SANJAYA BARU

A new ‘uncertainty complex’ is unsettling lives and has already reversed the gains of five years of human development at the global level, says the latest United Nations Human Development Report 2021-22. Published annually since 1990, the UNDP HDR has become the global conscience keeper, reminding policymakers and political leaders around the world that an increase in gross domestic product (GDP) is not the only or the most pertinent indicator of progress. Rather, human progress should be tracked by considering improvements in the educational and health status of individuals and nations and human well-being as a whole, of which income is just one important measure.

HDR 2021-22 defines what are called “three novel sources of uncertainty” as follows: (a) the Anthropocene’s dangerous planetary change and its interaction with human inequalities; (b) the purposeful if uncertain transition towards new ways of organizing industrial societies — purporting transformations similar to those in the transition from agricultural to industrial societies; and (c) the intensification of political and social polarization across and within countries, due in part to, the report says, “misperceptions both about information and across groups of people — facilitated by how new digital technologies are often being used”.

“Political polarization complicates matters,” says the UNDP report. “It has been on the rise, and uncertainty makes it worse and is worsened by it. Large numbers of people feel frustrated by and alienated from their political systems. In a reversal from just 10 years ago, democratic backsliding is now the prevailing trend across countries. This despite high support globally for democracy. Armed conflicts are also up, including outside so-called fragile contexts. For the first time ever, more than 100 million people are forcibly displaced, most of them within their own countries.”

HDR 2021-22 draws our attention to, among other issues, two post-COVID phenomena, namely, uncertainty and a reversal in human development. Economists have dealt with the problem of risk. However, measuring and understanding the impact of uncertainty on economic and social development remains a difficult task. In a book I edited last year, Beyond Covid’s Shadow: Mapping India’s Economic Resurgence (Rupa, 2021), I had an essay on “The Political Economy of Uncertainty”. I had referred to studies on the economic and social impact of the COVID-19 pandemic that drew attention to a massive spike in individual and social uncertainty about the future.

HDR 2021-22 echoes one of the conclusions of my essay, namely, that with increased uncertainty, individual economic expectations would be suitably moderated — impacting macro-economic outcomes. While governments around the world have been dealing with the consequences of such uncertainty, their hands have been weakened by a global economic slowdown that has followed, reducing their fiscal capacity to intervene productively in the economy. To add to this, the inflationary impact of post-COVID monetary easing kicked in just as the Ukraine war further pushed up commodity prices. The global economy has slid into stagflation.

All this has contributed to a reversal of human development indicators, and in 2021-22 the global HDI went down all the way back to where it was in 2017. Of course, all countries have not been uniformly impacted. China, for example, has been able to improve its HDI ranking despite the impact of COVID lockdowns, while India has in fact experienced a backslide over a longer period, beginning with 2017. For six long years, India’s HDI numbers have declined, pointing to reduced income levels, and reduced educational and health outcomes.

When India’s GDP overtook that of Britain, becoming the world’s fifth largest economy, this news hit the media headlines. However, when HDR 2021-22 showed a decline in India’s HDI numbers and rank, the media largely ignored the bad news. Economic and social progress are better measured by human development indicators rather than national income, especially when such income is highly skewed and becoming increasingly so.

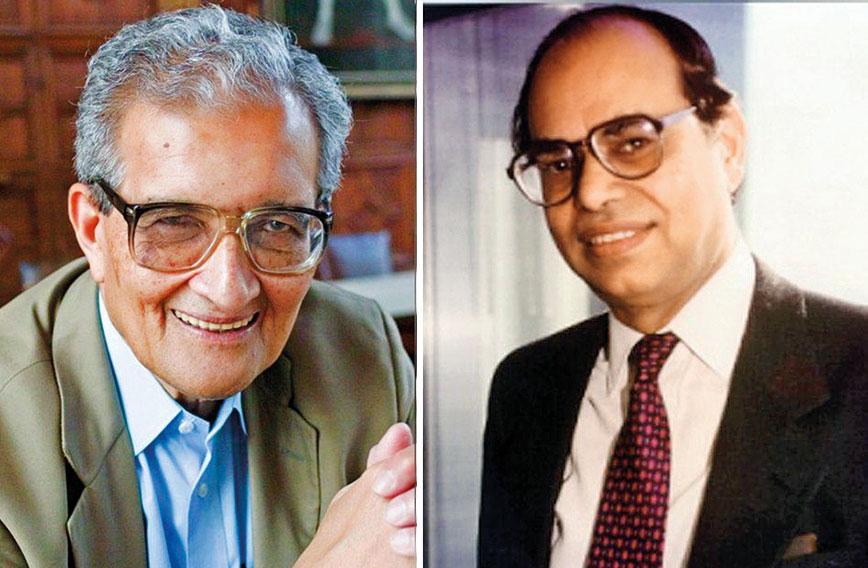

The international community owes the concept of human development and the idea of an index to two South Asian economists — Amartya Sen and Mahbub ul Haq. While Sen developed the concept of ‘human capability’, drawing attention to the need for public investment in education and health, that would turn human beings from being viewed as social liabilities into economic assets, Haq developed the human development index and produced the first HDR in 1990. The report boldly declared that “people are the real wealth of a nation” — echoing Telugu writer Gurajada Appa Rao’s famous slogan, “desamantey mattikadoi, desamantey manushuloi” (a nation is not defined by its territory but by its people.)

A contemporary of Manmohan Singh at Cambridge University, Haq was finance minister of Pakistan in two of Benazir Bhutto’s governments and went on to head the UNDP. It was just happenstance that I had moved from an academic position in Hyderabad to join the media in New Delhi in 1990 when Haq arrived in India to launch his first report. Few in the Delhi media took any interest in HDR at the time, but I formed a lifelong association with Haq, attending every single global HDR launch around the world and, in 1997, went on to act as a UNDP consultant evaluating the impact of HDR.

For 32 years the HDR has systematically drawn our attention to the challenge of human development. Between 1990 and 2016, for a quarter of a century, India consistently improved its index numbers and HDI rank. The slide in the numbers since 2017 and the fall in rank in 2020 and 2021 should send alarm bells ringing not just in New Delhi but across all state capitals. Health and education are the responsibilities of both the Centre and the states. In fact, the states bear a larger responsibility.

Many state governments had started publishing state-level annual HDRs, with Digvijay Singh pioneering the effort in the 1990s as chief minister of Madhya Pradesh. These reports tracked state-level changes in human development. HDR 2021-22 should revitalize this effort. The Centre and state governments should endeavour to improve India’s rank next year and every year thereafter.

Sanjaya Baru is a writer and Distinguished Fellow at the United Service Institution of India.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!