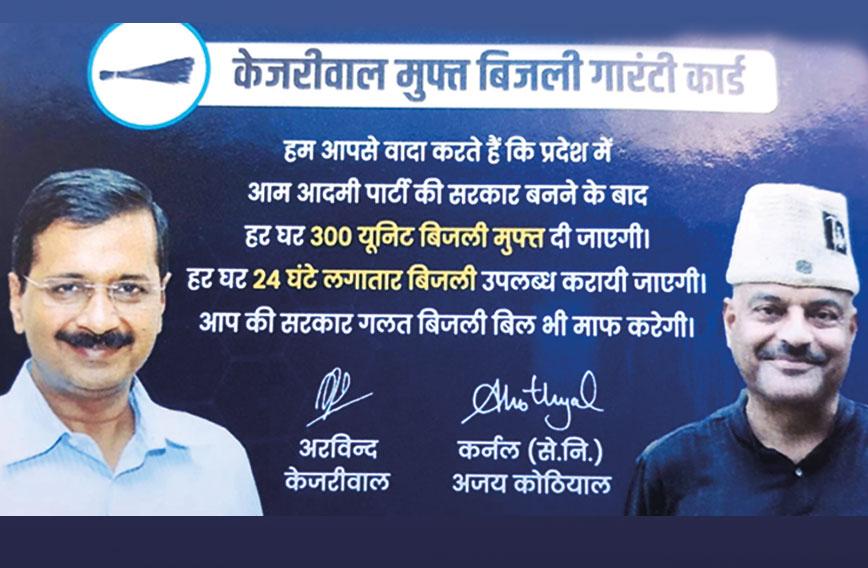

Has the free power poll promise gone too far?

Civil Society News, New Delhi

FREEBIES have been in the news. Political parties outdo one another in offering concessions to voters. High on the list of promises has been free electricity.

Leading the way has been the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), which has highlighted among its successes the 300 units of electricity a month it has been giving free in Delhi.

Free power, however, has decades-old precedents. Farmers have been getting free power across states. And in Punjab, much before AAP’s recent victory, free power was being given not just to farmers but also to urban and industrial consumers.

The bills have been adding up. Huge sums are owed to distributors and power producers across the country. Power sector reforms were meant to usher in accountability and rational practices. The architecture envisaged was of regulator, consumer, distributor and producer being in a synchronous arrangement. Political largesse to voters disturbs such an alignment.

Generous subsidies and non-paying consumers come in the way of having rational tariffs, regular investments in infrastructure and ultimately better quality of service.

Also, when they get power free, consumers tend to not opt for other more forward looking subsidies such as for solar power.

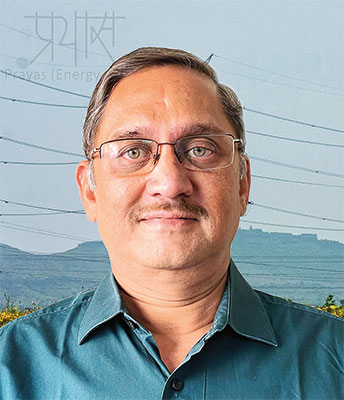

“Under the Electricity Act, a state government is at liberty to give concessions or free power as long as it compensates the distribution companies,” says Shantanu Dixit, a founding member of the Energy Group of Prayas, a Pune-based NGO which seeks to protect public interest and empower the disadvantaged.

“Unfortunately, there are many instances where the subsidy that needs to be transferred by the state government to the distribution companies is not transferred on time. Punjab is a classic case, and so is Tamil Nadu,” says Dixit.

Since the distributor has to remain financially viable to provide the standard of service stipulated by the regulator, not being paid on time has a cascading effect.

“Free power or the sponsoring of free power did not start with Delhi. It has been longstanding in the agricultural sector,” explains Ann Josey, a Prayas Fellow whose work relates to policy, regulation and the financial viability of distributors.

“With free power, a culture sets in where expecting payment for the electricity consumed becomes challenging. So does metering,” she says. “The distribution companies then have a structural disincentive to supply to these consumers because, on the one hand, there is no monitoring of the quality of service provided and, on the other, there is no revenue recovery from those consumers because money comes from the state government.”

becomes challenging. So does metering,” she says. “The distribution companies then have a structural disincentive to supply to these consumers because, on the one hand, there is no monitoring of the quality of service provided and, on the other, there is no revenue recovery from those consumers because money comes from the state government.”

“In agriculture we have seen this play out in very different ways across many states. In the domestic sector many of those challenges could be inherited,” she cautions.

Providing free power to urban consumers has the risk of rural supply being neglected even more than it is today because distribution companies are already cash-strapped and trying to balance many priorities. “Delhi is not new in providing free power in the domestic segment. Punjab has been giving free power of 200 units since 2008. They have that precedent before them,” points out Josey.

“In Punjab it started with BPL or below poverty line consumers. It was expanded to include anyone with an SC/ST caste certificate and then to all consumers. The ambit increased gradually with every passing election,” she adds.

