SANJAYA BARU

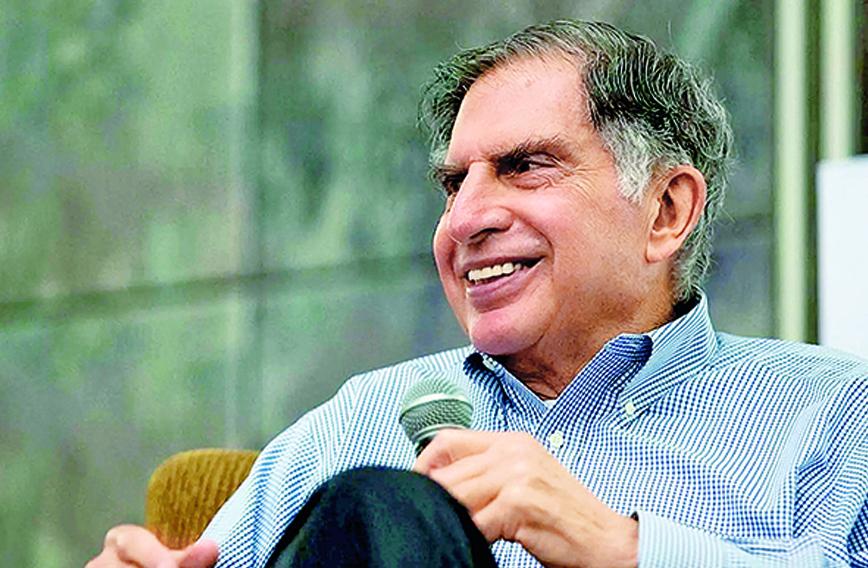

A running theme in the many tributes paid to industrialist Ratan Tata has been the recognition of his record as a philanthropist and his humane personality. Evidence normally cited of the former is the record of the Tata Trusts and of the latter is his care of stray dogs. Philanthropy is typically more institutional and the expression of social commitment. Charity or concern for the underdog, so to speak, is more personal and emotional. Ratan Tata was known for both. Indeed, the Tata Group has set a benchmark of sorts for the social commitment of Indian business.

It must be pointed out, though, that a philanthropist is not necessarily a charitable and humane individual. The philanthropy of most Indian businesses and businesspersons is nothing more than a means of tax avoidance or adherence to the provisions in company law relating to corporate social responsibility (CSR). Charity, on the other hand, is a more heartfelt response to social inequity and individual need. Ratan Tata expressed his social commitment both institutionally and personally.

Pushpa Sundar, formerly of the Indian Administrative Service (IAS), wrote a series of books, including Business and Community (SAGE, 2012) and Giving with a Thousand Hands (Oxford University Press, 2017), examining the track record of business philanthropy and the charity of the wealthy in India. Ratan Tata even wrote a foreword to the book that examined the record of CSR. Sundar’s general conclusion is that the track record of India’s wealthy as far as charity and philanthropy are concerned is abysmal.

One does not have to delve deep into social science research to discover this fact. Walk into any trendy market or drive through any metropolitan crossroads. The poor and the needy are before us. Often cooking, living, sleeping, playing on footpaths along busy streets. The attitude of the urban rich, especially the entitled nouveau riche, to the poor and the needy is a striking commentary on the social outlook of a prospering nation.

I make a distinction between ‘poor’ and ‘needy’, for often the needy are not necessarily poor. Merely disenfranchised by the market. Every time my daughter, Tanvika, and I go to New Delhi’s trendy Khan Market, she points to this difference. Shuklaji is an educated, visually impaired gentleman, an independent individual with a demeanour of dignity, who stands at one corner, outside some of the fancier shops in Khan Market, selling napkins and diyas.

He does not speak, much less beg a passer-by, and doesn’t whine about his ailments or hand out a booklet seeking money. He must hope that someone who has spent a few lakhs inside one of the fancy shops can afford to buy something small from him simply because it is economical, sustainable and of quality. That they would do so without bargaining. Tanvika always wonders how many have acknowledged him and genuinely spent time to ask him about his life instead of merely taking a photograph and uploading it on social media to prove they have contributed to society.

Charity is not about donating money at art auctions, at home decor stores or at fashion shows. One should invest time in ensuring that the benefits of one’s charity, or philanthropy, in fact reach the intended person. This should be done in a manner that preserves their dignity.

The person giving must also try and understand the person receiving, and support in a way that addresses their needs. Not just handing out biscuits and beverages but clothing, shelter, education, food and medication. These are their real requirements.

At a crossroads in Saket that we often drive by there is an elderly gentleman who also merely stands there, his hand shaking, perhaps due to Parkinson’s, selling roses. An elderly woman who sells incense sticks, after the loss of her son, competes for your attention. The old man stands in silence, waiting to be helped.

Rapidly developing urban India is full of such persons. Many think of them as ‘beggars’. They may just be ‘needy’, marginalized by society and the market. The organized philanthropy of business can address the larger social challenges a society faces. It is individual charity that must address the needs of the needy.

These are thoughts that cross one’s mind reading tributes to a ‘giver’ like Ratan Tata in the midst of a festival season. India is a nation of extreme inequality. There are the billionaires with their growing and aggressive opulence, and the desperately needy willing to wait in hope. Festival time is a period in which these social and economic inequalities stare us in the face, impact our ears and blind us to the reality around us.

Every cracker that bursts could have fed a family at least one meal. Yet, we pollute with impunity, air and noise, consume calories endlessly in celebration of our prosperity, unmindful of those who stand and serve. It is because of this deep-seated indifference to social inequality that Mahatma Gandhi enunciated the concept of Trusteeship. That a capitalist is a trustee of social wealth. The Tata Group under Ratan Tata’s leadership has come to epitomize this to a far greater extent than any other business enterprise. There are many business leaders who have undertaken profound acts of philanthropy and charity, Azim Premji being one of them. However, as a corporate entity the Tata Group has internalized this philosophy.

There is an apocryphal story on social media on Ratan Tata’s approach to trusteeship about a group ordering more food than they could consume at a restaurant. As they leave without having consumed all the food on the table, they are admonished for the wastage by a disapproving lady, “The money is yours, but the resources belong to society.” That was the essence of Gandhiji’s Trusteeship theory and Ratan Tata imbibed it more than most business leaders.

Sanjaya Baru is a writer and Distinguished Fellow at the United Service Institution of India

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!