Villagers of Jana at an SHG meeting

How Jana chose traditional farming

Bibhubanta Barad, Parijat Ghosh and Dibyendu Chaudhuri, New Delhi

On a sunny morning in the summer of 2017, a women’s Self-Help Group (SHG) at Jana, a village in the Gumla district of Jharkhand, congregated beneath a tamarind tree, their usual meeting place. They were discussing loans to be given to members to buy chemical fertilizers and hybrid seeds. Since costs of these inputs were high, members needed loans.

A few elderly people in the village got up and shared their concerns. They were worried about the increasing use of hybrid seeds, chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Were the villagers getting overly influenced by advertisements put out by pesticide and seed companies, they wondered.

Pitu Bhagat, a middle-aged man, said with pride: “We now eat standardized food, not coarse millets and other traditional foods.”

But one of the elders retorted, “No, we now eat poisoned food which is ruining our health.”

Like other Adivasi villages in Jharkhand, Jana once had a rich traditional agriculture system. Farmers planted a variety of crops. They had seed storage mechanisms and regenerative agriculture practices. But with the growing emphasis on modern agriculture, traditional systems began getting replaced with inputs and practices recommended by seed and pesticide companies.

In such several villages the transition was complete. In Jana, however, the opposition put up by elders compelled the villagers to think about the benefits and downsides of new practices. A reversal seemed possible — particularly if the traditional methods could be seen as improving crop productivity, boosting incomes and being good for the health and environment.

Reversing trends

To help the villagers of Jana take the path to sustainable agriculture, PRADAN, in partnership with the Azim Premji University (APU), launched ‘Adaptive Skilling through Action Research (ASAR)’, a reskilling programme revolving around three principles:

1. A balance between individual prosperity and collective well being as agrarian livelihoods are predominantly based on common resources

2. Reduced dependency on the market for agricultural practices and inputs

3. Adapting new technologies through experimentation.

The villagers had replaced their traditional agricultural practices and indigenous seeds with so-called modern practices and hybrid seeds, hoping to increase their income. However, this change made them even more vulnerable and dependent on the market. Hybrid crops are generally more susceptible to climate change, pest attacks and involve higher production costs leading to fluctuating profits.

Many villagers admitted that soil quality had deteriorated, the food they grew wasn’t tasty or nutritious and the focus was on individual prosperity and not community well-being. In the past, agricultural practices in Jana, like many other Indian villages, involved collective action such as ploughing, seed sowing or weeding. Gradually, people started doing agriculture individually. They forgot the ethos of collectivity since modern agriculture and its outputs are based on ideas of competition and profit rather than cooperation and reciprocation.

Many villagers admitted that soil quality had deteriorated, the food they grew wasn’t tasty or nutritious and the focus was on individual prosperity and not community well-being. In the past, agricultural practices in Jana, like many other Indian villages, involved collective action such as ploughing, seed sowing or weeding. Gradually, people started doing agriculture individually. They forgot the ethos of collectivity since modern agriculture and its outputs are based on ideas of competition and profit rather than cooperation and reciprocation.

Impact and outcome

In the last two years, following the principles of ASAR, many exposure visits, meetings and video shows were arranged. At first, a small group of local villagers were mobilized around the ASAR principles and then this group mobilized other villagers.

For exposure, the villagers of Jana were taken to Mendha Lekha in Gadchiroli district of Maharashtra, to understand how this tribal village had come together to practice agriculture, take collective decisions and rejuvenate forests. Mendha Lekha was the first village in India to get community forest rights under the Forest Rights Act of 2006.

The village won the right to harvest bamboo from the forest in 2015. It has since become a model for its management of community forest rights and collective agriculture. In 2015, the gram sabha earned Rs 40 lakh from sale of bamboo alone.

Jana villagers also visited Kharika Mathani in Jhargram district of West Bengal, to assess its community-led enterprise. Helped by PRADAN, the people of Kharika Mathani switched to using indigenous seeds to grow black rice and aromatic brown rice. Since market prices for such rice is around Rs 100 per kg, agriculture became a profitable proposition for them.

