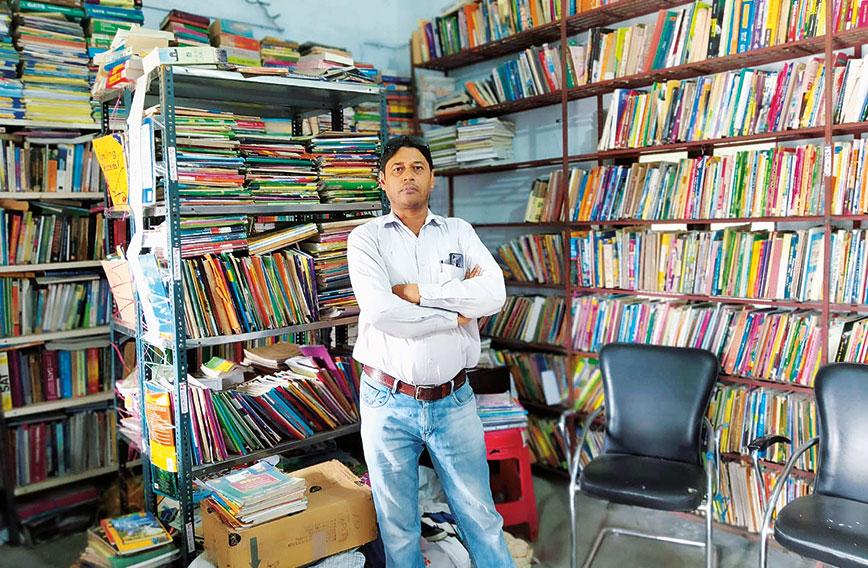

Arif Khan at a book bank in Dehradun

Textbook solution at book bank

Rakesh Agrawal, Dehradun

HOLDING a piece of white paper in her left hand and clutching her 10-year-old daughter’s thin wrist with the other, Urmila Semwal, a vegetable vendor, went to a bookshop in Dehradun’s popular Paltan Bazaar to buy textbooks. Her daughter, Kamla, had just secured admission into Class 6 in the local government senior secondary school. Urmila was looking for inexpensive NCERT textbooks for maths and science.

She got a rude shock when the shopkeeper handed her an entire set of books, by a private publisher, of all the subjects and told her she would have to buy the whole lot. Urmila couldn’t afford it. She left the shop without the textbooks for her child, feeling despondent and close to tears.

She told her friend, Salma Khan, who plies a vegetable thela (push cart) in the city, about her problem. Salma had a solution. She told Urmila about a book bank in Kaulagarh, a residential colony nearby, from where she had got second-hand books for her son, who was studying in Class 7.

Without delay, Urmila went there and returned elated, carrying the books. “With these NCERT books, Kamla will now pucca become a good student,” she beamed.

This useful book bank is being run by the National Association for Students’ and Parents’ Rights (NASPR), a Dehradun-based NGO, working to safeguard the rights of students and parents.

“In March 2018 I saw a video of a poor father in Kotdwar, a town about 120 km away in Pauri district, trying to buy four books for his son. The shopkeeper forced him to buy the entire pack. The video went viral. I saw it and I thought, I must do something about this,” says Arif Khan, who is president of NASPR.

He started a book bank with just four books and a table in Dehradun’s Nehru Colony. “I did it so that poor and deprived parents could borrow and exchange books. It would also save the environment as less paper will be needed, so fewer trees will be cut. We also fought with the schools. We insisted that schools must recommend NCERT books. Those books last for four to five years and can be easily shared,” says Khan.

From that one book bank where books were shared between four students, NASPR now has 14 book banks with tens of thousands of books. It has a repository of not just school textbooks but books for a range of competitive examinations, literary works, fiction, religious and mythological books. Ten book banks are in Dehradun, one in Guwahati and one in Kumarpada in Kamrup district, Assam.

Thousands of low-income parents have used these book banks to access books for their schoolgoing children. Many young adults have cleared tough competitive examinations, thanks to the books they borrowed from the book banks.

