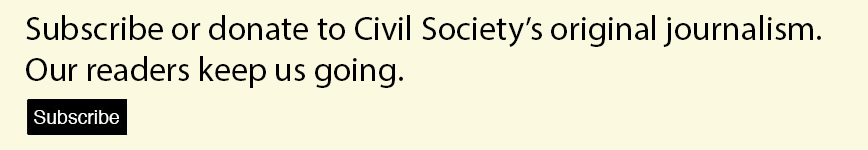

Harvesting bananas is an occasion marked with family and friends

Banana bank’s rare varieties go commercial

Shree Padre, Kasaragod

DURING the pandemic, Babu Parambath, a social activist, mulled growing something on his sister’s tiny 0.20 acres of land lying idle before his eyes. He'd been extolling the virtues of organic farming to all and sundry but the truth was, he’d never picked up a spade.

DURING the pandemic, Babu Parambath, a social activist, mulled growing something on his sister’s tiny 0.20 acres of land lying idle before his eyes. He'd been extolling the virtues of organic farming to all and sundry but the truth was, he’d never picked up a spade.

Parambath began growing new varieties of banana on that land. In the process, he got more and more immersed in collecting new varieties. Within a year, he had amassed 112 varieties sourced from different areas. A few were very rare.

One day, it struck him: “If my sister wants the plot to construct a house, or for anything else, what will be the fate of my painstakingly collected banana varieties? A flood or natural calamity could also destroy this genetic wealth. How can I conserve it all here?”

An idea then dawned on him — a banana bank. He would give five banana suckers to local people keen to cultivate the fruit. This way, rare varieties would be retained in the area. If anyone were to lose a variety, he could procure it from the others. In the process, interest in banana cultivation and the culture of eating homegrown fruits would grow, he reasoned.

If you look closely at Babu Parambath’s one-year account of his 0.20 acre banana garden, you won’t believe your eyes. In 2022-23, he earned Rs 272,300. His expenses were just Rs 47,500. So, his net income, all profit, was Rs 224,800!

Growing bananas

The banana plays an important role in the Kerala diet. All parts of the plant are consumed. The problem is that Keralites are so fond of their Nendra banana that no other variety is of much interest to them.

That was Parambath’s first problem. Luckily, he had a ready audience willing to listen, because of his many welfare activities. He had networked resident welfare associations, an organic produce marketing cooperative, a group doing rainwater harvesting, and more.

He began telling them about his plan of starting a banana bank. During one such interaction, a young National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) officer listened keenly. Impressed, he asked Parambath to draw up a project proposal on the banana bank. NABARD studied his plans and gave him a grant of Rs 2.5 lakh for two years from 2022 to 2024, to start the banana bank.

|

| Babu Parambath with one of his banana varieties |

Parambath shortlisted 35 banana varieties for distribution to 100 houses. Since the response was enthusiastic, he expanded distribution to 200 houses spread over four clusters.

“Ours was not like any government project. We ensured that the plants were given only to interested persons,” he says.

“There were two objectives,” points out Mohammad Riyaz, district development manager, NABARD, for Malappuram and Kozhikode districts. “One was propagation and disseminating rare banana varieties to different farmers and second was conservation by ordinary farmers. Both objectives were fulfilled very nicely. All participating farmers are now getting very good returns.”

Distribution, marketing and sales seamlessly merged when Parambath decided to set up his banana bank under the aegis of the Niravu Farmers Producer Company Ltd.

Niravu, which means ‘full’ in Malayalam, started as a community initiative in 2006 in Vengeri under the Kozhikode City Corporation which had plans to promote organic farming. In 2017, Niravu floated a farmer-producer company called the Niravu Farmers Producer Company Ltd. The banana bank was ensconced there.

Thanks to media coverage people knew about Parambath’s banana collection and the rare varieties on offer. The number of farmers who approached the banana bank, perhaps 40 or 50, was small because this is an urban belt belonging to the corporation.

Most people keen on cultivating offbeat varieties were from different professions. They had small bits of land ranging from 2,100 square feet to 4,400 square feet. A few had never grown bananas. There were also families who had been cultivating one or two local banana varieties, but didn’t have access to rare ones.

Distribution of banana plants was only the first step. Ensuring that these families planted the banana varieties and took good care of them was more difficult.

The Niravu Banana Bank roped in the services of two agriculture science graduates, Athulya and Aswathi Narayanadas, from Kerala Agriculture University (KAU) to monitor cultivation. Along with Parambath, they visited all homesteads and kept guiding growers through a WhatsApp group.

“People who weren’t farmers were also very keen to grow bananas. Niravu guaranteed them a good price through their own network for banana bunches as well as plants. This helped spread banana cultivation and retained the interest of stakeholders,” says Athulya.

Devadasan P.K., a former army employee, was already interested in cultivating new banana varieties. His association with the banana bank fuelled his hobby. Now he has 80 varieties, some of which he procured from different sources in Kerala.

