SANJAYA BARU

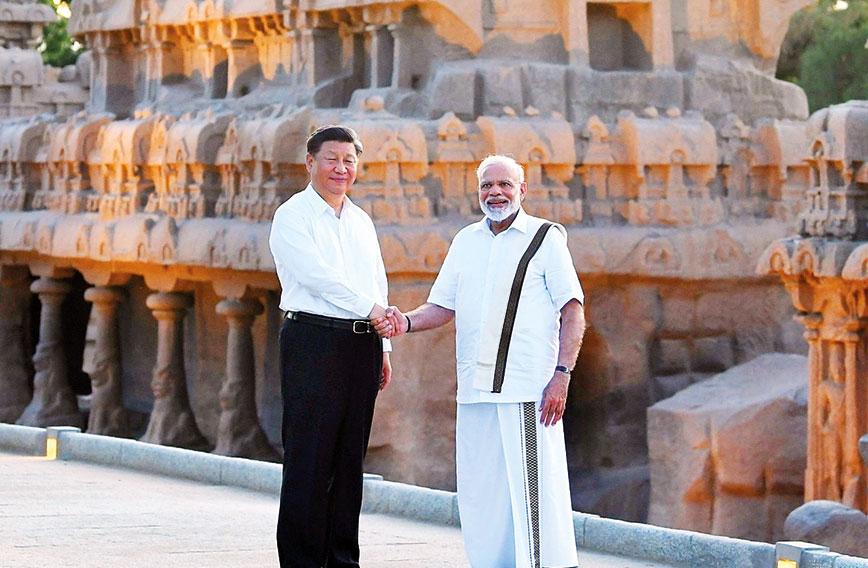

It is not surprising that the subject of India joining the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement figured in the talks between Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping. There has been considerable opposition to RCEP within the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) on the grounds that it would hurt Indian manufacturers. Even the head of the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh, (RSS), Mohan Bhagwat, signalled caution on the matter, flagging concerns raised by the RSS economics wing, the Swadeshi Jagran Manch (SJM) that has been resolutely opposed not just to RCEP but to free trade agreements (FTAs) in general.

Interestingly, this is one issue on which the BJP, RSS, the Communist Party of India (Marxist) and Sonia Gandhi have been on the same page. Both the BJP and the CPI(M) had criticised Prime Minister Manmohan Singh for entering into several FTAs during his tenure in office. The anti-FTA view received indirect support from Sonia when she wrote a letter, as Congress president, to Prime Minister Singh urging him to review the government’s decision to negotiate an FTA with the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN). Sonia echoed the view of many in the BJP and the CPI(M) that the Indian home market was large enough for the growth of Indian enterprise and that trade need not be viewed as an engine of growth. Rather, FTAs would threaten the interests of Indian producers.

The CPI(M) had specifically objected to the ASEAN-India FTA on the ground that it would hurt plantation growers in Kerala and West Bengal. Singh had to defend himself, telling a CPI(M) delegation led by Kerala’s finance minister, Thomas Isaac, and the then head of the Kerala State Planning Board, Prabhat Patnaik, that an FTA with ASEAN would also benefit the friendly communist republic of Vietnam!

In response to Sonia’s letter to the prime minister, Singh had said at the time, “Our approach to regional trade agreements in general and FTAs in particular has been evolved after careful consideration of our geopolitical as well as economic interests. Although India has a large domestic market, our experience with earlier relatively insular policies, as also global experience in this regard, clearly brings out the growth potential of trade and economic cooperation with the global economy.”

Prime Minister Modi can in fact quote his predecessor verbatim back to the naysayers on RCEP within his own party. The RCEP is not just a trade deal but also an entry point into the new Asian economic architecture that China is seeking to build. Having created the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and set up the Chiang Mai Initiative, as China-led Asian parallels to the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, Beijing is creating its own trading regime through RCEP, even though ASEAN sits in the driving seat. India is wary of RCEP because it could open the door wider to Chinese imports when the huge trade deficit it faces with both ASEAN and China is a problem it has been trying to resolve.

The Indian case is a strong one. India seeks an FTA not just for manufactured goods but also services and investment. India has also consistently fought for a freer regime for the movement of professionals through the so-called ‘Mode 4’ negotiations in the World Trade Organisation. After all, if the rules of globalisation enable free movement of goods and capital, why not free movement of skilled labour? It remains to be seen whether Modi’s conversation with Xi will have any impact on the final outcome in the RCEP negotiations.

What is surprising, though, is that despite murmurs against FTAs in general and RCEP in particular, the issue has not become a platform for wider political mobilisation. Recall the manner in which the Left and BJP opposition stirred up countrywide protests against India joining the WTO. Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao had to battle the combined opposition that included socialists like Mulayam Singh Yadav and Lalu Prasad Yadav in defending the infamous “Dunkel Draft”. Farmers marched in their thousands protesting against “Uncle Dunkel” — Arthur Dunkel — the European trade negotiator who had drafted the WTO agreement. It took all of Rao’s persuasive powers and Machiavellian skills to get the Indian Parliament to endorse India’s membership of the WTO at a time when he was still running a minority government.

That the RCEP agreement has not been a focal point for wider political mobilisation against the Union government is also a testimony to the distance Indian public opinion has travelled on the issue of foreign trade and its role in India’s development. Though, to be sure, the government has also protected itself by raising tariff walls and protecting sensitive sectors.

The direction of trade policy and the debate on RCEP draw attention to the fact that India continues to pay a price for not being able to establish a more competitive manufacturing sector. The solution to the problem lies at home and there is little that trade negotiators can do when so many other developing countries are willing to participate actively in the international division of labour. Three decades after India opened up to the world, the economy still remains relatively non-competitive, though it cannot be accused of being too insular given that foreign trade now accounts for half of India’s national income.

Going forward, India requires an integrated manufacturing, agricultural, horticultural and trade policy.Such an integrated policy cannot come out of a government that still functions within silos. Perhaps the prime minister should constitute a national trade policy authority under his chairmanship with a competent trade official like Hardeep Singh Puri who not only is given cabinet rank but has the power to deal with ministries that formulate domestic economic policies.

India has been a trading nation for centuries with a footprint across the Eurasian landmass and across the Indian Ocean region. To regain that status it needs a comprehensive external economic policy much like its external political and strategic policies that the Prime Minister’s Office and the External Affairs Ministry develop together. Manmohan Singh created a cabinet-level Trade and Economic Relations Committee (TERC) with that objective in mind. The time has come to give that committee a secretariat and a senior minister who can act as a helmsman.

Sanjaya Baru is a writer and Distinguished Fellow at the Institute for Defence Studies & Analysis in New Delhi

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!