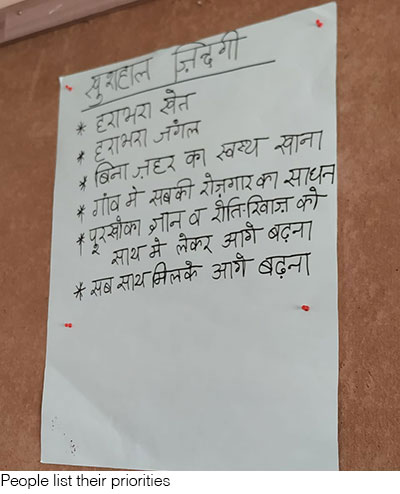

The visits were followed by brainstorming sessions. What were Jana’s aspirations for a Khushaal Zindagi? What were their needs? A baseline survey was carried out. Villagers were helped to form a core group and hold regular meetings.

There were regular interactions between the group of researchers and other villagers and decisions were taken based on ASAR principles. There were educative and brainstorming meetings as well as with members from every household along with video shows, presentations, group activities, debates etc.

This intense engagement for the last two years led to a change in mindset among the villagers of Jana.

They reduced their use of inorganic fertilizer and replaced it with organic fertilizer. When ASAR researchers explained the natural cycle of carbon and nitrogen to the villagers and how the application of chemical fertilizers and pesticides hampered this natural cycle, a reverse trend began. Application of chemical fertilizers declined from over 40 households to just around 15.

Hybrid seeds too began being replaced by local seeds. Using hybrid seeds trapped the farmers - they became dependent on the market for seeds; they were bound to use inorganic fertilizer; they became more vulnerable as the performance of these varieties is unpredictable in a situation of erratic rainfall, pest attack and temperature fluctuation due to climate change. Use of hybrid seeds has now declined to just 3.8 acres. Villagers are using desi varieties on 39 acres and improved varieties on 20 acres.

Jana villagers also began making more mindful choices. They opted for sanitary-wells instead of bore-wells. A sanitary-well is similar to an open-well but it is properly constructed and well protected from contamination, ensuring supply of safe water. The villagers discussed the need to monitor groundwater through open-wells by observing the water table, especially in summer. They rejected installation of bore-wells since water is pumped out injudiciously leading to depletion of groundwater.

The villagers became more open to experimentation. Their attitude to adopting new methods and technology became more positive. A group of farmers have started taking an interest in experimenting with different methods of cultivation, for example, seed conservation, composting and pest management. They began keeping data, analyzing the pros and cons of each practice and adapting as per their context.

Villagers identified ignorance as one of the reasons why the younger generation did not take an interest in protecting the forest. A group of people has prepared an ethno- medicine book and a biodiversity register. Hirasandh, a middle-aged farmer, says, “We will now protect our jungles and conserve our environment. We will also spread knowledge and turn our village into a model.”

The visit to Mendha Lekha, followed by brainstorming meetings, helped the people of Jana village understand the philosophy and importance of thinking collectively. They are now rebuilding a cohesive village community through mutual support by ploughing, weeding or harvesting together.

Jana was following the trend of most other villages in India where farmers have shifted to modern agriculture characterized by use of hybrid seeds and chemicals. However, within a span of two years of engagement with alternative thoughts, Jana is now showing the way with collective thinking and action towards more sustainable practices.

Comments

-

Rikky - Jan. 15, 2022, 8:31 p.m.

One wonders why sustainable work does not spread in other villagers in the locality? PRADAN is also working across states like Odisha, Bihar, West Bengal & Chhattisgarh. One wonders why PRADAN itself is not scaling these initiatives? PRADAN is promoting hybrid seeds & chemical based cultivation in states like Bihar, Chhattisgarh and Odisha for higher production. We need to think of scalability of these efforts.

-

Porus Dadabhoy - Aug. 6, 2020, 8:17 p.m.

India needs more agricutural programs and graduates , same for Veternary Sciences.

-

Mallika Sarabhai - Aug. 5, 2020, 6:09 p.m.

This collective thinking for the collective good is what is needed in all walks of life. Wanting to be the best at the cost of the common good is a capitalist ploy to get us into becoming consumers alone instead of human beings

-

Asutosh Satpathy - Aug. 2, 2020, 11:49 p.m.

A well intended effort .Signs of change visible.Hope we all will take it forward in other villages too.

-

Bandana Mandal - Aug. 2, 2020, 10:15 p.m.

Well researched. Nice article.