Prayas, as an NGO, believes that professional knowledge, information and skills are needed to deal with the problems of disadvantaged sections of society.

Dixit, who is an electrical engineer and MBA, points out that subsidies are needed to help the very poor reap the benefits of electrification. The question is who should benefit and how much.

It makes sense to give 30 units free to the very poor and using that as a base recover the cost of supply through higher slabs. To give away 300 units, however, is to be generous with consumers who don’t need

the subsidy.

|

| Shantanu Dixit |

“In the past four or five years, state governments are stepping in and saying they will give higher concessions and compensate whatever tariff is determined by the commission,” explains Dixit, about how the situation has deteriorated.

“But it is crucial to have a debate and clarity about which consumers should be subsidized. People who consume 200 and 300 units aren’t the ones who need support because it means they are using appliances and can afford to pay,” says Dixit.

With rapidly increasing urbanization and the rising demand for power, it is important that there be clear goals. The shift to solar power, for instance, is an objective that needs to be met, but can get derailed.

“If you have free power or subsidy which is badly designed, it also compromises some of the other policy goals the government might have. For example, if you give 300 units of power per consumer, it’s very likely your rooftop solar initiative won’t pick up in the domestic segment because there is no incentive to set up a rooftop solar system or energy efficient measures,” says Josey.

Adds Dixit: “There are states like Punjab where even industries are being subsidized. Someone has to finally pay for this cost.”

The unpaid arrears of state governments relate not just to subsidies, but the bills of their own departments and services. They amount to Rs 1.4 lakh crore nationally. Interestingly, what state governments owe distributors is almost exactly what distributors owe producers.

Many gains have accrued from privatization of distribution. But Dixit points out that it is not just a question of ownership in distribution. All the stakeholders in the sector need to be accountable.

“The accountability of consumers is in facilitating correct metering, billing and paying bills on

|

| Ann Josey |

time. The state government should ensure that the subsidy is well targeted and that discoms are paid on time. Distribution companies need to be accountable for the quality of supply and efficiency of cost management and regulators need to oversee this. Just an ownership change won’t be sufficient,” he emphasizes.

Pointing out that “in the past five years the sector has undergone a sea change”, Dixit says that there is a need now to look for greater efficiencies — such as retail competition that allows the consumer to buy power from multiple sources.

“Here I am not suggesting tariff separation or allowing multiple distribution licensing in the same area because in our opinion those are highly complex mechanisms and I don’t think we have thought of the technical aspects and legal complexities which come from such models,” he clarifies.

But with technological changes the economics of the sector has changed. The cost of renewable energy like solar and wind has come down as have metering costs.

“As we deepen and broaden our retail competition and give choice to consumers who can have their own supplier based on an open access regime, the role of distribution companies will be limited to supplying really small consumers and maintaining wires. That should be our priority: how do we bring a competitive structure in place rather than focusing on transferring a public monopoly to a private monopoly,” Dixit elaborates.

The criticism of an open-access system is that it won’t be able to serve small consumers. But Dixit envisages a system in which a regulated rate system serves small consumers and those at higher levels of consumption avail of open access.

“To clarify, when I say competition in the retail sector, I am not saying every small consumer needs to have that choice. We need to look at techno-economic viability. We are saying over the next three to four years, all consumers who are above 20 KW load can economically move to a more competitive structure. Smaller consumers, those who are staying in apartments or jhuggi-jhopris, can very well continue with the distribution company as a regulated consumer base. It becomes the distributor’s job to supply power in a cost-effective manner at regulated rates fixed by the state regulatory commission,” he says.

Josey points out that currently distributors work on a cost-plus norm and over and above that they are ensured a 16 percent return on equity. There isn’t the incentive to strive for greater efficiencies under such norms. Anything regarded as a “prudent” cost is passed on to the consumer.

Says Josey: “If there is competition, the true cost of service can be brought out to some extent. Secondly, there has to be more stringent regulatory accountability and efficiency parameters should also be looked at.”

“Right now, the focus of regulatory commissions is to look at tariff and cost. There is hardly any focus on quality of service or supply. We are talking about a regulatory framework that can ensure efficiency. It’s not just about tariffs. We have tariff hearings but what about hearings for supply and service quality?”

Adds Dixit: “One of the recent moves by the central government under the green open access rules actually takes a step in this direction because they mandate that the reason for those rules is to lower the eligibility for open access to 100 KV and that will allow a lot more consumers to have their own supply, their own choices and contracts. So, there is already some move in this direction which is positive.”

The consumer will be able to get the power through the wires of the local distribution company. Then comes how much should be charged for the power, transmission and so on, for which Dixit says mechanisms are well established.

Under the Electricity Act, since 2003 any consumer as per defined thresholds of consumption can sign a contract with any supplier of power.

“The only thing that is changing is eligibility. It used to be 1 MW, and now it is going to be 100 KW, and maybe in another few years it will become 20 KW. The ambit of consumers who can avail of such choice is increasing. The framework remains the same,” he says.

The idea should be to bring in relatively smaller consumers so that the competitiveness and efficiency that the model provides benefits the system in a significant way.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!