A banquet hall became a well-equipped ward for COVID patients

Doctors For You weigh in as COVID crisis team

Civil Society News, New Delhi

IT was the middle of June and the new coronavirus had been rampaging its way across cities. The National Capital Region (NCR) had begun experiencing the disease’s onslaught. Lockdowns hadn’t worked in the absence of adequate testing, isolating of patients and tracking of their contacts.

As the virus roamed free, it was estimated that Delhi would end up having 500,000 cases, which was then considered a huge number. There weren’t the oxygen-equipped hospital beds, ventilators, doctors and nurses to cope with such a rush of patients — if a worst-case scenario became reality and so many turned up for treatment.

The Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) state government in Delhi explored many options as it scrambled to get its act together. One of the options walked through the door of Delhi Health Minister Satyendar Jain’s office when Dr Ravikant Singh and Dr Rajat Jain of Doctors For You (DFY) arrived with an offer to supplement the capital’s healthcare system.

DFY is an NGO which turns up during disasters to help local public health systems cope with emergency loads. It was founded by Dr Ravikant (as he prefers to be known) when he was still in medical college in Mumbai in 2007. It was initially intended to drum up blood donors.

Over time it has come to be modelled on Doctors Without Borders, an international group of doctors who serve at great personal risk during crises. Dr Jain is currently the president of DFY.

In India and neighbouring countries, DFY has served during floods and earthquakes by providing doctors, nurses and medical supplies in times when medical services together with local administrations have collapsed. In the longer term, it also tries to improve public hospitals by training doctors and medical staff in better practices.

DFY was eager to help the Delhi government cope with its coronavirus load. It said it could set up additional facilities with beds and the doctors and nurses needed to treat infected patients who required isolation. It could also work within government institutions like the Lok Nayak Jayaprakash Hospital (LNJP) to strengthen the standards of care available by providing paramedical staff, protective gear for doctors and nurses and generally improving conditions in wards.

The Delhi government took DFY on board. Apart from supporting hospitals, DFY was given a banquet hall in front of LNJP Hospital to set up a 100-bed facility. What was essentially a marriage venue was to be made into a medical facility.

A seemingly magical transformation followed. DFY put in good quality hospital beds with oxygen. It also deployed doctors and nurses from its own list of volunteers. So impressive was the pace with which DFY made all this happen that the Delhi government decided to hand over the Commonwealth Games stadium to the NGO to create a facility with 500 beds. With similar intensity, DFY worked to turn the stadium into a makeshift hospital in less than a week.

DFY currently manages about 600 hospital beds in Delhi. It has spent some Rs 6 crore accessed from an array of donors. The big backers have been the HCL Foundation and ACT Grant. “They have been very supportive and largehearted donors,” says Dr Ravikant. With the situation improving and the marriage season coming up, the banquet hall with 100 beds has been closed. But Delhi’s response to the pandemic has been vastly reinforced and should the number of cases begin to rise once more, as is happening during the time of writing, the administration will be much better prepared to deal with the upsurge.

The collaboration in Delhi is an example of what governments can achieve if they draw on the skills, speed and enthusiasm of voluntary organizations like DFY, especially when lives are to be saved and time is short.

DFY provides more than doctors and nurses with the spirit to serve in difficult conditions. It has systems for quickly putting stable and dependable infrastructure in place. Having spent 13 years rushing to disaster zones it knows how to source money, qualified people and materials.

Importantly, DFY knows to deal with governments. Nimble and action oriented as it is in the field, it is equally adept at working its way through giant bureaucracies. However, in the AAP government in Delhi it found an administration that instantly realized the potential of a partnership.

“From the first time we met Satyendar Jain, the health minister, matters moved quickly. Then he became infected with the virus and Manish Sisodia, the deputy chief minister, took over. But there was never any hesitation or delay in taking decisions,” says Dr Ravikant.

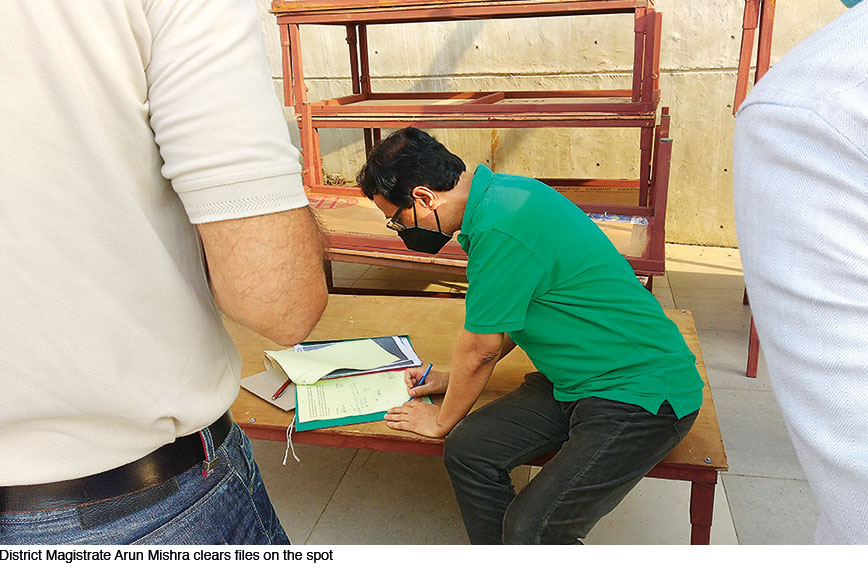

He recalls that the idea of turning the Commonwealth Games Stadium into a COVID-19 facility came from Sisodia himself. It was the perfect place for isolating patients, says Dr Ravikant, being secluded on the bank of the Yamuna and yet within the city. Changes took barely a week because the district magistrate of East Delhi, Arun Mishra, was always available and empowered to take decisions. On occasion, he would sign on files at the stadium itself.

