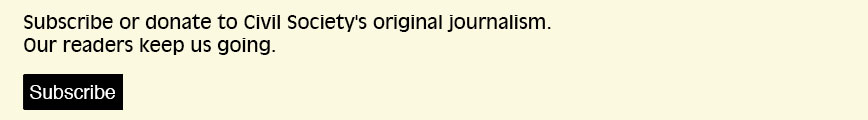

The micro hydel project at Taksang Gompa is at 12,000 feet in Tawang district. This is the power house. Note the dish antenna

Lights on the LAC: Micro hydel is the answer

Civil Society News, Gurugram

HIGH up in the mountains in Arunachal Pradesh, close to the border with China, villagers are experiencing for the first time in decades what it is like to have electricity in their homes at the flick of a switch.

Seventeen micro hydel projects, built on perennial streams, have been making it possible for them to have lights and watch TV and, as telecom connectivity arrives, charge their phones.

Home Minister Amit Shah in April inaugurated nine of the projects which had completed the mandatory trials and gone into commercial production with a capacity of 725 kW. But in all 17 are running and finally there will be 50 projects generating power in these remote parts near the border.

Micro hydel power is an essential element of the BJP government’s Vibrant Villages Programme. Roads have been built and other issues of access to services addressed. But the missing link in all such efforts has been electricity. No amount of development would be complete if villages continued to be in darkness.

So distant are these villages that taking the national grid to them is costly, logistically challenging and time-consuming. Some of them have just a few households. At the same time, enlivening these villages is important so that there is habitation on the border. Currently, there is migration, since people feel cut off, which needs to stop.

China has been pursuing a policy of developing villages on its side of the Line of Actual Control (LAC). Arunachal’s villages, by contrast, have been subjected to decades of neglect until the Modi government went into mission mode to build infrastructure. There is actually no time to be lost.

When it comes to taking electricity to them, micro hydel projects with localized grids are seen as the solution. They have small ecological footprints, do not require much capital expenditure and can be quickly installed. They are also easy to maintain and local people can be trained to keep them up and running. Solar is not an option because of heavy rain and cloudy weather for several months in the year.

Prashant Lokhande at a facility in Tawang district with two students who worked on the project there.

Prashant Lokhande at a facility in Tawang district with two students who worked on the project there.

Apart from meeting the needs of villagers and making their lives more complete and cheerful, these facilities also supply power to India’s forces on the border. They have so far been running diesel generators, which are both costly and polluting.

FIRST PROJECT

While the projects are currently being set up in mission mode at great speed, the Arunachal state government has for some time been working on using micro hydel power as a means of lighting up its remote villages. As early as in 2005, the then Deputy Commissioner of Lohit district, Prashant Lokhande, set up a tiny hydel unit with a capacity of just 10 kW at Kaho, which is the remotest village on the India-China border. It is still producing power.

Civil Society featured Lokhande in 2008, recording his pathbreaking achievement. Lokhande continued to serve almost continuously in Arunachal, apart from three years which he spent in the Indian embassy in Beijing. He has been instrumental in shaping the micro hydel strategy of the state government. Lokhande, 48, is now posted as joint secretary in the Union home ministry.

Much progress has been made from the first little plant at Kaho to the inauguration of the nine hydel plants by the home minister. They will operate across eight districts and meet the needs of 25 villages with a population of 5,332 people, apart from providing power to 11 Army establishments on the international border.

The Kaho effort was an outlier in 2005. The village is close to Tibet. It was off the grid and difficult to get to as well, even for an idealistic officer like Lokhande. Setting up the micro hydel project meant carrying equipment across a footbridge. He involved the local community and the plant came up with an investment of just a few lakhs of rupees. It was micro in every way but changed the lives of the local people. It was their Swades moment.

Last year, however, the state government launched a border village illumination programme to mark 50 years of Arunachal. Lokhande, now more senior in the government, led this initiative. What had begun at Kaho now became a structured effort with a dedicated budget of Rs 200 crore and timelines. A goal was set of 50 micro hydel units with capacities ranging from 10 to 100 kW.

