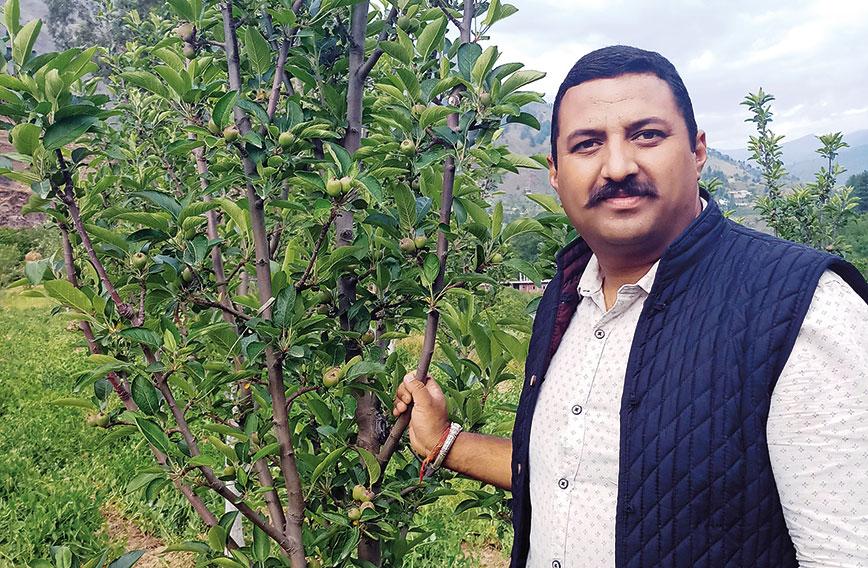

Lokinder Singh Bisht at his apple orchard

Can Himachal apples survive the big fall?

Raj Machhan, Shimla

Five years ago young apple growers, many of whom had given up jobs to return to family orchards, came together and formed the Progressive Growers’ Association (PGA) to improve the quality of apples produced in Himachal Pradesh through the use of better agricultural practices and robust saplings.

They were all poised to reap the benefits of these innovations when the coronavirus pandemic laid low their hopes. Export possibilities have all but dried up and to compound their problems Nepali labourers, on whom the apple growers depend, have gone back to Nepal.

A pall of gloom now hangs over the Rs. 3,000-crore apple growing business, a key source of farm incomes in Himachal Pradesh, particularly in the districts of Shimla, Kullu and Kinnaur.

Growers and members of the PGA are worried about what’s in store for them. But they also believe that the foundations they have created for a more modern and competitive apple industry will finally pay off when some normalcy returns.

The PGA mostly comprises young, like-minded individuals open to change and willing to try out new and better ways of planting, maintenance, harvesting, and marketing of apples.

Lokinder Singh Bisht, president of PGA, says, “We now have a membership of over 250 medium and large apple growers.” Over 70 percent of members left jobs in the corporate world to dedicate themselves full-time to horticulture.

“It made sense. The returns were more than what most of us were earning and the job is like a dream. Living close to nature and growing apples — what else does one want?” remarks Ashutosh Chauhan.

The PGA has set up a seven-member executive body to look after its day to day affairs. Major decisions involving investments and strategies are taken at an open general house where all members are invited. The members pay a one-time entry fee of Rs. 10,000, which goes into forming a corpus to sustain day to day activities.

The PGA has been changing the dynamics of growing apples. Thus far, apple varieties in Himachal have been dominated by the Royal Delicious type, which are big trees that take 12 to 15 years to come to fruition. The present seedling method of planting trees is giving way to the root stock method, which takes three to five years for fruit bearing and the trees are resistant to diseases.

A top priority of the PGA is to introduce new, superior quality varieties, which could compete in international markets. “We have been looking at advanced apple growing countries in Europe and to the US for new varieties,” says Bisht.

Members pool in money to travel to Europe and the US to source new varieties such as Scarlett, King Rot, Dark Baron Gala, Devil Gala, Memamescar, Granny Smith, and Gold Chief, among others. The group has been importing these varieties along with knowhow on acclimatizing them for plantation in Shimla, Kullu and Kinnaur.

The PGA regularly organizes seminars and workshops with foreign experts as key speakers, funded largely through their own collections and sponsorships from corporates of late. “The key takeaway from these meetings is the sharing of experiences and knowhow so that growers can successfully plant such varieties in their own climatic settings,” says Ranvijay Singh, a member. The cooperative has signed MoUs with apple associates from Holland, Italy and the US. “We have been learning from them. Information on the latest technologies in disease management has been especially useful,” says Bisht.

Improving the quality of produce and packaging are key focus areas of the group. For export, colour and size of apples determine price. Elongated apples, developed with standardized nutrients, fetch a premium in international markets.

