gautam Vohra, New Delhi

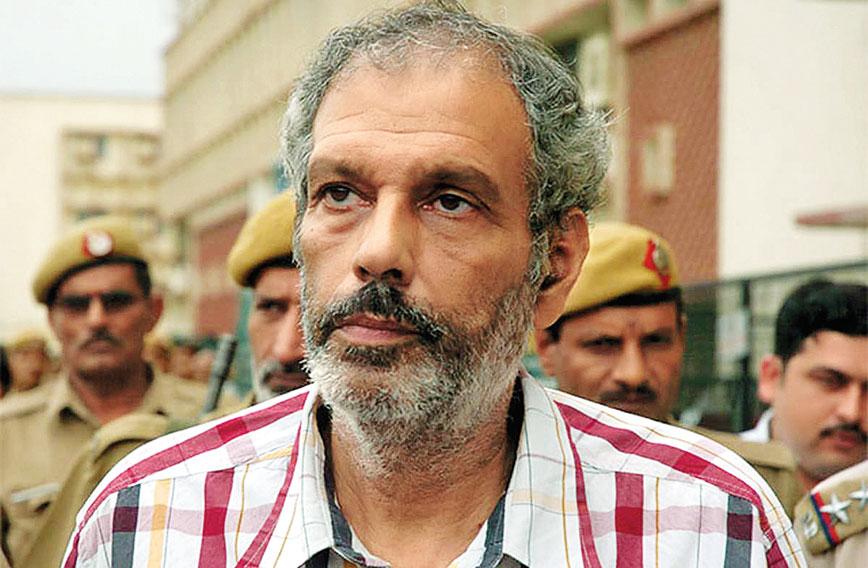

Kobad Ghandy is moving towards window number four with the help of a walking stick. When he sees us he smiles and I notice that one of his front teeth is missing.

The window is covered by two wire meshes. One on his side. The other on ours. The distance between him and us is further enhanced by an elongated cemented channel that goes across the length of all the windows.

We have to pick up phones to speak to Kobad. I am meeting him in prison again, almost a decade after I established contact with him at Tihar jail. There, too, a wire mesh divided us. But at Tihar I was alone with him in a room. At Hazaribagh jail, built in the 19th century by the British, we are standing outside, alongside the other prisoners, some four to a window, several shouting to get themselves heard.

Since then Kobad has been taken to several prisons across the country. He was relatively better treated in Andhra prisons as there he held the status of a political prisoner. In Hazaribagh, as elsewhere, he is a common criminal, an undertrial for almost a decade. The irony is that not a single charge under the UAPA (Unlawful Areas Protection Act) has been proved against him in all these years, except a minor charge or two of assuming a false identity.

I am hoping to hear that he is better off in Hazaribagh jail than he was at Tihar. His letters from Tihar were full of incidents of denial of basic rights, even harassment. So the four of us are perturbed to hear that conditions are much worse: he is routinely refused access to the outside world, his letters do not get posted, he is not allowed to use the phone, letters to him reach late if at all and the simplest of requests is ignored.

Meenal Madhukar, a healer, talks to Kobad about reflecting positive energy. For he has expressed only the negatives; if he thinks positively, exuding positive energy, the conditions around him will change. Kobad listens with a smile to these new ideas. He is keen to get answers from Harshit Dhingra who is coordinating his legal battles. Kobad is told that this trick of the State — as soon as he wins one case, the police whisk him away to be tried for another case in another state — has to be tackled. That is how they have been able to prolong the case.

The plan is to file a petition in the Supreme Court so that the State informs us about the cases and charges of terrorism that have been filed against him. If these are similar — as they have been under UAPA — they should be dismissed as the other courts did. Then Kobad will be spared the turmoil he has had to undergo so far. In fact, according to the “confessional statements” that Kobad is alleged to have made, he is next due in Odisha and Chhattisgarh. At the age of 71, his health cannot take it.

Kobad asks his local lawyer, Rohit Thakur, if he has filed the case on medical grounds. For, unlike other prisons, the medical care in Hazaribagh jail is minimal. And Kobad is particularly concerned about his deteriorating prostate condition. Rohit informs him that he has not yet been able to get the report from the jail hospital doctor. He has also been unable to get access to the Superintendent who can address the problems being faced by Kobad.

As we bid farewell to Kobad, expressing our solidarity, I see a resigned look on his face. We are keen to meet the jail superintendent and send in our request. He is busy in another wing of the jail and does not respond. After lunch we go to his residence. We are summoned to his verandah where he reclines under the fan while swallows dash in and out. Before us is the vista of a large space dominated by a forest overlooking the lake. The trees have enormous girth, towering over the surroundings, probably planted by the Brits a century or two ago.

I cannot help admiring the style that the superintendent, Hamid Akhtar, resides in. Even officials in the IAS cadre could not manage such accommodation. My father, a member of the steel frame, the ICS, lived in comfort in Ferozepur district, the state headquarters, in Chandigarh and in Delhi. But the superintendent’s abode is something else.

The outcome of our meeting is that the superintendent gives his direct phone number to Rohit. Now access will not be an issue and hopefully Kobad’s immediate health problems can be attended to.

We have accomplished what we came for. But my stride no longer has the same spring as when we boarded the plane to Ranchi. I recall being amused by a sign at the Birsa Munda airport saying ‘Do not spit’ and had wondered whom it was directed at. For those who could read it were not the likely offenders.

We book in at the Canary Inn and I am drawn to Hindu Hotel, serving Hindu meals. Next to it is a poster with Narendra Modi promising electricity to all villages. I had seen such posters of the PM in Ranchi. In Hazaribagh he is no less dominant. I try to get my companions to have a Hindu meal. I am curious, never having been offered one. But they are not persuaded. I miss out on a rare treat.

The next morning we are in a celebratory mood. Harshit and Meenal purchase laddoos, barfi and gulab jamuns to give to the jail and the jailors. After we have visited Kobad, and thereafter the superintendent, we visit Harshit’s relatives who treat us to more mithai. Harshit takes me to the window of a 14th floor apartment to show me his school where he played cricket. The city of Hazaribagh is laid out at our feet even as more laddoos are brought to us by the young cousin. While we are in these resplendent surroundings, Kobad is in his dingy room. In Hazaribagh jail. Caught in his dilemmas posed by the Indian State.

Comments

-

David Maude-Roxby-Montalto - Nov. 6, 2018, 6:08 p.m.

This is how laws that are drawn up to help man become abused and wrongly used. Very sadly mankind is left free to be bad or good and is always going to be tempted. Those who have experienced love know that a person can only love who can first love themselves. The lack of love is due to frustration, Insecurity, no self confidence, no self respect ; which today is the common lot for most souls. We are the problem; we ignore love.

-

Patricia Montalto - Nov. 5, 2018, 2:33 p.m.

Brilliantly written account of the cruel reality