Mahesh Varma, son of an auto driver, is one such student. His father couldn’t afford to buy him books for the science stream. Mahesh loved studying physics and chemistry and he aspired to become a scientist. “Then, I heard about the book bank in our locality. I borrowed all my essential books from it and I stood 11th in class and then 12th in the next class, “bahut acche numbero ke saath" (with very good grades), he says. He dutifully returned the borrowed books after he finished studying.

Says Sudesh Uniyal, who is general secretary of NASPR: “The problem we faced was that sometimes people would not return the books. So we thought of a strategy. All borrowers must deposit 50 percent of the price of the books. Parents who are categorized as below poverty line or those who simply want to exchange books are exempt from this rule. Borrowers are now returning books.”

As word spread, people began donating used books to the book banks. When a three-day book fair was held in May 2019, many individuals, groups and NGOs donated books, school bags and uniforms to NASPR’s book banks. Amanu Tripathi of Astitva Women and Child Welfare Trust says they donated since they know the book banks are very convenient for poor and deprived students. “Doon Global International School in Harbartpur gave us about 1,000 books in 2017. The Neetu Lohia Foundation gave us 500 books in 2021,” says Deepchand Varma, national secretary, NASPR.

Using such books, many aspiring students, after passing their school exams, have also passed competitive examinations and now have a promising future to look forward to.

Twenty-three-year-old Ramesh Valia’s father is an auto driver. Two years ago he passed the chartered accountancy exam and he is now all set to join a major company in Delhi on a salary his father couldn’t have dreamed of. Pradeep Kashyap, son of a small-time farmer, passed the banking recruitment test last year and is now working in a nationalized bank. And Abrar Ali, who operates a couple of Vikrams — three-wheelers which run on diesel —says both his daughters are studying to join the IAS.

Apart from running book banks, NASPR’s mission is to ensure implementation of the Right To Education (RTE) Act and make sure that students, especially girls, are not harassed in any way.

“We found that private schools have employed many ineligible candidates as teachers. I pointed this out to S.P. Khali, additional director, elementary education, in the Department of Education, Uttarakhand. He took note and has promised to take appropriate action,” says Khan.

NASPR also fights against unjust closure of schools. When the Ministry of Defence issued an order to stop admissions at all schools aided by the Defence Research and Development Organization (DRDO) in the country for this academic session, it meant DRDO schools would be shut. The principal of Central School, DRDO, in Dehradun meekly followed the order.

“We didn’t take it timidly. NASPR raised this matter with the manager of the school. He tried to justify it by citing losses. I pointed out that even if there are just 10 students, you can’t shut the school since it’s not a business but a social enterprise. I have lodged a petition in the Uttarakhand High Court against such closure," says Khan.

NASPR has also been working against sexual harassment of girl students. “The chairman of the Indian Academy, a premier private educational institute, was allegedly sexually exploiting three girl students. We intervened in September 2018. He was arrested and imprisoned for a year, but was released since after a year the parents of these students backed out,” says Khan. “Similarly, the swimming coach of Pestle Weeds, another premium private boarding school, was arrested as he sexually molested a girl student from Punjab in January 2019. The school management wanted to ‘settle’ the matter for `25 lakh!”

Government schools aren’t better off. In September 2017, Parvesh Kumar, a history teacher of Sardar Singh Rawat Inter College in Nainbag, close to Mussoorie, reportedly raped a 15-year-old girl student over several months. “We contacted the police and that teacher was immediately arrested under the POCSO Act and imprisoned,” says Khan.

During the COVID-19 lockdown, when all schools were shut and children were confined to their homes, there were no bookshops or libraries to go to. “We converted our car into a mobile book bank in May 2020 and we went all over Dehradun, supplying books. We got requests not just from the city, but also from nearby towns like Rishikesh and Haridwar, for books that we happily provided,” says Puja Garg, who works for NASPR.

“Even the police helped us,” says Kavita Khan, Arif’s wife. “They would stop us for breaking lockdown rules, but when we told them our mission, they permitted us to go ahead."

Their mobile book bank was noted by the media and Red FM, a popular FM channel, interviewed Khan in its morning programme, Ek Pahari Aisa Bhi, by Kavya, a popular radio jockey in Dehradun.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!