“A 10-kg box of high quality apples sells for between Rs. 1,400 to Rs. 2,000, whereas a 28-kg box of our prevalent qualities fetches between Rs. 1,400 and Rs. 3,000,” says Bisht. The group recently introduced a five-kg pack for high quality apples, which can be given as gifts during festivals and corporate events.

The PGA has set up an outlet of their own at Kharapathar, around 80 km from Shimla, to sell cartons, insecticides, pesticides, packaging material, and tools used in orchards. Since they buy in bulk, they sell these products at a price lower than market prices, making a small profit at the same time.

Remarkably, the PGA has not involved the state government in most of its activities. “It becomes too cumbersome. We do avail of subsidies but our policy is not to overly involve government departments. They take too much time,” said a member.

The PGA plans to set up cold storages and processing units to buttress its marketing chain. “Though we will be tapping financial institutions for funds, we are trying to raise most of it from our group,” said Karan Chauhan. It is also working to do away with the cartel of commission agents who usually cream away most of the profits.

The PGA has also plugged into a Rs. 1,200-crore World Bank project for enhancing post-harvesting techniques. “We cannot compete internationally right now, but we are moving towards it. At present only 10 to 20 percent of our total produce is of high quality. We plan to increase that to 50 to 60 percent. Along with standardization of grading and adaptation of universal cartons we are sure our B and C quality apples too will fetch a much higher price,” says Bisht.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has cost us dearly. We have been hit on multiple fronts,” said Ashutosh Chauhan, who is from Shimla’s Rantnari belt. Orchard owners in the state’s apple bowl are heavily dependent on Nepali labour, whose physique is uniquely suited to the tough mountainous terrain of an apple orchard. Nepalis are adept at horticulture operations such as preparing plant beds, spraying of insecticides, pruning, digging the soil and so on.

Over the years, the Nepalis have integrated with the local people, and become almost extensions of native family units. Some Nepali families have settled in the hills. They live in their own temporary houses, their children attend local government schools, and they till the land, growing vegetables and other cash crops provided by orchard owners. It is a unique symbiosis that has thrived over the years.

Every October, most Nepali workers travel to Nepal to visit their villages. They usually return with a large posse of temporary labour who work from May to June and do all the groundwork for the upcoming apple season.

But this year the Nepali worker is nowhere to be seen. Orchard owners are in touch with their usual groups of labour on mobile phones, but so far the chances of them returning appear bleak due to the sealing of the Indo-Nepal border and imposition of curfew in Indian states.

“We are ready to come, but we are not allowed to cross over to India. There is even talk of visa requirement for those who want to come. Our families are in the grip of a fear psychosis and the general outlook is that staying put in our villages is the best strategy for the time being,” said Ram Bahadur, a resident of Salian district.

Perhaps a precursor of things to come is the fate of early ripening fruits such as plums and other local vegetables grown in upper Himachal. Due to lack of labour and marketing, plums rotted on the trees and there is no demand for vegetables such as peas. Cauliflower is selling for Rs. 5 per kg in Rohru, and a half-kg box of cherries is selling for an all-time low of Rs. 30. Elsewhere, in places like Theog, the vegetable belt of the state, the produce is virtually rotting in the fields.

Dr K.C. Azad, former director of Himachal’s Department of Horticulture, says, “Due to shortage of labour we are expecting as much as 50 percent of the apple crop to remain unplucked. There is going to be a huge amount of wastage.”

Growers are also concerned about the non-availability of apple packing trays which are manufactured in plants located in the border industrial belts of Baddi and Parwanoo. “The production of trays started four months prior to the onset of the apple season in early to mid-July. But so far, we have not received any raw materials for them,” said a manufacturer.

Dr Rajender Jhobta, a surgeon and a keen horticulturist, says, “This year has been one of the worst in history. We were in any case expecting a 50 to 60 percent drop in production. In addition we are now facing problems on all fronts — labour, transportation and packaging.”

As a way out, Jhobta suggests the government encourage big business houses such as Adani, Reliance, Big Basket and Mother Dairy to directly source crops from farmers and sell at their outlets across the country. “But that too will depend on whether there is a demand for apples given the overall downturn in the economy,” he said.

Comments

-

RAKESH MACHHAN - June 12, 2020, 6:09 p.m.

Suggest remedies to tackle such problems, concrete advices must be shared with everyone. Anyway analysis is very informative.

-

Kailash Manta - June 3, 2020, 1:16 p.m.

Dr. Jobta's suggestion is good. My suggestion is that instead of packaging materials we should go for useing plastic crate like plucking, carrying, transporting to various mandis of India

-

Jitender Chauhan - June 1, 2020, 10:41 p.m.

PGA association does a remarkable job through social media and gives wonderful tips to apple farmers regarding nutrition management, pruning tips and soil management.

-

Pradeep - June 1, 2020, 3:30 p.m.

Nice Bhai ji