Apart from Delhi, DFY also does COVID-19 programmes in Karnataka, Maharashtra, Kashmir, Punjab, Andhra Pradesh and Assam. Taken together, DFY says it has around 1,900 beds under its charge.

Dr Ravikant says DFY has about 100 doctors working at its COVID-19 facilities. It has a much longer list of some 450 doctors who have shown a willingness to serve in crises. Some prefer to remain in the cities and states where they are located and there are others who are ready to travel.

“When we call for volunteers we get as many as 1,000 responses. We choose from them. Over time we have put together a reliable list of doctors we know we can work with and depend on.”

There are specialists and general physicians. In a crisis, DFY looks for doctors who are located nearby. For instance, the doctors it wanted for Delhi were first those who were in the capital itself. Then came those in the NCR and neighbouring states like Haryana.

Asked if they work for free, Dr Ravikant says: “There is no such thing as free. Free does not work out because then there is no accountability. We pay everyone. An MBBS doctor gets Rs 1.5 lakh, keeping in mind that this is COVID-19 and high-risk. A qualified nurse gets Rs 50,000. We sign contracts for three months.”

Over time, DFY has learnt management. It has a permanent back office for accounts and human resources. Efficient management is important because going into a disaster zone requires preparation on multiple fronts. DFY also doesn’t tend to exit before six months. Doctors and nurses end up being stationed at challenging locations during that time and need to be looked after.

It is also important to get calculations right. Urgency has to come with method and it won’t do to rush people around without a clear plan. In Delhi, for instance, it was decided to have one doctor for 30 beds and one nurse for 15 beds. Since a rush was anticipated at the banquet hall facility outside LNJP, it was decided to keep some extra doctors there.

Now, one doctor for 30 beds really means four doctors because there are three shifts and the person on the night shift must take off the next day. Ditto for nurses. There is also the possibility of someone getting infected. All the nurses and doctors also need accommodation and meals.

DFY has acquired considerable expertise in materials management. What and how much to send where is a challenge that recurs from one assignment to the next. Time is invariably short and there has been a lot of learning in sourcing essentials reliably and without delay.

In Delhi, when 100 beds were needed, and orders were pouring in to small manufacturing units from all over the country, DFY had got its act together even while in talks with the Delhi government. It had identified half a dozen vendors and placed orders for 20 beds each with them.

In Karnataka, DFY’s partner has been the Azim Premji Foundation (APF), which wanted to help the state government cope with a rising tide of cases. A 150-bed facility called the Charak Hospital has been created.

“It is really quite amazing the speed with which DFY functions,” says Anand Swaminathan, who heads Azim Premji Philanthropic Initiatives. “They produce doctors and nursing staff from nowhere. It all just happens. DFY is also capable of pivoting quickly. It has a can-do spirit. We set out to do something with the state government that didn’t work out, but DFY didn’t have any problem adjusting and repositioning itself.“

Says Dileep Ranjekar, CEO of the Azim Premji Foundation: “Doctors For You brings in a strong network of young doctors and nurses who are ready to contribute to the COVID-19 healthcare efforts. It has been a valued partner of the foundation. In addition, the DFY team works in close collaboration with the authorities from government hospitals to ensure clear protocols of patient management.”

The pandemic has shown up multiple shortcomings in the public healthcare system. Poor reach, inefficient management and lack of motivation among doctors and nurses are some of the problems. Governments would do well to engage with voluntary organizations in healthcare to find solutions in real time and improve services. The private sector, with its focus on profits, doesn’t tend to provide viable answers.

Outfits like DFY score high on purposefulness, skills and the ability to innovate. The people who lead them inspire medical professionals to aspire to the higher and more social goals of the profession. When they work with government institutions they not only deliver better services but also enthuse government staff to perform with greater efficiency and dedication in the long term. What looked impossible begins to appear to be achievable.

DFY’s learning has come slowly and over time, the painful way. The successful turning around of a district hospital at Motihari in Bihar, for instance, took a year of handholding and engagement.

Dr Taru Jindal, a gynaecologist trained in Mumbai who camped in Motihari in Bihar during that period, remembers it as being a life-changing experience. She was working closely with the state government at the district level and improving the standards of a hospital which had only known neglect.

She says: “I find Doctors For You a highly successful model. It started so small, but these are doctors who wanted to do something for society and came together as a group. They realized that you have to set up an NGO and you have to learn management. First they started working in Bihar (during the floods), then in maternal and child health and now during the COVID pandemic. In the two years I have worked with them I have learnt that their hearts are in the right place and their capacity to work hard is limitless. I feel we need many, many more Doctors For You.”

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!