“The advantage we have is that the Niravu FPC’s sales counter gives us a good price for our banana bunches. Many banana farmers contact me for plants of rare varieties. Also, we don’t have to give the sales counter full banana bunches. We can just give hands too. When we harvest a new variety, we can keep one bunch for our use and sell the rest.”

Keen to cultivate diverse banana plants on their campus, Providence Women’s College in Malapparamb got deeply involved in the banana bank project. Initially, they had only five varieties. They acquired 44 varieties from the bank which they asked their students to plant.

“Now the college has about 100 varieties. Some have already produced bunches,” says Dr Jeena Karunakaran, a faculty member. “We, four or five lecturers, also took a few plants home. I had five varieties earlier, now I have 40. A few have yielded bananas.”

Dr Karunakaran favoured varieties like Manjeri Nendran, Chenkadali and Swarnamukhi Nendran. “When we buy the same variety from the market we find the banana is not as tasty as the one we have grown,” she observed.

Dr Minoo Divakaran, a professor of botany in the same college, has arranged for name plates for each banana plant with its own QR code. The code shows details of each variety when scanned. “We got the name and QR code printed on metal plates since they can’t be spoiled by rain. Many of our QR codes are connected to the varietal details given by the National Research Centre for Bananas (NRCB) website. Interested students make use of this information.”

“When Babu Parambath gets newer varieties, he gives one plant to us. That’s how we now have 100 varieties. Our dream is that sometime in the future our students will have all these varieties in their homesteads,” says Dr Divakaran.

Income and diversity

Although the two-year project of the Niravu Banana Bank is over, give and take of fruits and plants is continuing enthusiastically. The bank charges Rs 250 for each sucker of a special variety. “Our highest booking, of almost 2,050 suckers, is for the Zanzibar variety. In the normal course, this would take decades to deliver,” says Shilpa N.T., manager of Niravu FPC’s sales outlet.

The biggest problem that farmers face is that traders don’t buy new varieties for a higher price. They treat every variety on a par with the commercial one and pay the same price.

But the Niravu sales outlet gives growers a higher price. Even when the Nendran banana’s market price is Rs 70 per kg, Niravu pays Rs 100 per kg. The FPC has fixed prices depending on variety and quality. The farmer or cultivator has to just pay 13 percent of sales proceeds to the outlet as handling fee.

Each member has a code which is mentioned on the bill for producer traceability. Since the Niravu FPC pays more than the market price, many households are incentivized to grow newer varieties.

Babu Parambath’s impressive income from his small garden was possible because of four factors. One, the Niravu outlet bought special varieties of bananas for a high price. Being organically produced, the demand was good. Second, Parambath himself did most of the manual work, thus saving on labour costs. Third, since the bananas were rare varieties, the suckers of the mother plants attracted demand and were sold through the Niravu sales counter. Fourth, through a simple method called macro propagation, taught by the National Research Centre for Banana (NRCB) in Tiruchirappalli, Parambath produced and sold hundreds of macro plants too.

For growers of new banana varieties, it is not the fruits alone that bring in an income. Young plants or suckers too are in demand. Depending on the variety, each mother tree yields two to six suckers. The Niravu sales outlet accepts bookings for suckers as well as for fruits.

The outlet sells banana hands and bunches. A frontline rack exhibits the best varieties of banana hands with their respective names. Nowhere else do you see the names of bananas displayed.

“Farmers don’t need to bring the whole banana bunch to our shop. We buy the hands too. This is very convenient for people who want to cultivate a new variety. If customers have to buy the whole bunch, they won’t be able to consume it. It will get rotten,” says A.P. Sathyan, chairman of the Niravu Banana Bank.

Members of the bank also have access to training and the latest knowhow. Twenty-five members went on a study tour to KAU’s Banana Research Centre at Kannara in Thrissur. Subsequently, another 25 members went to the NRCB in Tiruchirappalli. The training they got in both places improved their skills and enthused them further.

The bank’s impact

The banana bank has succeeded in removing the average Keralite’s mental block against other varieties of banana. They have realized that the Nendran banana isn’t the sole custodian of taste and health.

Kerala now has about a dozen banana variety collectors. They have started selling suckers of rare varieties through social media. It has sparked huge interest and demand. The suckers are costly because sellers have spent a lot of money procuring the mother plants. It is not easy for ordinary people to acquire a rare variety.

Significantly, the bank has shown that local communities can conserve and sustain rare varieties. The banana bank offers rare planting materials that people would not have been able to access. It has also demonstrated that varietal conservation, even by planting a small batch of five rare varieties, can be remunerative, if grown organically and sold through a dedicated sales outlet.

Comments

-

ken love - Oct. 14, 2024, 1:32 a.m.

Another fantastic Story from Shree Padre. Thank you sir for being so vigilant in finding and reporting these inspiring stories.