Last year, however, the state government launched a border village illumination programme to mark 50 years of Arunachal. Lokhande, now more senior in the government, led this initiative. What had begun at Kaho now became a structured effort with a dedicated budget of Rs 200 crore and timelines. A goal was set of 50 micro hydel units with capacities ranging from 10 to 100 kW.

The focus has paid off. It is no mean achievement that so many projects in remote locations and difficult terrain have been commissioned in barely a year. All of them are being built by the state government’s department of hydropower. The planning and execution are being done by the state’s engineers led by Chief Engineers Jummar Kamdak and Along Ketan and Superintendent Engineer Motto Basar. Project reports go for vetting to IIT Roorkee.

To speed up projects, the state government has also been setting up the local transmission grids. It is quicker and finally more stable than being part of the national grid.

The first 17 projects have come up at a cost of Rs 50 crore and together generate 1,255 kW. Interestingly, the state government has already earned Rs 4 lakh of carbon credits through generating clean power.

GOING BACK

Lokhande recalls that he went back to the first project at Kaho and found it to be working perfectly well. “I was surprised to see that even after 18 years that machine was fine and providing power. We had, back then, trained two youngsters from the village to operate it and that system actually worked for two decades at hardly any cost,” he says.

Lokhande says micro hydel projects aren’t new to Arunachal. They had been put up in the past and connected to the grid. But problems of grid stability would follow. After visiting Kaho and seeing its continuing success, the idea of having a mission for micro hydel projects alone struck him.

Lokhande says micro hydel projects aren’t new to Arunachal. They had been put up in the past and connected to the grid. But problems of grid stability would follow. After visiting Kaho and seeing its continuing success, the idea of having a mission for micro hydel projects alone struck him.

“We could have many more micro hydels which would serve the dual use of villages and the armed forces. It would take us many years to take the grid to remote villages and it would be unstable because it would undertake a torturous journey through the mountains. Standalone local grid micro hydel would be better suited,” he says.

So, he discussed his idea with the chief minister and the deputy chief minister, who is also the power minister, and they came up with the Golden Jubilee Border Village Illumination Programme. It was launched in April last year.

|

|

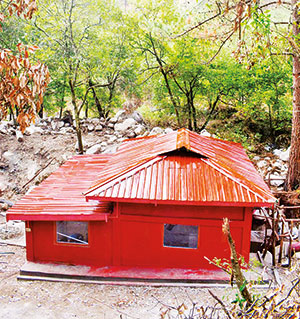

At Dichu, in Anjaw district, a few hundred metres from the LAC: The small power house with local grid, channel for diverting water and the turbine |

“The Kaho project generates only 10 kW but it was okay in those years for the village because it was unconnected by road. They had no power and it was important value addition for them. It cost us just Rs 2 lakh which we got from the MPLADS fund of Tapir Gao, the MP from Arunachal,” explains Lokhande. “The villagers were able to use the power for their basic needs and for TV. I provided DTH to the people. Kaho has just seven to eight households.”

Arunachal’s chief minister, Pema Khandu, says that the Union home minister’s visit to inaugurate the micro hydel plants shows the commitment of the government at the highest levels. But the state-level officers and engineers deserve special credit.

“I appreciate the hard work put in by our hydropower department and Prashant Lokhande who initiated this innovative and challenging project,” says Khandu. Chowna Mein, the deputy chief minister, adds: “I congratulate Prashant Lokhande, our former commissioner, for conceptualizing this programme and our engineers for executing it in mission mode.”

While the current urgency could well be for strategic reasons, the setting up of micro hydel facilities is in multiple ways an example of effective development. It is eco-friendly, economical, locally managed and transformational. It is a lesson on how to reach out to the underserved.

Lokhande says, of the villages that are being reached, “600 have a population of 50 and 90 percent have a population of less than 250”.

Stemming migration from these small villages is important. “We are of the considered opinion that civilians, doing cultivation in the border areas, who say, I’m an Indian, are the sentinels of border areas. They are the ones who protect our border,” he says.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!